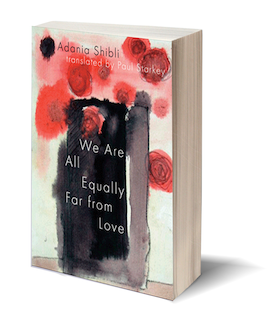

We Are All Equally Far From LoveBy Adania Shiblitranslated by Paul Starkey

Clockroot Books |

|

|---|

Yesterday, while it was still fine and hadn’t yet started to rain, I went with the neighbors’ children to a local park to play. The four of us ran around, hiding here and there, and there were lots of butterflies that looked as if they were playing with us. Afterwards we sat on a large rock, and it was then that I discovered I was seeing everything in order to write about it to him. More than that, I discovered that I had forgotten how to live without his letters. It made me afraid of finding myself one day without them.

A few hours later, when I arrived home, I found a short letter from him.

We had been exchanging letters for two years.

I’d written him my first letter at the suggestion of my boss, to ask his opinion on something, as he didn’t like talking directly to strangers. I composed my words carefully, and a little fearfully.

Two days later he replied cursorily, and perhaps with a touch of warmth. I could detect this warmth between the words, and it made me happy for the whole of the afternoon, for no particular reason except most likely that I was a weak person who was touched by hints like this, and quite easily.

The next letter I sent to him went out a month later, asking him again for his opinion on the same matter, for I hadn’t completely understood what he’d told me the first time. He replied. His second letter was also short. Both his letters to me were shorter than mine to him, and he also concluded them more abruptly than I did. He wished me “Best,” while I closed my letters with “Best wishes.” I don’t know why I offered more right from the beginning.

Then the days once more started to pass as they had before, uselessly. I wasn’t happy with my work, nor with anything else. I was living mechanically, doing everything with a sort of lifeless proficiency, though the presence of his two letters in a file on the shelf in my office forced me, illogically and inexplicably, to go to work each day. His two letters, plus a walnut tree whose branches hung over a house wall and across the sidewalk where I walked to get to work. Every day I would pass under those branches. I could have crossed to the opposite sidewalk, but I had become addicted to the sense of pride that flooded through me when I had to lower my head to pass under the tree, especially in winter when its slender, leafless branches became more fragile. At the end of spring, the branches would start to fill with leaves, forcing me to stoop lower, while in fall, those same leaves would race me as I walked on, until they would suddenly stop, or blow away in a different direction.

His two letters had a similar effect. Like the tree, they were able to touch me and my loneliness, and the kindness that emanated from them did not disappear with time. I even found myself wishing that I could think of a new subject to give me an excuse to write him a third letter.

But everything in my life was monotonous.

I wrote him a third letter.

I told him that I had quit my job and moved to live somewhere else. Here was my new address. I wrote a number of similar letters, which I sent to some acquaintances, to lessen the sense of stupidity and the alienation that I felt from myself. I hesitated for a long, long time before sending him the letter.

He didn’t reply.

Some weeks later, a friend pointed out to me that there was a mistake in the address I had sent him. I felt utterly stupid again, but this time it was stupidity of a different kind. I corrected the address then re-sent it to everybody, but not to him. Better not to.

Perhaps what had drawn me to him from the beginning was the beginning itself, when my boss asked me to write someone a letter instead of speaking to him on the telephone, as if the person in question found great satisfaction in isolating himself. No, he didn’t want to talk to anyone, and there was not a single hope in the world that would lure him. The shortness of his two letters to me suggested that he didn’t even regret this isolation. I, on the other hand, had never been able to say “no” in my life; I was always full of illogical hopes. Perhaps my desire for him was one of these hopes.

A few days later I sent him the correct address.

Had he not replied?

Then I dissolved in a sort of feeling of contempt for myself, and tried to forget him as much as I could.

The new house that I’d recently moved to had hastened the stages of my withdrawal from living and other people’s troubles. The new job was just like nothing, or worse, for even lunch during the midday break had lost its flavor. Then, as time went on, the kitchen tap started to drip, until eventually it no longer bothered me.

After that, the rain started, and I would remember the walnut tree, and how the drops of rain would stay there suspended on its branches even after the weather had brightened. I would walk under the tree and sometimes bang against a branch, which would shake so that raindrops fell from it. How nice that was.

It was still raining outside when I heard the garden gate move, and my elderly neighbor came in. She started to deal with the drain, removing the dry leaves that had collected on top of it. “Why don’t you write to him again?” I said to myself. “You reached a high point of stupidity the last time, so a fourth letter can’t do much harm.”

But he replied. He talked about the cold, and how bitter it was. That he didn’t like the town I lived in, and wasn’t particularly interested in trees. Finally, to solve the problem of the tap, an ancient Greek philosopher had advised wrapping a cotton thread around the spout, so that the drops of water would flow gently down the thread and disappear into the drain.

From that day on, the letters between us never stopped. At first, they appeared an average of once a month, then gradually this became once a week.

My letters to him at first began “Dear Sir,” and continued with “Dear Sir,” until suddenly these two words acquired resonances and connotations that I felt I needed to be wary of, so I persuaded myself that they were not there.

Despite this, it was only when I was writing to him and reading his letters that I would feel myself. For although I had never in my life heard his voice, never seen him, never touched him, he aroused in me something that stirred the desire for life.

I started trying to find other meanings and hidden worlds in the words he had written. If he ended a letter with “Love,” I would find myself searching for all the connotations and allusions that this word might have, using the dictionary as a neutral and reliable source of information.

Then I would think things over and try to persuade myself to calm down. But to no avail. He pursued me like a breeze behind my neck. I could feel him quite close to me, even on the narrow path leading to my house. I could feel him every morning, when I heard the sound of my elderly neighbor, at first behind the bedroom window, then later behind the kitchen window as she shut the door behind her and walked over the stones of the garden path, followed by the slow crinkling of a plastic bag.

How much he wasn’t here!

But we were writing. He was perhaps the only person that I felt was able to see and completely understand the sort of life that I found myself living, where the three most important things to me were a walnut tree, watching the movements of my elderly neighbor, and waiting for his letters.

He would send me a letter that reached me every Sunday morning, while for my part I would write to him every day. Still I would wait until Wednesday before sending him everything I’d written, for I was afraid that he would become bored and desert me if I sent him a letter every day. This fear made me sad, but I gave in to it nonetheless.

But I didn’t admit that I was in love with him until that short letter reached me yesterday, asking me to put an end to our correspondence and not to send him any more letters.

The tears leaped to my eyes. I would have liked to tell him no. I should have, but instead I sat and wrote “I love you,” and then everything.

That was the first letter. He didn’t reply. The pain was intense, but I paid no attention, and wrote the second letter. Again, he didn’t reply. The pain became more intense, so I wrote a third letter, and felt at peace. I wrote without needing to wait for Wednesday, three days were enough. I wrote a fourth letter, then a fifth, willing myself not to write any more.

I think about him all day long. What’s my mistake? That I love him? That I’ve started to love him? That I’ve told him I love him? That I don’t know him at all?

I am tired. Even the noise of the plastic bag between my neighbor’s fingers has begun to hurt me.

But I wrote to him again. I no longer cared about anything. Everything was heading towards death, with nothing to stop it.