The Flower Called Indigo:

An Inkblot Ekphrasis

Julie Marie Wade

for Brenda Miller

1.

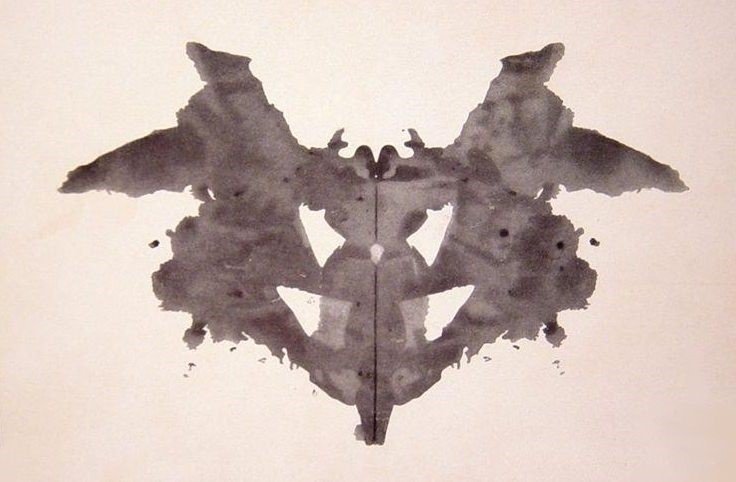

Is she Mrs. Butterworth because I'm hungry, or am I hungry because she's Mrs. Butterworth? I see a woman standing upright, ankles touching, a bell-shaped skirt cinched at the waist with brown belt and white buckle. The buckle stands out—an opal perhaps, or a moonstone? And surely that's an apron she's wearing, the darker brown partially concealing the bottom half of her dress. I'd know a woman's body anywhere, I think, this one curvy as the glass bottles of syrup we passed by at the store in favor of something bulky and generic. Now they're plastic, like everything else. If you drop Mrs. Butterworth, she will not break, but she will also not break down. Is that syrup splattered to the sides of her—sticky puddles caricatured? comment on the mess a sweetness often makes? When my eyes travel to where her head should be, there's only the collar, it seems. A headless woman with hands like pincers raised. Shades of insect? Shades of bat? Shades of the Mothman, feminized? How is she shouting without a mouth? How does she caramelize sugar into fright? Why am I no longer hungry?

2.

An incision has been made. Sterile gauze to staunch the blood. Do intentions define a wound, make it more or less wounded? Too expert to be gash, too calculated to be slash, so we call it surgical—the slit of great precision, the body made to open on command. Forceps to either side perhaps, like door jambs. A keyhole of hard, corporeal light. "First do no harm . . ." the physician swears with right hand raised, yet the promise is impossible. Isn't an elegant laceration always an oxymoron? I asked the surgeon how many organs he had removed. "A lot," his imprecise answer. "I've been doing this a long time." How was I suddenly the one who wanted numbers when words have been my lifeblood all these years? And there's the blood again, seeping into my language as under the surrounding skin. This was my first organ lifted out—though not my last. Throat splayed. Butterfly unpinned. I have trouble imagining the biohazard bag, distrust instinctively the phrase disposed of. Healing begins with a dark perforation, then a lighter version of the same. Torn notebook page. Translucent tape. Contusion visible beneath the surface like a constant flush. This spectacle of extraction before the scar settled like a necklace, as in lace around the neck. "As you age, it will fade," he said. Nearly decorative now, these 19 years since. The surprise of what isn't missed, of what we can live without.

3.

A change of mood now, like searching for a new genre in the online queue. This one has cabaret vibes. Steampunk, too. Click musical, dark comedy, arthouse. Distinctly European, I think, with English subtitles and descriptors like "a surreal romp through [the acclaimed director's] risqué dreamscape." If minotaur is man plus bull and gryphon is lion and eagle combined, what to call a creature that's part French poodle and part Parisian dame? Named or unnamed, she's what I see here. Two, actually, each in profile and collared with pearls, engaged with her doppelgänger in a corset tug-of-war. Who will be first to snap the bodice—another hybrid, this one comprised of velvet cups and ivory tusks. Between them, suspended in air, is it a red bow tie or a red brassiere? "Ah, gender," I'm shaking my head, "how we perform you! And how you pit us against ourselves!" Sometimes gender feels playful in a mix-and-match way, like when I stopped wearing dresses but went all in with pussy bows. The boyish fit of a trouser paired with a girlish flounce at the throat. That quiet thrill I couldn't quite explain. But now when I look again, forget the bra or tie; they're shackles, open and ready to clasp. Gender is this, too: a red restraint—bright as a dollop of jelly and primal as a spatter of blood. I can feel how hard the dog-women are tugging, but when they break this stricture, another awaits. Hovers above it like latter-day Spanx. So what to make of the red trapezists descending each side of the page, their bodies amorphous (ungendered?) and dangling upside down. Maybe gender is always an angel on one shoulder, a devil on the other. Advice goes in both ears, like taking two calls at once. But alas, unable to parse the messages, only a howl or whimper will ever escape the lady-canine's mouth.

4.

Everything is larger in memory and in dreams, proportions distorted by time and darkness. Surely this is why I slept with a nightlight as a child—so when the monster emerged from under the bed or behind the closet door, I would see it. I wanted to look my marauder in the eye. Head of raccoon and torso of wolf, with thick, furred feet and a beaver's tail—this hulking figure would lurch through the shadows to end me. Even then, I did not believe in escape. Big Foot in the forest, Nessie in that distant lake, and the Boogeyman, catchall name for a sinister presence that lurked in corners of home and mind. Falling asleep was easy. My father sat by my bed and wound a music box. When he traveled for work, it was my mother who sang and rocked the mattress gently like a boat. Best was waking from a dreamless sleep to natural light seeping through the shade. That deep stretch and long sigh—my end deferred for another day. The monster, you see, was never an if but a when. More often, though, I would wake mid-night to a disfigured room, the door ajar, the hallway beyond it filled with black fog. Did my doll's eyes flutter? Did the mirror rattle on the wall? Did the rocking chair creak as if a body had risen to its thick, furred feet? Yes. The answer was always yes. At six, it's permissible to be scared, perhaps expected. At ten or twelve, I was "pushing it," my father said, his perfect patience beginning to show signs of wear. "There's nothing there!" my mother snapped, though I took no comfort in the prospect of a void. Late into adolescence, I still rose in secret, edging my way down the long hall, hands extended beyond my sight. Every quarter-hour, the grandfather clock called out. Sometimes the rain would answer, tapping a message on the window glass. Meanwhile, I stood for hours at the threshold to their room, silent, unmoving, as I listened to their breath. Did I think the monster wouldn't find me there? Or was it me, all along, the hulking figure in the dark? Can it be that I have always been most afraid of myself?

5.

When I see something that resembles a bat—that telltale wingspan—my mind likewise stretches quick and wide. Adam West on old TV. "The shark repellent, Robin!" Boff! Thwack! Kapow! A parade of interjections, each in their own balloon. Superheroes with alter egos. (I wanted to be one, too. Catwoman, not Batwoman.) Why did Bruce Wayne choose a bat in the first place? The opening credits of The Munsters and Scooby-Doo, where bats swarm the night sky in black-and-white or Technicolor cartoon. What is a group of bats called anyway? A colony. Yes. A cloud. Yes, especially in flight. A cauldron. That's my favorite. Where there are bats, there seem to be witches and black cats. We have black cats but not bats—though if we did, would we even know we did, bats being such stealthy nocturnals? When they tore out her kitchen wall, my sister-in-law found two bats behind the brick, bodies long and flat, eyes squinting at the harsh fluorescence. One raised its hand—she was surprised to see four fingers and a thumb, just like ours—then hissed and swatted the air. "I didn't know you were living there," she apologized, then flung open a window. The bats left in broad daylight. Flying for a bat is like swimming through air. Something to do with the webbing that links their limbs to their wings. A new Batman movie just opened this week. A theater would be a good place for a bat to live, high up in the balcony or the rafters. My wife says the best Batman movie was the first one—they should have stopped there. I didn't see it because my father thought it would "give [me] bad dreams." Ten years ago, a man shot up a theater in Aurora, Colorado. It was a midnight screening of The Dark Night Rises. That gave me bad dreams—then, still. In Kentucky, where we lived at the time, we had talked of going to see the film, though we both agreed it wouldn't be good—too heavy on stunt violence, too weak on character. After the shooting, we never watched on principle. Days later, I heard from a college friend. His wife had gone into labor the same night. He rushed her to the hospital, where victims of the shooting kept pouring in. I think of the screaming, the blood, life and death juxtaposed so viscerally, and then I think of bats. Batman feels more like the villain now. I conflate him with the man who threw tear gas into that crowd before he opened fire. Sometimes my grandmother said "Bats!" instead of "Rats!" It was the fiercest profanity she knew. When someone says "blind as a bat," I always cringe a little, wondering if they know about my lost left eye. (If it was so "lazy," though, how did it wander away?) Recently, I heard the expression "bats in the belfry" for the very first time. Loved the alliteration. Loved the image it sparked. Didn't love the way the woman who said it looked right at me, sharply, then away. Bats!

6.

Who was it who wrote Euphemism is candor in a cloak? It's a cloak I see here, which might also be a bearskin rug or a coffee spill on white linoleum. These are my second takes, though, impressions I've coaxed forth to replace the first. Why was I so reluctant to say I saw a woman's body, uncloaked, spread wide?—and these still euphemisms, mind you. What does it mean when we have the words but choose not to use them? And does such withholding have to mean shame? I recognize the same feeling when slicing papayas, the green body suddenly splayed into two pink halves, smooth and abundant with seeds. It's awe followed at once by reproach, as if a tiny voice in my ear were chiding: You shouldn't see what you're seeing. After the body but before the cloak, I thought of a poem I love by Li-Young Lee that begins, "It's late. I've come/ to find the flower which blossoms/ like a saint dying upside down." Here is that flower. Here is that saint. I see them fused on the page, beatified before me. It's been more than 20 years since I first read Lee's poem, as a young woman late-arriving to her own inflorescence. "I've come to find the moody one, the shy one,/downcast, grave, and isolated." I was not her, but I was searching for her. Is flower always a euphemism for the woman we desire? And is woman the word-cloak we always drape over her body, over the parts of her which are hardest to name? The speaker searches for a flower called indigo. He calls her "my secret, vaginal and sweet." I remember how the word "vaginal" caught in my throat, synonymous with a gasp. Were we allowed to say that word in class? Were we allowed to say that word aloud? Meanwhile, in the poem, the indigo flower unfurls herself "shamelessly/ toward the ground." She's blooming upside down as promised. I can't tell now if this poem is paean for desire or elegy for death that always comes too soon. Once, I thought I knew. I can't tell what the poet intends by this closing epiphany: "You live/ a while in two worlds/ at once." Could it be euphemism itself? One world is what we say, and the other is what we reveal. Two worlds layered, seen and unseen, half-blossom, half-root. And the one who wrote Euphemism is candor in a cloak? That flower—woman—body—was me.

7.

I see teeth first, like an X-ray the dentist clips to her illuminated board, saying something sweet and obvious like This is the inside of your mouth! On second glance, they're sugar cubes, which I've rarely seen in real life but which I know are terrible for your teeth—too sweet! Sugar cubes might lead to the very X-ray this image evokes. When I look a third time, though, it's ice floes I see, drifting and breaking apart. There's a squeaking sound I heard once, kayaking on a broad Alaskan bay—a sound that stays with me. Now the phrase climate change floats through my mind for the dozenth time today. Unlike the ice, it doesn't decrease in size. How neutral climate change sounds while describing everything that isn't—shrinking glaciers, rising temperatures—in other words, matters both urgent and dire. The dentist thinks I've been grinding my teeth and hastens to reassure me this is "very common." She adds that many people who never ground their teeth before "started during all the recent political turmoil and following the rise of COVID-19." She's good at keeping a neutral tone, talking with her hands, choosing words that won't make my teeth chatter like they do when I watch the evening news. "Are you cold?" my wife asks as she hands me a sweater. "Worried," I say. Worry has always made me cold, even in Florida. (Especially in Florida.) The dentist says I'm a good candidate for a custom mouth guard. The crack along the base of my teeth is thin now but will likely widen over time. And do I ever get headaches or wake up with a sore jaw? Yes, I get headaches, perhaps more in recent years. But no, I've never felt any soreness in my mouth at all. What I'm too embarrassed to tell the dentist is what I realize on the drive home: the crack isn't from grinding my teeth—it's from chewing the half-popped kernels at the bottom of my popcorn bowl. I know I shouldn't, but they're oddly irresistible, part dove and part stone. I crunch them hard. I relish each bite. And now, when I consider this image a fourth time, that's all I can see—popcorn. Perhaps a string of it, like the festive garlands we made for our Christmas tree long before anyone thought to ask—Shouldn't we be planting more trees outside than bringing them inside just to watch them die?

8.

Another bodice without a body, this one framed by effulgent pastels like the stucco houses of my cul-de-sac. Today the neighbor's roof is coming off, a loud, intentional process of stripping away old tiles and replacing them with new. This, too, reminds me of a body, the old cells sloughing off, dead skin giving way, then giving way again—our dermal palimpsest of perpetual shed and grow. It happens so quietly, though, not the way these tiles crash to the waiting bins below. Now windows are slamming shut and cats are rushing inside, their tender ears flat against their heads. Ruckus! the tiles bellow. Commotion! the tiles boom. Dramas of maintenance and renovation too dangerous to ignore. In Florida, roofs must be replaced every 15-20 years. Damage from sun and storms is extensive here, leaving properties vulnerable without the necessary care. In the human body, cellular regeneration takes 7-10 years, which is to say we will become approximately two new selves before the roofs on our domiciles come due for repair. The body, of course, is the primary domicile. Damage from sun and storms can be extensive for us, too. The showy colors of this bodice mask such vulnerabilities. I see a white collar popped, a soft blue bralette, a ribbed midsection in pink flush giving way to perky tangerine. Everything so beachy and balmy it's easy to overlook the hard nature of foundations—to ask what holds this all up, prevents its future collapse. Who wouldn't choose to focus on pretty garments instead?

9.

I've just learned that a friend's father is suffering from advanced dementia—which means that she and her mother and sister are suffering from his dementia, too. April is my oldest friend, though it seems misleading to put it that way, given how many friends are years, even decades, older. The phrase should be longest friend, I suppose, as in I've known her longer than almost anyone. Once, we were young enough to cover her driveway with a mural of animals we loved: seahorses, llamas, turtles, and gulls. The chalk we used was jumbo-sized and came in bodacious colors called fuchsia, banana cream, and sea foam green. I remember her father coming home from work in his zippy gold car and how April pleaded with him to park on the street, then hurry down to admire our handiwork. Mr. Davis had long, silver hair he pulled back in a ponytail. Mr. Davis pumped iron at a gym at 4 AM before heading downtown to drive bulldozers for the city dump. Mr. Davis wore stonewashed jeans and a denim jacket with thick fur trim. When he took it off, his enormous bicep flexed, and I watched the black anchor move up and down his arm. "I can dig it," he said, grinning at us, his voice always softer than his sturdy body would suggest. April says he's agitated now and refuses to rest, stumbling around the house, breaking things, always talking to himself. "He doesn't recognize us anymore, and we can't leave him alone, even for a minute." Once, I was young enough to believe Mr. Davis might be a comic book hero. When I learned his first name was Jim, I had to ask, "Did you create Garfield?" He laughed and shook his head, but then he squatted down in his stonewashed jeans and lifted the orange chalk out of its box. "For how much you girls love cats, I can't believe I'm the first to draw one." It's hard to believe more than 30 years have passed. It's hard to accept that I wouldn't recognize Mr. Davis anymore. A few years ago, he friended me on Facebook, sent a sweet note reminiscing about all the mischief April and I used to make on the block. Once, we were young enough to still believe in Mary Poppins—believe we might jump into our mural and land in a different world. Before we could try it, though, there came a hard spring rain, and all the animals we loved—the orange cat, too—swirled and smeared and suddenly washed away.

10.

There's so much I don't remember about the science I learned in school, so much I never understood. But the words remain, obdurate and inviting. Here I see a karyotype in color, all the paired chromosomes wriggling, lively, a jig of possibility. And as I write the word karyotype, I'm reminded of another word, an echo—caryatid—this one first encountered in art history class. A stone carving of a female figure used for architectural support, caryatids lend themselves quite naturally to metaphor. Women as pillars. Women as columns. Women who carry us all. I look again. The word all casts a long shadow, stretches into the word allele. Why do I feel I've glimpsed some here? Long squiggles, complementary curves. I refresh: "Different versions of the same gene are called alleles." One Science Basics website cheers, "Alleles create diversity!" And so we are: plentiful, diverse, induplicable. After our cat died, a friend hand-painted a card, swirled and splotched as this one—piebald. There's a memorable word. Inside she wrote, "There are so many cats to love. There are so many cats you will go on to love. But there will only ever be one Tybee." Yes, just one. Now I see paw prints. "They're like fingerprints," a vet once told me, "every one unique." And now it's Annie Dillard I'm thinking of, the twin ns and ls of her name and that illusory symmetry we seem to crave: "some mornings I'd wake in daylight to find my body covered in paw prints in blood; I looked as though I'd been painted with roses." Now I see roses, too: bouquets and boutonnieres and burial arrangements. Woman as writer. Woman as naturalist. Woman who also loves words. It no longer matters to me that Annie Dillard never had a cat.