Reviewed by Geri Lipschultz

The only thing crueler than a mother losing a child is the child losing her mother—which turns out to be the subtext, the inspiration of Barbara Henning's book Ferne: A Detroit Story. The book is not billed as a memoir—although there are moments in which Henning honors that aspect, such as in the introduction when she writes: "I kept trying to find her in my dreams and memories, to become like her, perhaps to even become her. Her old stockings with black seams and runs were in the drawer in my father's room. I took them upstairs to my room; they still smelled like her."

It's there, though, the feeling of memoir, in between the words; it's the spirit of this "novelized" biography of the woman she wants to know as "Ferne." While she alludes to it, what Henning does not do here is mine the depths of her loss. Rather, she imparts a full vision of the woman she has mourned for half a century, the mother who died when she was just eleven years old. The breeze through those years of her mother's brief life is thrilling for its specificity, for Henning's attention to both the vagaries of the extended family and the national—and yes, international—history that insinuates itself into their lives. With Henning, the reader threads through the thirty-eight years of Ferne's life in Detroit, Michigan, a familial history that touches on the lives of Henning's great grandparents in France and Switzerland—and ends with her mother's last breath.

Long before she had established herself as a poet, essayist, and novelist, Henning began the research for this book. One could say that it was a time when memoir held more legitimacy for those of celebrity status. She writes about encountering resistance while interviewing her aunts (Ferne had seven siblings) for an assignment in a college women's studies class, receiving discouraging responses: "You are raising the dead," "Let her rest in peace," and "She never did anything famous."

Here, she rhetorically asks: "Why tell stories and imagine the life of my rather ordinary long-gone mother? Because I am still in love with her . . . a woman who lived in a transformative time: born when women first got the vote, a child during Prohibition and the Great Depression, then coming into her young adult life as World War II changed everything."

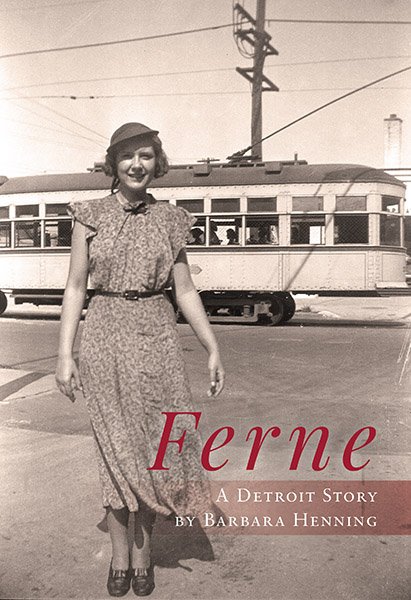

Decades later, upon the death of her father, Henning's family gave her a set of albums, the so-called Snaps books with photographs and documentation obsessively assembled by Ferne, herself—photographs that Henning had pored through as a child but her father had "locked away" when Ferne died. In one of the albums, Henning finds a photograph with "the notation 'Times paper boys'" alluding to her grandparents' having rented garage space to The Detroit Times. Henning's own father had been a paper boy, picking up his papers from her grandfather's garage. These and many more moments of synchronicity provide fodder for this very unusual book concept come to life. Concerning that very last part of Henning's justification for a book that offers an account of someone who was "not famous," Henning also has at her disposal a copy of her maternal uncle's documents regarding his experience as a prisoner of war in Germany. This is a book that turns out to be large in scope: a book that reminds us that there is a world within every human being.

Henning has done more than just the family research, offering numerous citations that tether Ferne's story to the larger picture, which at first reading feels a little like rock hopping. This is not a narrative to sink your teeth into. It resembles a scrapbook, with its faded photographs from Ferne's collection, quotations from letters, along with the images of both full and partial articles from The Detroit Times and two other newspapers. These elements are like stars, constellations, to establish context. It may not be an easy beginning, but if the reader persists, if she can negotiate the terrain long enough to feel the tight familial bonds of the extended family—along with some real, striking images marking the time, showing us just how far we've come in terms of feminism and even humanism—the rewards are worth it.

You find yourself invested in Ferne—first as child, as young girl, as a young woman eager to marry (whose first and second husbands don't exactly fit the bill). Then as a wife and young mother whose loyalty to her family comes from the family itself—Ferne was the second youngest of what was once nine children, where the older children cared for the younger, and where childbirth occurred in the home itself. You also find yourself invested in the gone world that was hers as it comes to life. The approach is kinesthetic, it's chancy, but the reader willingly feels compelled to jump from one document to another, working to understand a world that for this reader was also my mother's world. We see Ferne's stance on "white flight," lest we forget the racism that came to be in Detroit, not to mention the classism that exists wherever humans seem to be. Not only do we see her as part of this microcosm, but we see her insistent on smoking those cigarettes that will keep you trim, or, better yet, from an ad Henning includes: "'Light a Lucky and you'll never miss sweets that make you fat.'" While Henning offers us clips of women forced to do their "patriotic duty" by quitting their jobs for the sake of the unemployed men, Ferne herself gives up her job to be with her husband while in boot camp—and later to have children. Ever resourceful, Ferne brings in money by sewing for her neighbors. We see her defying the doctor's warning to stop having children because of the damage to her heart. And by the end, we see, by way of another coincidence, just how much Ferne's loss meant to Henning's father.

One recalls Henning's statement early on, in the introduction itself: "When I gave birth to my daughter . . . I was my mother giving birth to me . . . When I was 38 years old, and her death date passed, I was surprised that I was still alive.”

The work is billed as a "novelized" biography—which I imagine is due to the dramatization of events that might not have happened exactly as written, but I think of it as biographical memoir—because the writer speaks of her own story, as well. So, it's not solely a biography of her mother—and it's that intersection that draws in the reader.

Ferne's death occurs at a time when the state of the art of the heart is such that cardiology itself was in its infancy. She would have survived had doctors known how to replace a valve—she'd had rheumatic fever as a child, she'd smoked, and she was determined to have four kids because having two was just not enough to constitute a family in her mind's eye.

And with the writer, you mourn her by the end, even though you knew from the very beginning that you, like Henning, would lose her too soon.