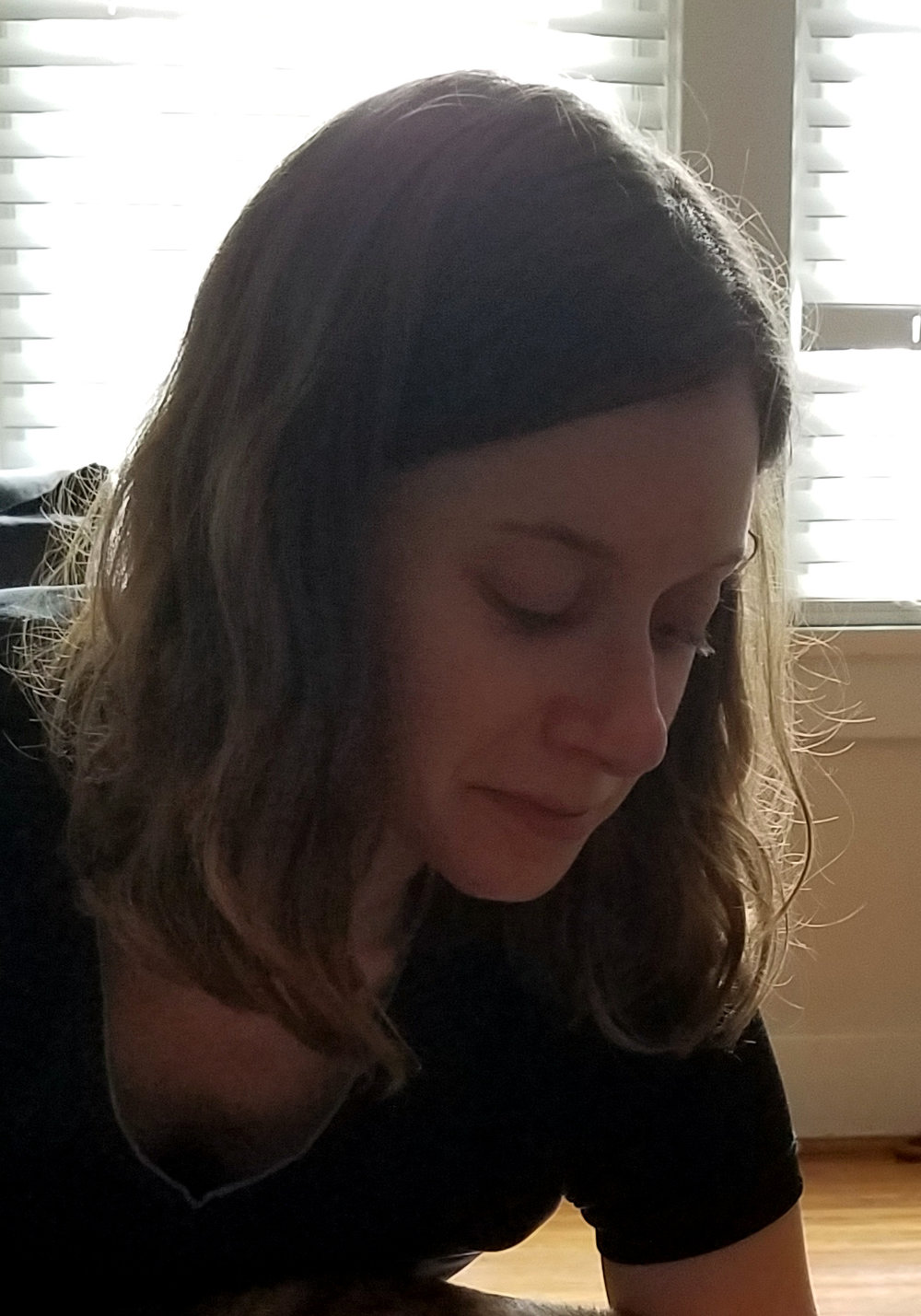

Jessica Newman currently lives in Louisville, Kentucky, where she is a doctoral candidate in rhetoric and composition. Along with other degrees from other places, she received her MFA from the University of Notre Dame. Recent work has appeared in the Denver Quarterly, Redivider, PANK, Caketrain and elsewhere.

Jessica Newman currently lives in Louisville, Kentucky, where she is a doctoral candidate in rhetoric and composition. Along with other degrees from other places, she received her MFA from the University of Notre Dame. Recent work has appeared in the Denver Quarterly, Redivider, PANK, Caketrain and elsewhere.

Her story, "The Doctors and the Very Tender Man," appeared in Issue Seventy-Nine of The Collagist.

Here, she speaks with interviewer Dana Diehl about beginning the writing process with a title, fairy tales, and perspective shifts.

How did “The Doctors and the Very Tender Man” begin for you?

The putting of pen to paper of this story began with a title—“The _______ and the Very Tender Man” —and I wrote the first paragraphs in an empty train on the long ride from Harlem into Brooklyn. These paragraphs expanded on what was already present in the title—the man’s tenderness—but it was not long before doctors and medication emerged, and I began to purposefully incorporate them into the plot and then into the title.

The content, or maybe the atmosphere, of the story began much earlier, with my own experience with medication, my own “strangest of weather.” Because the pieces that I write tend to unfold from a sentence or from scraps of phrases, the fact that “The Doctors and the Very Tender Man” developed from a title—an encapsulation of the piece—suggests to me that in this case my experience was particularly fundamental.

This story reads like a fairy tale. How do you think the conventions or restraints of fairy tales can shape the way we tell modern stories?

One of my favorite things about building off of fairy tales (whether retelling a particular tale or drawing on general fairy tale traditions) is that their conventions are ingrained in many readers. This allows the writer freedom to subvert those conventions and/or to use them to keep readers anchored as the writer experiments with other aspects of the text (such as using language in unexpected ways).

Halfway through the story, the focus shifts from the tender man to the woman who brings him groceries. Why was this shift important to the telling of the story?

The man is shaped by his physical relation with the world, particularly with people, with women. In my understanding of the man’s story, the most important development is not in his illness but in how he knows others. The story could only end, then, with a woman. The shift to the woman’s perspective was not a conscious choice, but rather one that made sense once it happened, and I see it having three major effects.

First, at the point of the perspective shift, the man is sunk in the time stretching out inside of him. He is background only and must remain that way for us as readers as the woman emerges. A shift to the woman’s perspective allows us to get to know her character while the man remains in his dark.

Also, the perspective shift allows us to better understand the man. We have so far been entrenched in him, inside hearing about his outside. The perspective shift allows us to see his surface, which has defined him, and to see things happening around him, to him.

Finally, the shift in perspective lets us experience how the woman feels about the man. The ending would fall differently if we did not see the tenderness that she feels toward him, the intimacy that comes from her seeing him bared.

If the first section of this story is the man’s, the second section is perhaps the woman’s, and the final section is them interlaced.

What are you reading these days that you’d like to recommend?

Right now, the majority of my reading revolves around my dissertation (which looks at the intersection of writing center studies, community engaged scholarship and listening studies) and teaching. This semester, I’m teaching a course on how women are represented in literature, and I’m excited to discuss Doug Rice’s Dream Memoirs of a Fabulist and Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, among other great texts.

I’m also looking forward to reading Calling a Wolf a Wolf, by Kaveh Akbar, after coming across his work in a recent Denver Quarterly. And I just ordered Laura Ellen Joyce’s The Luminol Reels. The excerpt I read in Sleepingfish promises a beautiful and violent morbidness.

Do you have any reading or writing related goals for 2018?

My overall reading and writing goal for the new year is to do a better job of carving out a mental space where I’m allowed to read and write something (anything) not primarily related to my dissertation. I’d also like to work toward having my doctoral work drive rather than drain my literary work, and vice versa. Specifically, I plan to return to and complete the book-length project that I’ve been working on for some time.