Reviewed by Sarah D’Stair

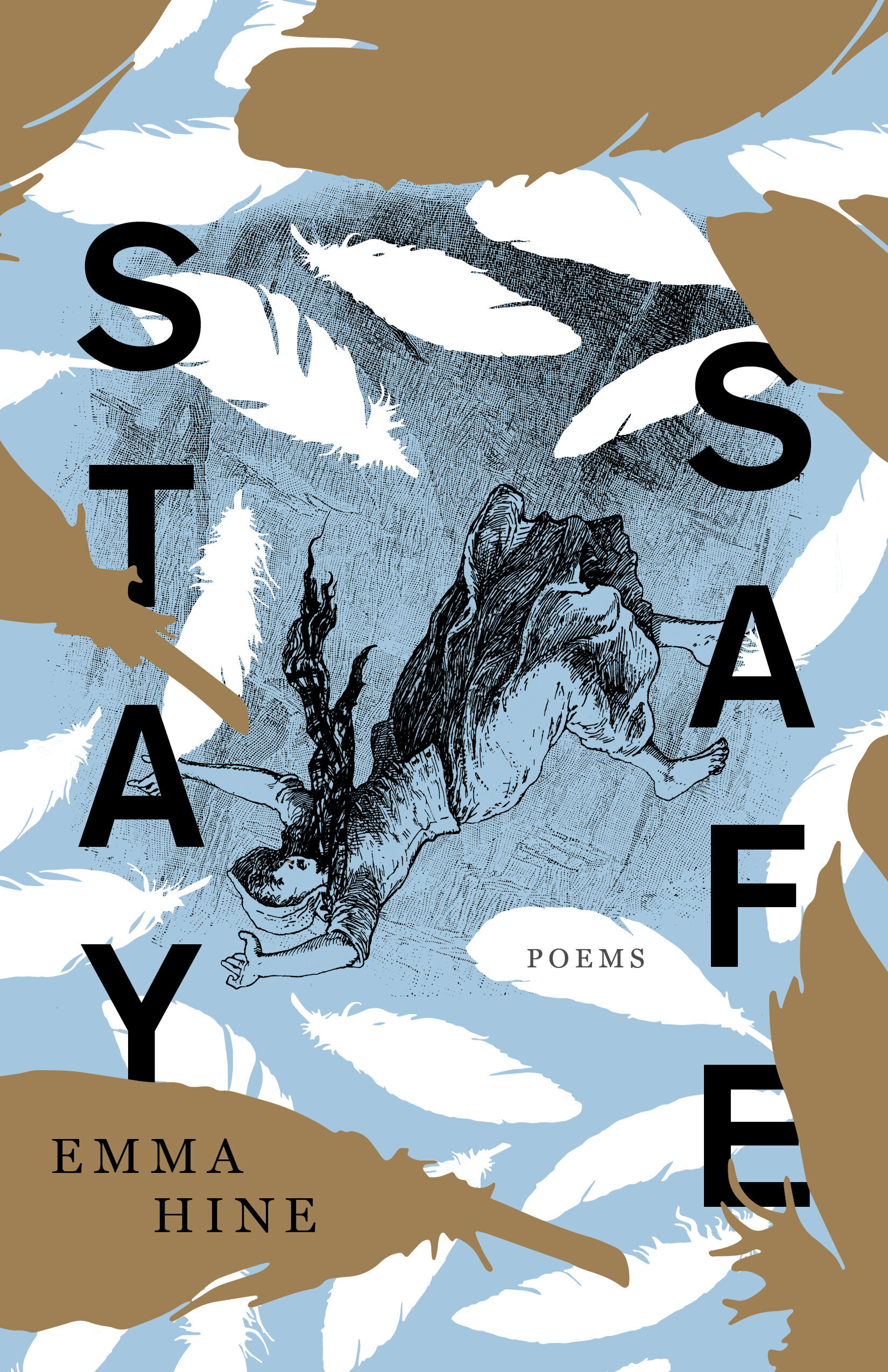

We all know a mythmaker—a grandfather who tells old stories, a gossiping workmate, a politician, or a religious leader whose sermons uplift you. Maybe it's that one friend who takes endless photos, catalysts for later reminiscence, or a sibling who keeps all the family secrets. We all know one, but Emma Hine's Stay Safe reminds us that for the fortunate, that someone, that keeper of myths, is a poet.

The collection is a melancholic reverie of sisterhood, chronicling myriad moments that define attachments—those forged not only by blood and proximity but also by a shared sense that only togetherness will mediate inevitable ravages of change and loss. The speaker grapples with the family's repeated displacements, their mother's severe illness, a friend's suicide, wartime death, initiations into the sexualized body, and many other fraught, identity-shaping experiences both public and private.

These moments, captured in pristine, elegant verse, coalesce into an accumulated trauma mediated only by the poet's ability to shape, re-construct, and render into myth their emotional import. Yet the collection is less about the stories themselves, less even about the way the speaker crafts them into symbol and word. Rather, Hine's more acute interest is in the impact the process has on the mythmaker herself. It's the burden of the enterprise along with its complicated joy. It's the psychic danger inherent in the distance the process requires but also the safety that distance provides.

Early poems make sense of an uncontrolled, unstable world by transfiguring bodies into otherworldly creatures that are not bound by linearity or spatial definition. In "Selkie," the poet turns the sick mother into a seal who lost her pelt while on land, only ceasing her search for it out of love for the children she bore. In "A Circling," great-uncle Frank, bitten by a shark, becomes the "scar" on the disfigured family body, an omniscient presence the speaker cannot regard directly but also cannot stop from seeing. And in "Don't You See," an undefined tale of lost children evolves in the telling; it mirrors memory, which naturally distorts raw truth:

Sometimes when I tell it they fall

and their parents find them twitching

like wrens on the flagstones, grieving

over wings that didn't work. Oh well.

In other versions the children do better . . .

These and other poems establish the speaker as the teller of tales, the crafter of truth into myth. Other poems, however, telescope out from the family to imagine the symbolic resonance of the storytelling process. "Red Planet" is a kind of daydream about how Mars must feel when the many ricocheted probes come just so close only to be catapulted away: "she so loves the probes. When they land, / she goes as still as she can, so they won't startle / and unlatch." This poem, to me, seems to be a metaphor for the speaker herself, the one who internalizes experience then radiates it out as crafted truth: unreachable, "bolted in place," yet longing for closeness and integration.

As we consider how art mediates life, the poem "Hotel Sisters" brings pop culture images into the equation. During a long drive, the sisters "take turns scrying the dial / for a clear tune to dance to"—that word, "scrying," is what makes Hine's poems so compelling. That one simple act of turning the radio dial becomes an act of foretelling; the sisters are now the Fates, vying for control over "the bargains // of the universe on loop / in the static and grind." The speaker then imagines the car "overturned // on the road, one wheel / still spinning" while the radio pop song continues its wail over the wreck. Such mythic certainty in that iconic image. Such terror too.

One of my favorite poems in the collection is "Still Life," which follows a goat as he roams through the halls of an abandoned art museum. The concept is brilliant: a goat, remarkably unconcerned, almost awkward in its meandering, exists in tension with art, which is hallowed, elegant, deeply concerned. The speaker again becomes fabulist here, in language reminiscent of a children's animal story. We note the repetition of the word "it" so that even the vital living body becomes an object of art:

It walked scratchy and brown

through the wide galleries and the long empty halls. It got cold. It

turned its back on the quiet ballerina and breathed along with the

saints. It blinked with horizontal pupils at its own reflection in the

marble floor but did not know itself and walked across the glassy

yellow eyes. In one hall there was a painting of a goat hanged with

a rope. The soft V of its neck strained against the canvas.

We are invited to see the goat as the healthy observer, regulated in response and measured. After all, just because we revere images doesn't mean they merit reverence. Or perhaps we see the goat allegorically, as no different than ourselves. We, too, encounter images of violence every day, and with calm assurance, walk away.

Later poems in the collection consider not what mythmakers do to the past but rather what happens when they are confronted with the future. How does one mythologize what has not yet been, except by daydream? What do hypothetical possibilities become if not confrontations with flailing reality? Like the retired racehorse in "This Time," we break our necks bolting toward a future we do not understand, "running like it was the only way / he knew to be in the world—whinnying, bucking, tossing his head." The future's ethereal grooves, its unspoken harshness, its messy web of unknowns is symbolized by the soccer net the horse finally falls into, "tangled, / breathing so hard the mesh rose and fell with his ribs." Yet without this thrashing, we fall into the future of the poem "Spell," where all is well at the end—the woman survives the fiery crash, the trees survive the blight—but somehow what is expressed is a hope rather than a truth.

In a short essay titled "On George Oppen," Louise Glück reminds us that "precision is not the opposite of mystery." Hine's language embodies this sentiment. It is pristine poetry: no word out of place, no roving comma, no ill-conceived image, no lines running wild off the beaten path. It's almost painful in its precision, like a deep wound caused by the sharp edge of a knife.

"Flight Path," a long rumination on the death of the speaker's grandfather, describes the sisters' trek out to a beach "to scare the ghost crabs, which drown / in water and suffocate in air." This is a deeply true image. The two states—desperate survival and vigorous aliveness—become indistinguishable, illustrating the basic conundrum of the storyteller. To pull others into our versions of truth, we must perpetually detach. To stay relevant, we must skirt the line between life and not-life. That is the space where Hine's poetry lives. And in this way, the title Stay Safe becomes an admonition to us all.