Reviewed by Jennifer Lang

Days after the Israeli government restricted social gatherings to ten people or less and implemented social distancing, a masked FedEx man rang my door and handed me Disparates by Patrick Madden. The next day, when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared a national state of emergency, telling us not to leave home unless absolutely necessary, I brewed a cup of Earl Grey, sat on my balcony, and read. A new morning ritual: fifteen minutes, in the sun, to focus on words and the world gone quiet.

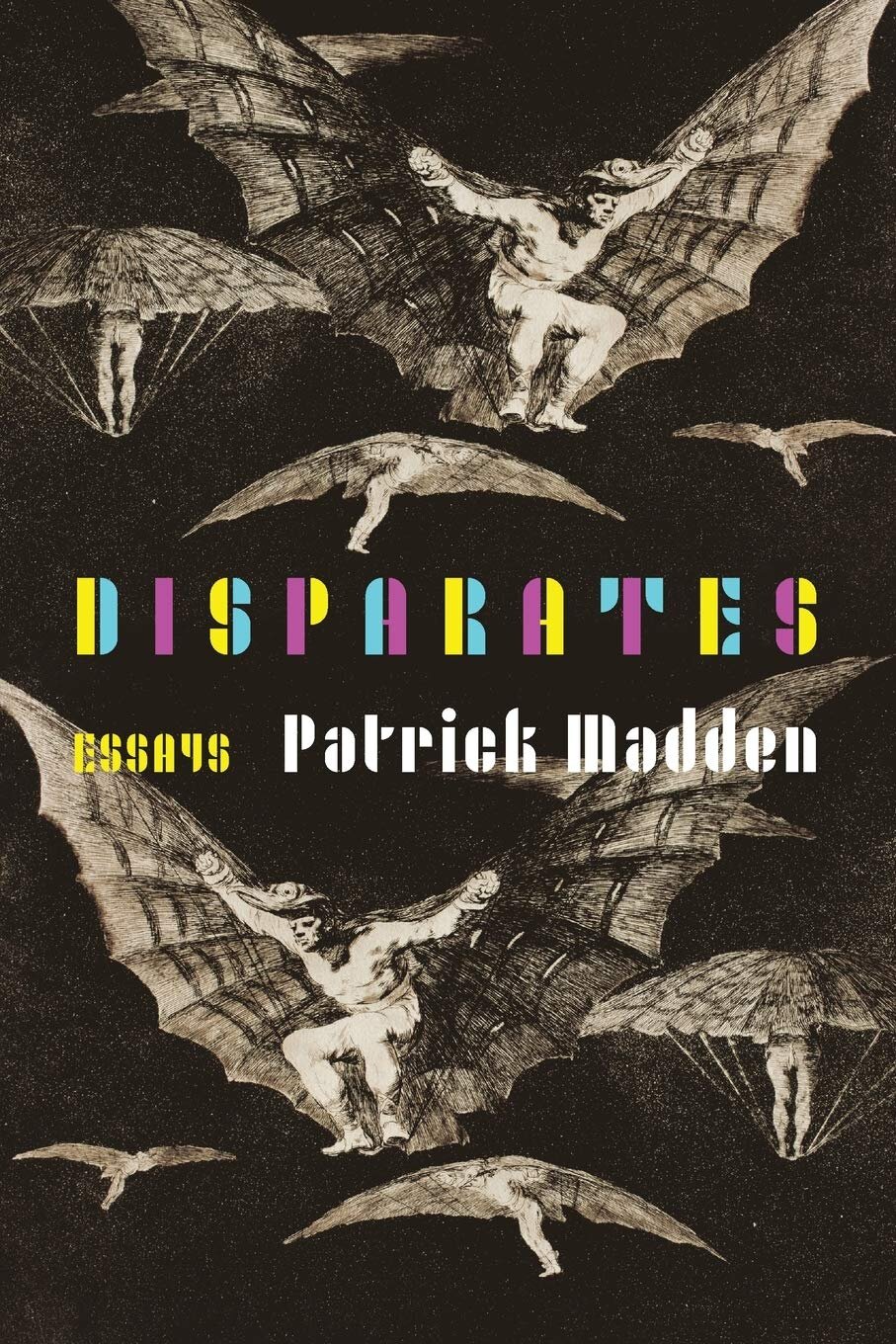

In his third book, essayist extraordinaire Patrick Madden entertains the reader with a combination of prose and poetry, hybrid and experimental writing, illustrations and photographs. The collection of thirty essays covers topics from fruit to fingers, grammar to emotion. And, like he did in his previous book, Sublime Physick, Madden invites friends and colleagues to contribute, proclaiming "all creation is arrangement, all originality is influences." We see the work of Lawrence Sutin, Elena Passarello, Michael Martone, Jericho Parms, and Joni Tevis, among others. Even his wife and children play a part. And music. Madden's music-dedicated past sings as he weaves lyrics and songs, referencing R.E.M., Rush, the Ramones, KISS, Pink Floyd, Steely Dan, Toad the Wet Sprocket, the Beatles, and Bob Seger.

Starting from the first essay, "Writer Michael Martone's Leftover Water: Imbibe literary genius (dozens of authors) in one swig!" I giggled. As the vibrant city of Tel Aviv came to a haunting halt, I laughed aloud at the farcical Q & A in which said writer Michael Martone auctions an 8.3-ounce bottle of Dasani water (plus backwash) left by Professor Michael Martone at Brigham Young University. The potential buyer and the water ask and answer twenty-one inane questions, such as: Does Martone floss? Are there any visible signs of Martone's interaction with the water bottle? What is the color of the water?

Madden approaches the Michel de Montaigne seriousness of essay writing with an edgy, intellectual lightness. It's as if he's challenging the reader to a duel to see who understands the pun, the reference, the metaphor, the words under the words. Like his French Renaissance predecessor, Madden ponders the big nouns like happiness, nostalgia, memory, and laughter. But that is perhaps where the commonalities end. Because Madden veers and dares and pushes boundaries.

Of the nontraditional essays, my favorite is "Repast," a five-page word-search story in one-word clues at the bottom about the title word itself: the act of eating. A structure freak, I looked at the letters and turned the page with wonder. How did he come up with this idea? How long did it take him? How did he make it work?

In the pages, we learn that Madden grew up Mormon in New Jersey in the 1970s and '80s, was a missionary in Uruguay, and that he speaks Spanish. He is married to a Uruguayan woman and they share inside jokes and play games with their children. He teaches writing at Brigham Young University. But the information is factual, pieces of the Patrick puzzle, just enough to personalize the essay but never tipping toward emotional-truth-telling memoir. He reveals but always keeps the reader at a distance.

In "Memorizing the Lyrics," he muses: "It feels, or I feel, ambiguous. Equivocal. Unclear. Disparate. Somewhat satisfied to have recovered a semblance of my untroubled youth, yet reaffirmed in my belief that I can never get it back. Too aware, too intentional, have I become."

The essence of this essay collection is transparency. Madden turns experiences and conversations and emotions and songs over and wrings them dry but admits he doesn't always know why he is thinking or recalling or sharing or writing or contemplating about them. Sometimes, he invites us into his mindframe and thinking process as if to break them down and share with the reader how he arrives at essaying. In part I of "Insomnia," when he is reflecting on last names (his wife's maiden name and his own), he writes, "Which is to say that you can essay about anything, find some small hook in the overlooked or takenforgranted." In part II, he takes the same two pages of text and uses erasure to tell the story of another woman in his life—his mother—and his meditation on home.

In "Order," he compares two genres: "Fiction writers can simply rearrange and embellish to craft the story they want. For a truth-teller essayist, this is not an option, unless the essayist indicates clearly the manipulations and perhaps offers them to the contemplative reader as fodder for a rumination on the nature of truth or reality or the essay genre."

While in "Plums," he writes, "this, friends, is an essay; a translation of memory into words and an attempt to find something of significance without preaching."

"Expectations" opens with a riddle he told his daughter to teach her about misdirection. In the second paragraph, he writes, "I came to feel that the best essay endings worked their way backwards through the text to shift a reader's understandings of the whole, to reconfigure interpretation from a new insight." Endings are my nemesis; I will think about this each time I start—and finish—an essay.

As Madden writes, disparate is an adjective meaning distinct in kind; essentially different; dissimilar. Morning after morning, as I read his work and watch busses and cars and the bakery beneath our building stop, I think it is the most apropos word not only to describe the collection of essays but also the current times.