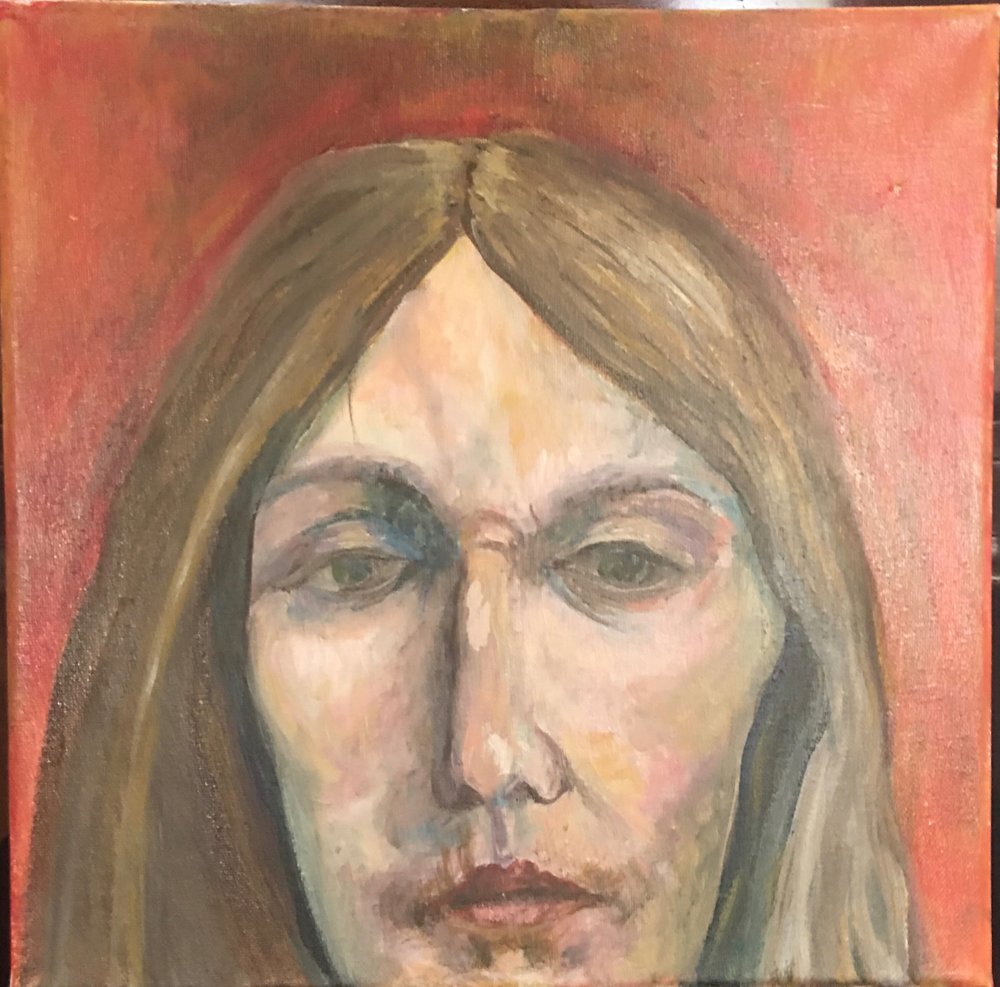

Karen Brennan is the author of seven books, the most recent of which is a hybrid short fiction collection, Monsters. Her poetry, nonfiction and fiction have been included in anthologies from Norton, Penguin, Graywolf, Michigan, Georgia and others. A visual artist as well as a writer, she is currently at work on a compendium of image-word memoirs, Television. Professor Emerita at the University of Utah, she is on the faculty of the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers and is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

Karen Brennan is the author of seven books, the most recent of which is a hybrid short fiction collection, Monsters. Her poetry, nonfiction and fiction have been included in anthologies from Norton, Penguin, Graywolf, Michigan, Georgia and others. A visual artist as well as a writer, she is currently at work on a compendium of image-word memoirs, Television. Professor Emerita at the University of Utah, she is on the faculty of the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers and is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

Her essays, "C'est moi," "Shame," and "Gurus," appeared in Issue Ninety-Seven of The Collagist.

Here, Karen Brennan talks with interviewer William Hoffacker about short forms, memory in fragments, and indelible marks.

Please tell us about the origins of these three micro-memoirs. What inspired you to start writing them?

These pieces are part of a longer project, titled Television. I’d been looking for a vehicle for memoir, other than a chronological narrative. Memory is so often fragmentary and so the stories of our lives come to us in pieces, in glimpses. The final product, book-length, is an assemblage of memories, arranged to mimic the way the mind flits haphazardly from topic to topic, era to era in the act of recollecting a life while in the midst of living this one.

Each piece consists of only about 200 words or fewer. What has drawn you to such a short form? How much of a challenge is it to write a complete work so concisely?

As a poet as well as a prose writer, I am drawn to the short form. It is a matter of compression and release or, as E.M. Forster said of plot, “a system of tension and resolution.” On the micro-level, the process is speeded up, the rhythms are especially crucial and resolution is less ending than opening.

In the third piece, “Gurus,” you describe the sort of scene that used to take place in a particular room you were once in more than you show the reader what was actually taking place while you were there. Why do you believe the history of that place pulled your attention? What’s the significance for you of that space’s legacy (or any given place’s storied past, perhaps)?

Well, it’s ironic, for one thing. The idea that the place where we worshipped a spiritual leader on a throne used to be the venue for Borscht Belt comedians is pretty hilarious. But, really, this piece is about imagination—how the narrator imagines what must have been there before and wonders about the layers of history that inhabit—and possibly affect—a particular space. I used to live in an old Victorian, circa 1996. There was writing on the inside of one of the closets left by the wife of a well-known poet in the 50s, a stove from the 1920s and an apricot tree over 100 years old. It all struck me as magical, as if I were destined to be there and to leave some kind of indelible mark.

What writing project(s) are you working on now?

Mainly the book I’m calling Television.

But also a play and some poems.

What have you read recently that you want to recommend?

Murakami’s marvelous new book of short stories; Robert Musil’s Posthumous Papers of a Living Author; HHhH by Laurent Binet; Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful: a book about jazz.