Reviewed by Joe Sacksteder

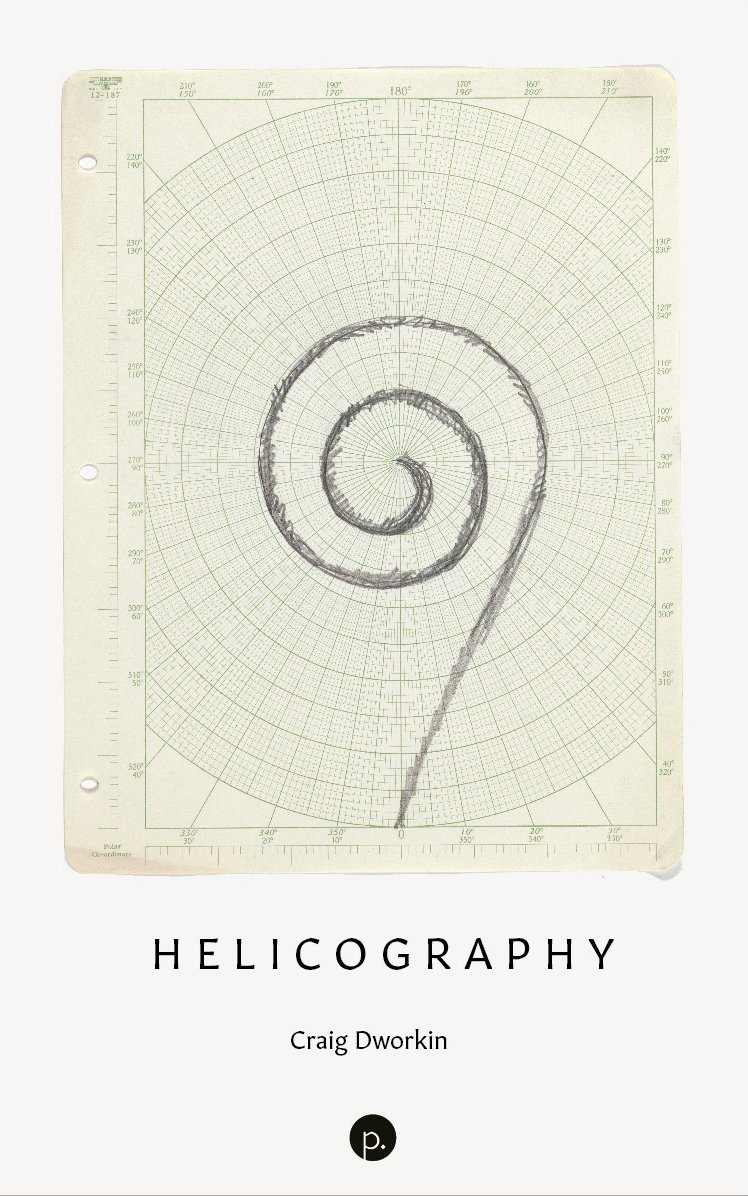

Theories of Forgetting, a 2014 novel about Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty by Craig Dworkin's colleague at the University of Utah, Lance Olsen, achieves a sense of spiraling in part through its pages' multiplicity of reading paths; attempting to navigate two narratives—one running beginning to end, the other end to beginning, upside-down—causes one to continuously rotate the book 180°. Dworkin's new book from punctum books—"part art history essay, part experimental fiction, part theoretical manifesto on the politics of equivalence"—achieves its spiraling via scalar play, expansion and compression of time and space, and nonstop associative leaps on a line and sectional level.

I was thinking of André Breton's Mad Love long before Dworkin quotes the "éloge du cristal" in the postface, the way the text modulates through a succession of images over the course of a hundred pages: train abandoned in a jungle—crystal—coral—mask—spoon—slipper—bullfighting—cactus milk—black sand—lava—sempervivum—mangroves. Dworkin, too, begins with a train, kicking off his scalar play and launching a similar succession by turning the First Transcontinental into a giant watch spring, noting "Were it scaled to the extension of Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty, [it] would stand as a 1.625-meter-high wall, half a foot thick, extending from the bridal of the shore to an arbor around which the final turn of its coquillonage curves, to reach 1,466.75 meters, weighing over three million kilograms." From there, very approximately: snails—birds—snakes and their rattles—the Bingham Canyon Mine (just to the west of Salt Lake City)—Chris Marker's film La jetée—Alfred Jarry's King Ubu (and the spiral on his torso)—the Guggenheim Museum—extinct sharks and their teeth—"jetty" / "projector"—Hitchcock's Vertigo—dust—helixes in nature—"pier"—products and byproducts (oil, tobacco, milk, sugar, water, shit, saliva, sweat)—ferns—the Great Salt Lake's mythic outlet / whirlpool—phonograph discs—classical music—labor and wages—"spindle"—evolution and orthostatism—the inner ear. Dworkin's movement among these subjects, many of them already involving spirals, is less of a linear trajectory than Breton's, often returning in particular to the mine, the museum, and King Ubu, as they circle around the Great Salt Lake, Smithson's earthwork, and Howard Stansbury, who surveyed the area from 1849-51. The book begins in Stansbury's thoughts and ends by transitioning readers back to Stansbury by way of a quick hurricane-to-cochlea leap: "the pattern of the churning vortex, for a split second, perfectly matched the spiral of his inner ear in a silent alignment of form within form." Stansbury's bookending of Helicography is just about all that readers clinging to traditional notions of the genre can point to in order to justify calling this a novel, which Dworkin sometimes does.

Readers are primed for auguring deliberate intentionality into these movements and nested spirals by Smithson's Spiral Jetty film, in which viewers will at some point begin to relate the land art's shape to the spinning of the blades of the helicopter from which so much aerial footage was shot, then finally—via the spools of film seen on a desk—to the very medium of the film itself, which had been rotating inconspicuously the whole time. Connecting the etymology of jetty and projector leads to one of Helicography's lyrical flights that stands out in particular because of the book's general denseness and opacity. Having imagined the Bingham Canyon Mine shrunken down to the size of Spiral Jetty, Dworkin translates mass to temporality: "Each year the silver from a Jetty mine would be sufficient to manufacture four hundred prints of Marker's La jetée, or three hundred fifty prints of Smithson's Spiral Jetty film, or thirty-five copies of Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo." (Dworkin does not go into how Marker's films spiral around his obsession with Vertigo, an Easter egg for those in the know.) "Every screening illuminates the image of its death," notes Dworkin to describe the degradation of celluloid. "Any given print survives only a few hundred runs through the ravenous chewing of the apparatus, and so any single cinematic image survives for only one and one-third seconds before it disappears, unviewable as motion picture ever again." Such alchemy is a distinctive feature of a book that Dworkin claims is the exact length read aloud as the drive from his house to Spiral Jetty. The descriptions of the mine and the Guggenheim—in whose distinctive shape Dworkin sees "a mirrored displacement of the mine"—are places where these lyrical flights are at their most defamiliarizing: "The mine sinks, by steps, like an inverted ziggurat . . . a temple to negative space. The razing by its tracked pneumatic priests enshrines a geometry of absence. It measures the earth with its own displacement . . . an amphitheater for viewing its own tragedy."

Helicography bears notable similarities to Christian Bök's poem "Alpha Helix" from The Xenotext, Book 1, which Bök describes as "a delirious catalogue, listing 'manifestations' of helical imagery in the world, testifying to the ubiquity of living poetic forms by imbuing everything with the proteomic structure of life." Likewise to Bök's Eunoia—in that it can be seen as including the common subjects that each of Bök's lipogramatic chapters share ("a culinary banquet, a prurient debauch, a pastoral tableau and a nautical voyage"), in that it revels in heavily-accented wordplay, for example "archaic alcaics tide tides" and "the line from avis to avis, 'warning' to 'bird,' a visagra for a whisper, a visage for a whist, the rese before arrest," and in that its author surprisingly surfaces at times to offer commentary, for example "(Incredible, considering the tremble, to think that aspen, collapsing, ouroboric, the flutter of its leaves like a silent rattle and their shape like the head of a snake, teethed at its extremities, is etymologically unrelated to asp.)" That local area in fact, just over a page, is dotted with "aspiration," "asp," "aspen," "diasporic," "aspect," "asphaltic," "asperity," "aspherical," and "asphyxiating" (and "gasp" and "collapsing" and "wasps" and "exasperated" and "blasphemous" and "unclasp" and "jasper").

As the helicograph is an instrument that helps one draw spirals, Helicography is an accurate label for a book that it would be modest to sum up as "writing about helixes." This title prepares readers for one of its most immediately apparent surface features: it contains a lot of obscure words. On page 116, for example: "halophiles," "glume," "scaberulous," "acuminate," "scarious," "crithomancy," "glabrous," "coriaceous," "lemmas," "suborbicular," "obvoid," "retuse," "apically," "perianth," "achenes," "adumbrate," "fimbriate," "sepals," "laneolate," "sporocarps," "biscoctiform," and "tarn." Rather than the goal being to impress readers or obfuscate meaning, this feature transfers the text's scalar play to the realm of language, showing its vastness beyond the relatively limited fraction of words we use to get by as creatures. Looking up the unknown words will confront readers with etymology, adding a diachronic dimension to readers' reeling, as well as potentially with the limits of Google's seemingly divine algorithm and the internet's representation of our species' collective knowledge.

Readers will find themselves feeling what affect theorist Sianne Ngai termed stuplimity, the syncretism of shock and exhaustion that accompanies "thick" texts of modernism and postmodernism like Gertrude Stein's The Making of Americans. Unlike the sublime, which hits us in one overpowering moment in time, we confront the stuplime again and again as we press through the mud of a text, pulling us down into its language. The effect is similar if readers engage with the citations, the "Quotations, Allusions, and Deformations" that comprise a full 60 pages, sources Dworkin culled for often single, inconspicuous factoids (for example the amount of defecation produced in Lafayette County, Arkansas, in 1894, from Dr. Chase's Home Adviser and Every Day Reference Book), many of which are obscure, centuries-old, and specialized / vocational. To do so is to encounter the weight of our species' textual production, the existence of humans shitting in Lafayette County in 1894 and someone writing it down, and the gargantuan task of Dworkin himself unearthing each text, choosing such details in the history of humanity to breathe strange new life into for such seemingly arbitrary and passing payoff. Over and over and over again.

The preservation of such sources and accounts paradoxically underscores their obsolescence, which is appropriate given Spiral Jetty's entropic concerns. Even as I read about a transaction between a J. Cameron and a G. Knight in 1850, as related in an informational book on single and double-entry bookkeeping by William Inglis, I understand that I might be among the very last humans to do so, that my interaction with these long-dead figures is slight and predicated largely on happenstance, and that countless other such accounts are lost forever.

Included in Helicography's engagement with other sources are many instances of textual appropriation, both short and long; most surprising is how what appears to be the author surfacing most dramatically and extensively in the final pages to state an unexpected moral of the story is in fact two full paragraphs of appropriation, one from Edgar Allan Poe's essay Eureka, the other from César Aira's novella Artforum: "The conclusion I hoped to reach with this story, with this series of caprices and tocades, was the following: the most dissimilar facts can be connected in such a way that they participate in the same narrative, and their incoherence can become coherent." This type of coherence is akin to Sianne Ngai pressing on Fredric Jameson's critique of "schizophrenic" postmodernism as inevitably resulting in "heaps of fragments," noting that "insofar as 'to cohere' means 'to hold together firmly as parts of the same mass; broadly: STICK, ADHERE,' a heap does seem to be a coherence of some sort." And it's akin to Smithson's own 1966 A Heap of Language, which explores language's capacities for concrete materiality.

In Helicography, Dworkin's heap of language evokes Smithson's heap of basalt in a way that allows readers to dwell in the dizzyingly expansive space between the "stone" and its projection beyond language, beyond representability, in Viktor Shklovsky's famous charge that art exists to "make the stone stony." In perhaps its most stunning passage, which begins by imagining Spiral Jetty played like a record, Dworkin goes further to wonder "What variety of lines, occurring anywhere, could not be put under the needle and sounded?" Helicography comes as close as any text might to such a daring and impossible dream.