Reviewed by John David Harding

In Empty Wardrobes, Dora Rosário finds herself in a precarious situation: her husband is dead, her young daughter is ill, and she has no life insurance proceeds or savings on which to survive. Her husband, Duarte, was a man of absolute, egocentric ideals. Duarte viewed ambition as a form of vanity; he, therefore, took no steps to improve himself or secure his family's future. "I'm not the kind of man who wants to rise in the world at the expense of others, or indeed of myself," he says. "I just let myself drift, that's all I can do and all I want to do." After Duarte's death, and because he had forbidden her to work, Dora must humiliate herself on a daily basis by begging for money from Duarte's boss, colleagues, and friends. She becomes a "career widow," an object of pity, and a pariah. One man mockingly refers to her as "Salvation Army" Dora.

For a time, members of the community financially support Dora and her daughter, Lisa, but this charity is not unconditional. Soon they claim that they can't afford to contribute very much, and their half-hearted promises to help Dora find work are never realized. While Dora and Lisa are not technically their responsibility, Dora feels bitter that no one, not even her well-off mother-in-law, Ana, will help her. Ana, a ruthless matriarch, despises Dora. To her mind, Dora did not help Duarte become the man he was meant to be, nor was there any evidence that Dora had tried to find a job while Duarte was alive. Ana's high expectations for Duarte are more stringently applied to Dora, who not only failed to be a good wife but also fails to be a good and scrupulous widow. The message is clear: Dora has only herself to blame for her misfortune.

At last, a friend puts Dora in touch with a man who needs someone, anyone, to manage the antiques store that he owns: "It could even be a woman, as long as she was energetic and totally reliable, of course." Although the job is unfulfilling, it affords Dora the chance to lead a life that does not revolve around Duarte. Lisa, on the other hand, dreams of becoming a stewardess. Carefree, she will jet around the world and enjoy the kind of life that Dora could only dream of. Like Duarte and Ana, Lisa acts and speaks without considering the consequences. "The only thing I believe in is life," Lisa says. "I know I'm going to be very happy, and I'll do anything I can to achieve that." Whereas Duarte expressed his egotism by martyring himself and coddling Dora, Lisa expresses hers by striving to become Dora's opposite: cosmopolitan, young, and free.

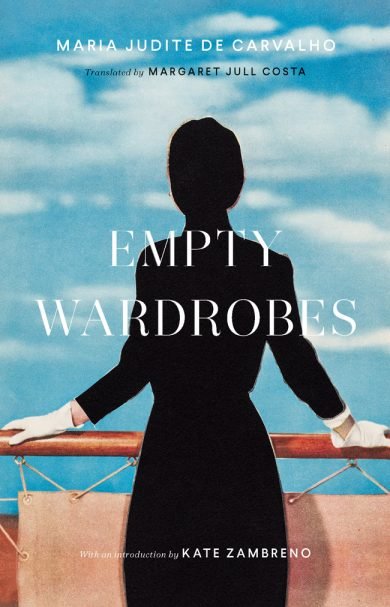

To describe the rest of this slim novel would be to ruin it. First published as Os armários vazios in 1966, Empty Wardrobes is the acclaimed Portuguese writer Maria Judite de Carvalho's only novel, though de Carvalho was also a journalist, painter, and prolific author of short stories. Translated from Portuguese by the award-winning and prolific translator Margaret Jull Costa, the novel is rendered in clear, finely-wrought prose. Not a single word feels wasted or misplaced.

The narrator herself is an acquaintance of Dora, someone with intimate knowledge of Dora's tribulations. Issues of narrative reliability are intermittently and poignantly addressed: "I'm not part of this story," the narrator says. "I'm a mere bit-part player of the kind that has not even a generic name, and never will have, not even in any subsequent stories, because we simply lack all dramatic vocation." But, of course, this self-effacement is a reflex; the narrator has been so conditioned to obfuscate herself (and her needs) that she tells someone else's story instead of her own. Early in the novel, she describes Dora: "She would sit quite still then, her face a blank, like someone poised on the edge of an ellipsis or standing hesitantly at the sea's edge in winter, and at such moments, all the light would go out of her eyes as if absorbed by a piece of blotting paper; for all I know, she may still be like that, because I never saw her again." This portrait no doubt achieves this level of clarity because the narrator closely identifies with Dora. Later, the narration clips along steadily, proceeding unencumbered toward a conclusion that is paradoxically predictable and shocking. This aspect reveals the novel's greatest achievement: its characters are so fully realized that their actions seem both inevitable and uncontrived.

This psychologically piercing novel lays bare the capriciousness of men, the betrayals they commit against women, the betrayals women commit against one another (and themselves) on behalf of men. Subtly rendered, these perfidies become all the more devastating when we assess their psychological wreckage. Dora and the narrator barely react (at least outwardly) to the blows dealt to them. Instead, they simply return to the "sea's edge in winter," a wasteland of grief and loneliness impossible to escape. Scholars of feminist writing and literary criticism will no doubt study Empty Wardrobes with great interest; fortunately, the novel is one of those rare, transcendent works that can be appreciated by a range of readers. Many people will see themselves in Dora, both the good and the bad, and may find some small comfort in knowing that even in moments of extreme alienation they are not alone.