Reviewed by Alyssa Witbeck Alexander

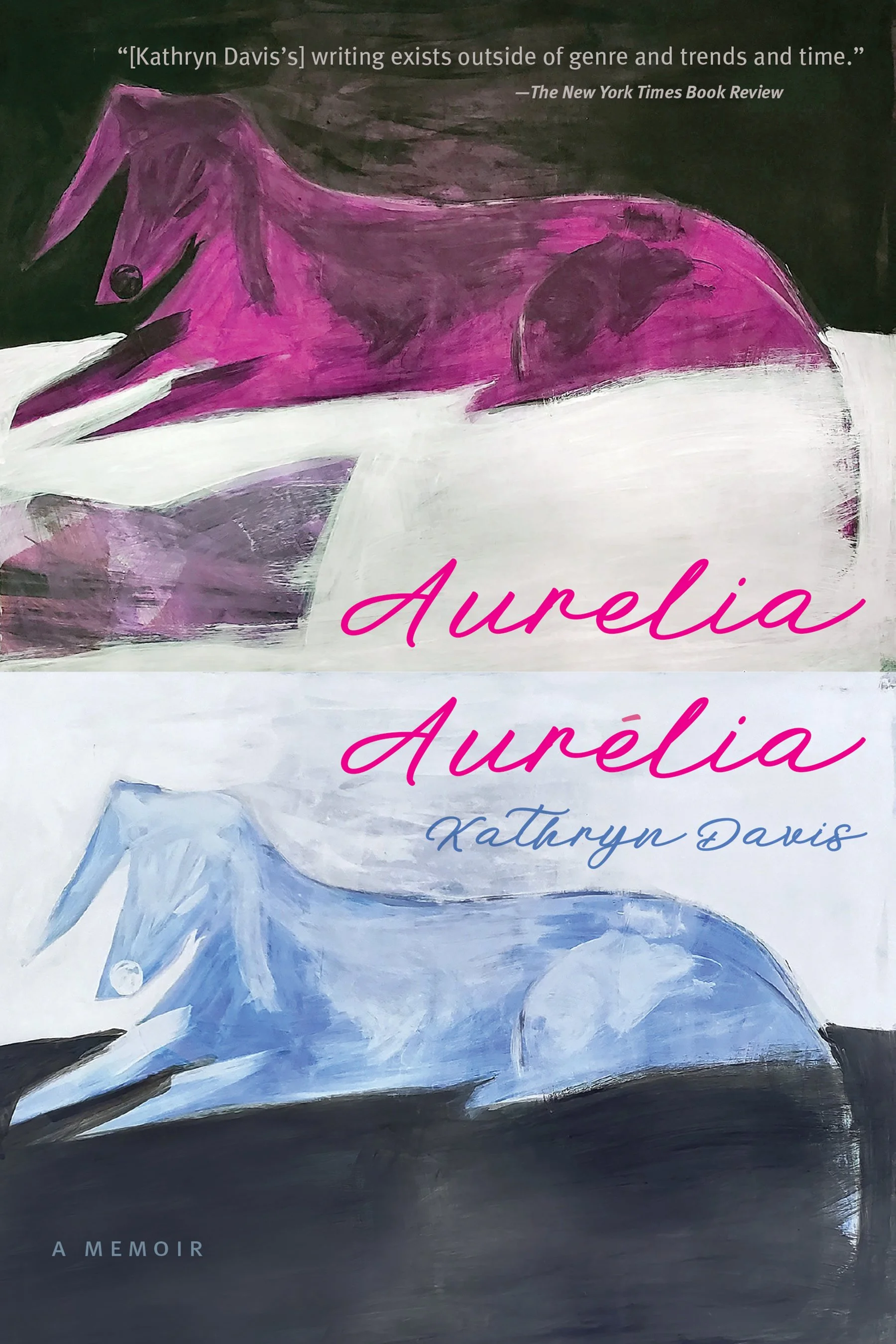

Eight-time novelist Kathryn Davis catapults into long-form nonfiction with Aurelia, Aurélia a memoir that centers on her husband Eric's death. However, even more than his death, Davis writes about his dying.

Liminal spaces—the crossing from one place to another—haunt this brief but moving memoir. Davis begins the book with a crossing, traveling the ocean on a student ship, the Aurelia, then blends the narrative into a meditation on To the Lighthouse. Reflecting on her childhood, Davis recounts that she "wanted to be Virginia Woolf," to write into the movement as Woolf. Davis points out, "there's no such thing as transition without there being a point of departure or a point of arrival." The point of arrival for Woolf's characters is the lighthouse; the point of arrival for Davis is Eric's death. However, Woolf's book isn't about arriving at the lighthouse, just as this memoir isn't about the arrival of death: "We're in the place of transition, the point of intersection between the rook in Virginia's brain and the rook in ours."

Eric is dying of cancer and has an unknown amount of time left to live. He put a lot of work into the home that he and Davis share together, and he is sad to leave it. "But you don't have to leave the house, I said. You could haunt it." And so, Davis haunts this memoir with the idea of haunting. She returns again and again to ghosts through chapter titles ("The Haunted Tent," "Ghost Story One," and "Ghost Story Two") and quick references to otherworldly hauntings.

Just as a crossing begins with departure, "a ghost can't just rise up out of nothing." Davis meditates on bodies, how Eric ended up in his, how their daughter ended up in hers. We live in our bodies, expecting a lifetime to last nearly forever, and assume that the people around us will live long lives too. "And then?" Davis asks. And then the haunting. After his death, Eric haunts Davis when she smells his cologne on his books or pictures his face. Though "you can only be haunted if you believe in an Other." If a person doesn't believe in an existence outside of this one, they can't be haunted by it. Eric haunts Lucy, their dog, who loved Eric more than Davis. Lucy sporadically runs the length between two signposts, as if searching for something. Or perhaps, finding Eric.

Ghosts, or maybe any idea of an afterlife, break the rules of transition. After all, "once you died you had no choice but to go on forever and ever." Davis describes dying as a set of doors that a person is unable to walk through but that still go on eternally. Door after door after door with no arrival.

Davis's writing is described as "dream-like," though beyond that, her memoir is ghostly. Writers haunt their texts after they're written when readers peek into the mind of the artist. "And there you are," she writes, "ghostly you and the ghostly artist, in ghostly communion in that nonexistent place between words, images, notes." As readers, we interact with Davis at her time of writing; we witness her relationship with both readers and grief on the page. Books live—or exist—in that in-between.

Davis writes into her journey of becoming a writer, a process that was not passive. At one point, "there was no distinction in me between reader and writer. I was, in every fiber of my being, both, simultaneously; I was becoming an artist." Falling in love with reading, and subsequently writing, was electric for Davis. Even after writing eight novels, she can "feel a ghost of that first ecstatic shiver" of when she read Hans Christian Andersen and almost believed the stories were her own. Davis brought Andersen's stories into herself, like when she wanted to be Virginia Woolf. The creation and consumption of art haunts writer and reader, doors that go on forever.

The story goes that, moments before Beethoven's death, he raised "his fist to the heavens to curse the gods," after which there was a clap of thunder and he died. Davis quotes Beethoven saying, "Art demands of us that we do not stand still." In this way, creating art is a crossing on its own—perhaps even a haunting for artists compelled to create something outside of themselves. Davis writes of how she wanted to be great in the way that Beethoven is great. Perhaps part of that greatness is our art existing beyond ourselves. We return to Beethoven's music over and over; we haunt the creations of a dead artist.

In this memoir, Davis bends conventional rules of nonfiction. The "Ghost Story" chapters blur the lines between fiction and nonfiction, between lived experiences and emotional truth. While on a train, Davis meets a woman: "I thought maybe I recognized her—from life, which was what this didn't seem to be." As a reader, I don't know which parts of the story happened in Davis's life. The ghostly scene of her careening while on a train or in a van may not reveal fact. Instead, they open into a truth of not knowing where one is—this inability to find a place speaks to a loss of certainty in the story, in grief, in life without Eric. Maybe to reach the emotional truth of grief and art, we need a place in between fact and fiction. Davis uses both ghost stories and memory to pay a tribute that neither can do on its own.

Love brings people on an emotional journey, crossing from one state of mind to another, and possibly to insanity. Aurélia is a novella written by Gérard de Nerval, a novella that explores "romantic obsession taken to the point of madness." As opposed to the figurative movement of falling in love, passengers on the Aurelia cross the ocean literally. Though much of Davis's life has included mental and physical forms of crossing, grief encapsulates both. A loss of a body, a loss of a mind.

As a reader, I was anchored in Aurelia, Aurélia. The first page hooked me and didn't let go for 128 pages. The poetic language and associative moves between topics and ideas pulled me into the throes of grief and art, of haunting and transition.

Davis remembers Eric saying, on his deathbed, "That's all you get, a ripple, a little bitty thing, a wave." Eric's life existed like a wave—there for a moment, and then gone. Perhaps when Davis watches ocean waves, arriving then disappearing, always moving, she thinks about the previous waves. The ones that used to exist but disappeared into the ocean, haunting it.