Nick Francis Potter

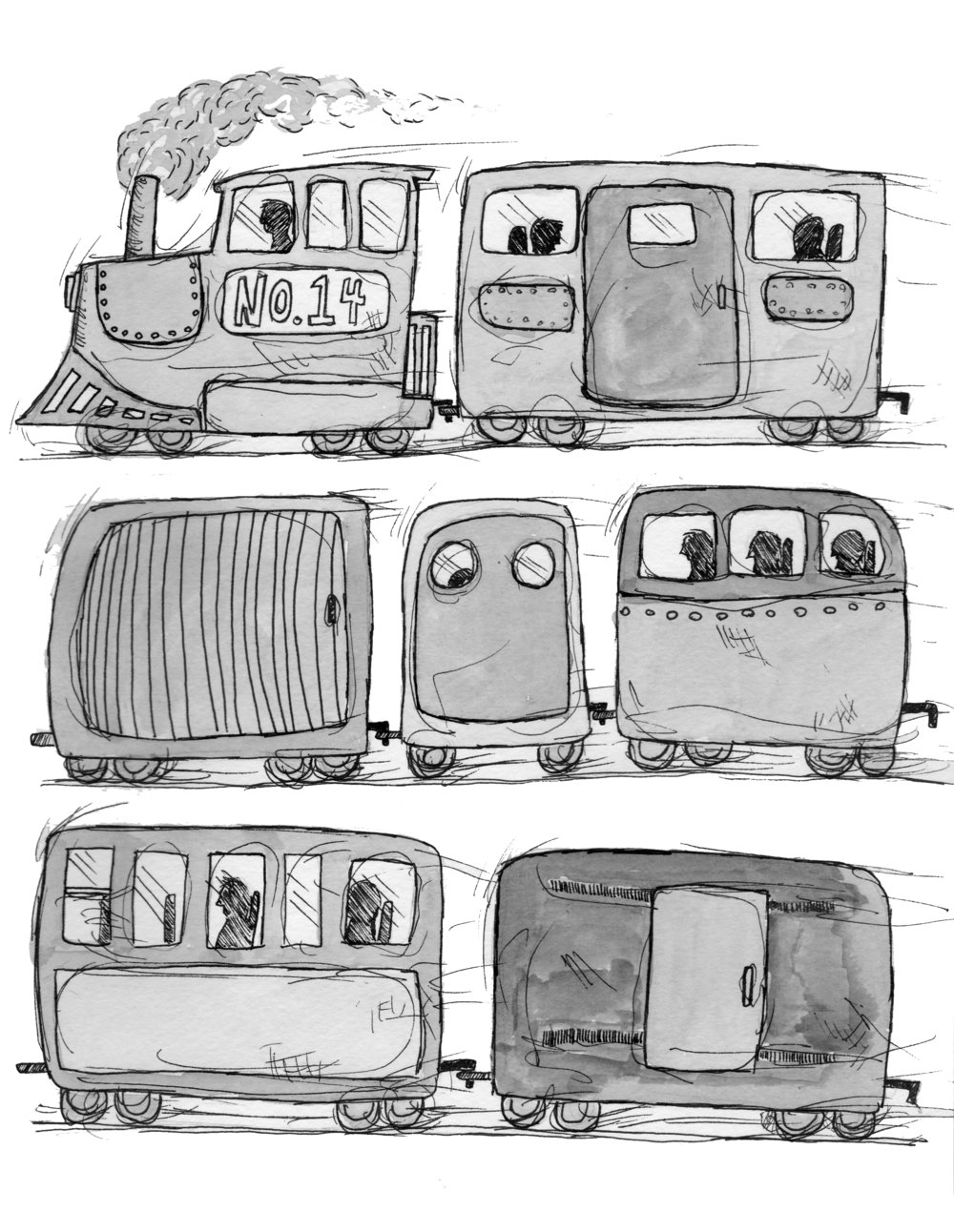

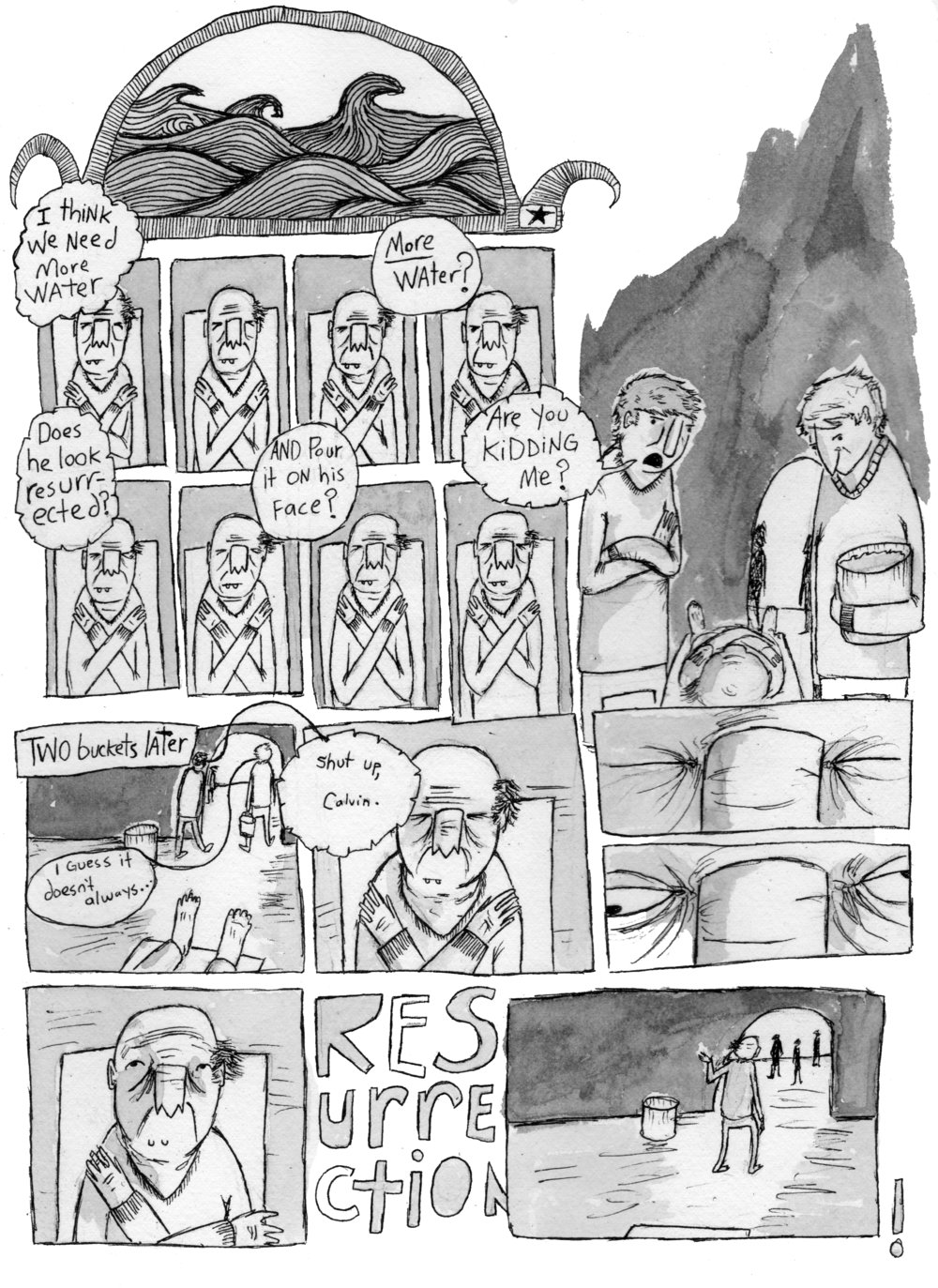

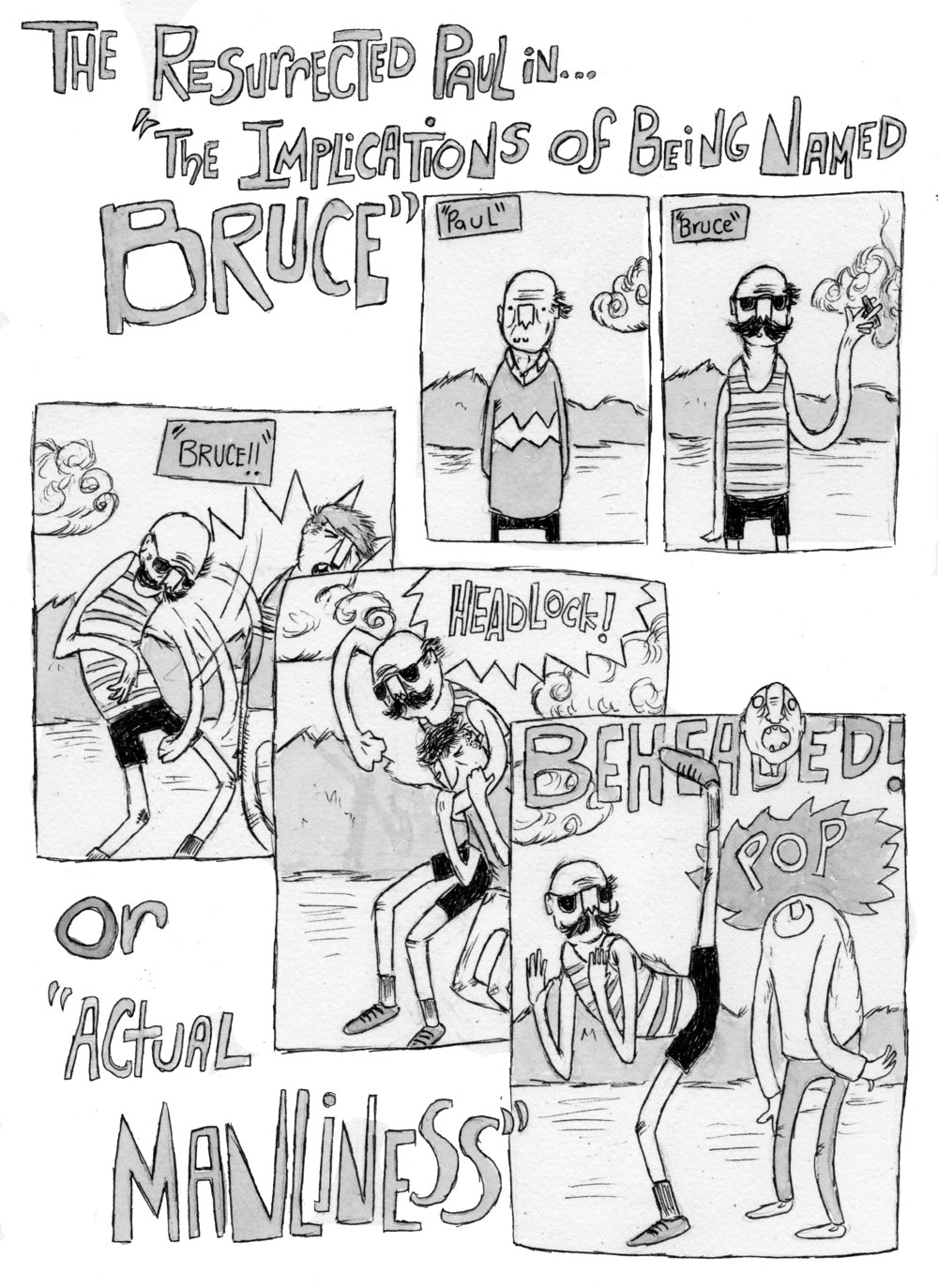

This happens: Cleveland and the troops unwittingly find a tomb. Paul's tomb. Paul isn't an uncommon name; maybe Cleveland, maybe one of Cleveland's troops, knew Paul. Or read about Paul. Regardless: a resurrection takes place. One of the wetter resurrections of the past few decades, facts be facts, as Cleveland and the boys using plenty of liquids when they resurrect. Buckets of water suspended above some spiraling wooden gears, a pulley or two—two pulleys—and Paul's caving frame fenced in by the wetbrown equipment—lucky they had their equipment!—everything soaked and pulsing, rigidly. There's a steady, high-pitched creaking (resurrection is a noisy enterprise) and then a happening: Paul up and standing forth, wiping the sweat of resurrection from his brow. Cleveland and the gang exchange toiled grins, exhausted, but satisfied at their success. Some spit exits their mouths, marries the dirt. He, Paul, wobbles forward, bracing himself on the frame of the tomb door. Centuries have thinned him to a tight sack of leathery bones. His hair, his fingernails, now long, patchy threads of deadened protein. A ruffled portion over his ear. The right one, from Cleveland's position. It's not the sight one expects to see. Cleveland, too, thinks so: resurrection isn't what he thought it would be. (Where was the silken aura? The spectral illumination? The confetti?) Have they performed it properly? Perhaps not. It's a smaller triumph than originally expected. And now what?

The resurrected Paul, noticing the quizzical looks of Cleveland and his cronies, the questioningness sharp on their faces, makes a suggestion: I think if I had a towel to dry off, I might look a pinch more comely, do you agree?

Kendall is positioned near the back of the group. Kendall doesn't mind saying so: I'm bored. I say we just get rid of it. Let's get rid of the head, and all of it really.

Paul contends through a dry, wispy, cloth-spewing exhale: Perhaps, he pauses, finger up in the air, pausing. Perhaps, I could stay awhile. I really just arrived, didn't I? I could massage your feet, each one of you—and stir up some tea while you each manage some sitting time? I imagine there are plenty of activities we could think up with some of this daylight.

They, the group of them, exchange looks, bemused, having locked jaws. Cleveland says, Well Paul, you see, we're not much for foot massages, particularly when performed by meatless palms. And you have meatless palms. Also, tea is not our sport. Not in the least. We're men.

Ah, well, Paul continues, perhaps we could attend to a lake somewhere—are there any lakes near here?—up a good tire swing. I could read to you all as you wade about in the water. I don't know what books you have on you, but I'm a handsome sight-reader.

Now Paul, Cleveland responds, what's this of reading? What do you make of us? Students? We are the type to resurrect—re-sur-rect—not to wet our hair in a lake or float belly-up like some lazies. You're pitching us tire swings? Our status is this: MEN [Cleveland holding up a black painted sign with "MEN" written in capital letters].

Then, quickly—no thinking here—it happens with shovels. Lots of smashing and cleanly shattered marrow. Little blood. The whole lot of them converging upon him as one. And so it is that the new Paul is collapsed upon by a heap of shovels, all thunderous and clanging, the light particles of old skin lifting from the ruckus, then floating softly back down to the earth.

Instead: The "MEN" think on it and, following Cleveland's lead, pull out retractable chairs, opening them to their furthest, on their stretchedest hinge, their shovels unsullied and free from guilt. It's a few minutes of rustling, but eventually, after settling their chairs, they sit deep, pondering. The possibilities! We did go to the effort of resurrecting him, they think. In the ponderous silence an opportunity for kissing sneaks up. An opportunity for kissing? Such moments are hard to define, but, inexplicably, they occur, and—as it is at this moment—often when one least expects. Paul acts oblivious, leaning back casually against the outer wall of the tomb, dryly whistling (he's never learned whistling). The cloud of opportunity weighs uncomfortably on the "MEN," hovering low, pecking at them. Its eventual departure is a relief to all.

Paul takes advantage of the opportunity-cavity left by the opportunity-for-kissing. I don't mean, spoken sheepishly, to burden your ponderings, but (and we imagine that Paul's revived heart is thumping with anticipatory madness here), but, what are the chances that lemonade or a lemon-fizz drink is available? I'm parched. I really prefer the pink kind, but yellow's okay by me.

Immediately, Paul has a glass in his hand, a chair to sit in, an umbrella for shade. It appears that Cleveland's men can be very accommodating. Perhaps they're not so ravenous.

Someone speaks up. It's Dallin. Lanky Dallin.

You know, when we were making our way up here there was those train tracks we passed. We could try him out on those.

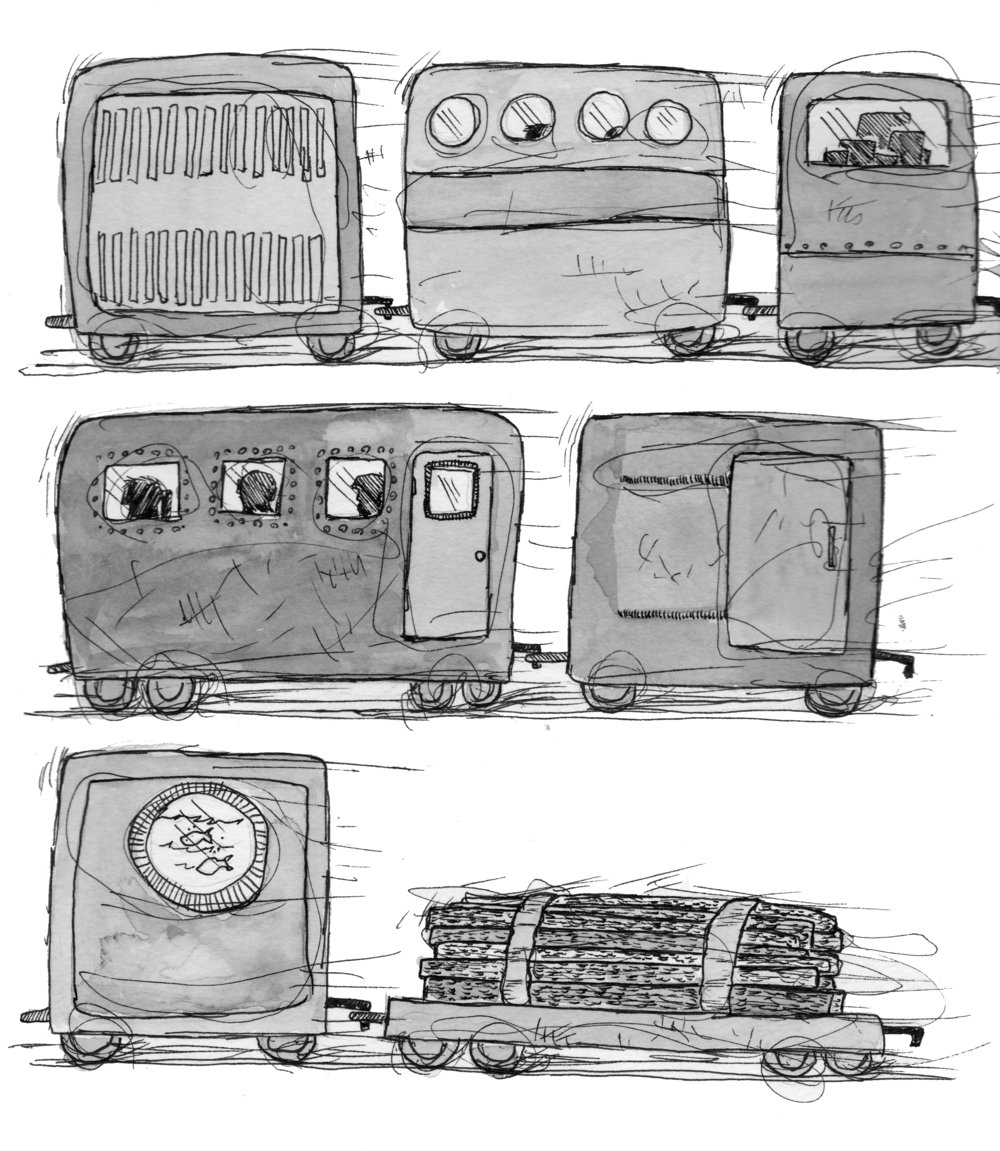

It's a couple hours before the train, just a teenage train, a lemon-fizz train happily enough, fizz drinks steadily tumbling from the back of the caboose, is turning the corner, Paul's left arm stretched across the track, not willingly of course, but strictly tied now and unmoving, Cleveland and his crew, a halfmoon audience all straddling their 10-speeds, the bicycles dirt-full from the trip (Paul riding handlebars with Cleveland), a few of them wearing earphones, dubstep pulsing, R&B, the train trolleying closer and closer, cringing in advance of Paul, that metal chugga chugga burning against the tracks, but it's too loud, and, after some minutes or so, minutes spent mulching through flesh and marrow, the train is gone, and Paul laying there, still, his arm segmented at the wrist and at the shoulder, releasing him from the track.

Paul's blood, archaic as it was, coagulated into thin strings that hooped limply, hanging long from his opened arm.

Now what?

Now This: One arm gone, Paul gets grumpy. Ill-tempered arm folding requires two arms. Still, Paul manages to adequately convey his grumpiness. Don't be like that Paul. How about if you make the next pick? Cleveland's offer doesn't change any of the details on Paul's grumpy face. Cleveland and his company are embarrassed. Eventually, Paul does accept Cleveland's offer:

I'd like to change my name.

They gasp. Marv, a taller member of Cleveland's crew, falls from his bike. Fortunately for Marv, parked near the back, few notice.

Call me Bruce.

Hesitation abounds. This is a big change for Cleveland and the guys. They resurrected a Paul, not a Bruce. But, in the end, Cleveland submits:

Alright, Bruce.

Paul, now Bruce, immediately grows a full handlebarred mustache, thick and black, knife-sharp at the tips. The implications of being named Bruce are marvelous. The men provide Bruce with sunglasses, neon, triangles running along the arms. They are very accommodating.

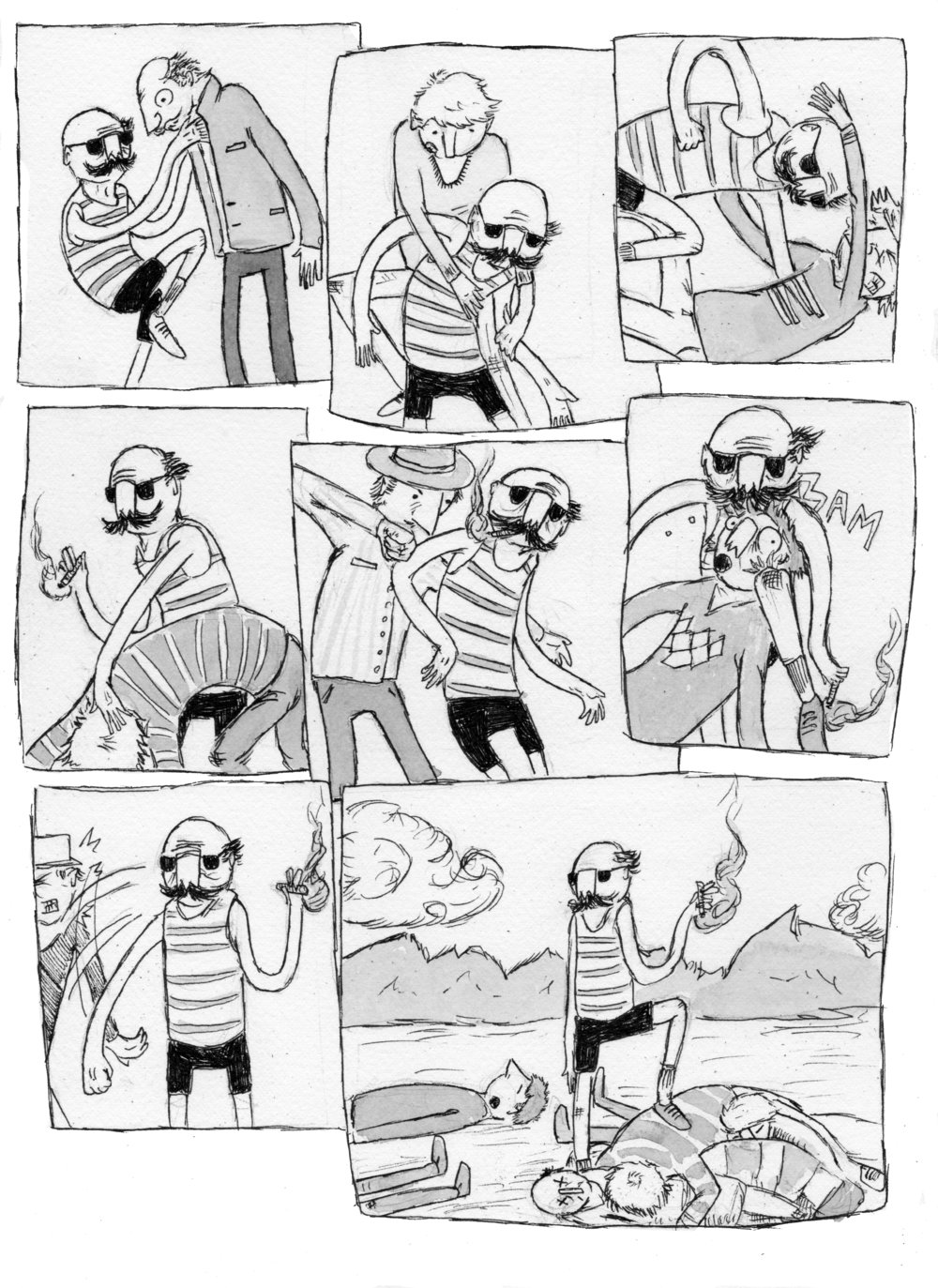

To the beach! Bruce proclaims, his lone arm outstretched. Excited, the men begin to foot at their pedals. Cleveland, however, is not so excited as his crew. Why is this Bruce character suddenly so cool? he thinks. I'm cool. Perhaps Cleveland is a tad insecure because he himself has never been able to develop a full face of hair. Instead, for Cleveland, it grows in all patchy, his rough cheeks barren but for a few tangled strands of beard. He likewise has found he is unable to cultivate any visible growth of mustache on his upper lip, his red-blonde hair appearing mostly transparent, even when conditioned for shine in the daylight. The inability to grow facial hair weighs heavily on his status as a leader of "MEN." But he says nothing.

Riding now the stretch toward the shore, Bruce perched on Cleveland's handlebars, not unlike a prince, Cleveland green with envy, his nose cartoonishly, angrily red, the handlebars of Bruce's mustache fluttering against the breeze, the handlebars of Cleveland's bike trembling lightly, pleasantly, expectedly, Bruce doe-eyed at the prospect of a beachside suntan, Cleveland with an idea: the brakes.

The brakes!

Bruce unprepared. Bruce soaring. Bruce tumbling and crashing. The men stopped amidst the commotion, astonished. Bruce, a contorted heap. Cleveland off his bike, approaching calmly, seemingly, grips Bruce by the skin, still wet and loose from the exertion of resurrection, and shakes out his bones. It's enough to end him again.

Instead, back to this:

Instead of that, this:

This happens: Paul resurrects, a tormenting figure, ragged and uncertain-of-step, his sick, yellow eyes lounging low in their sockets. Cleveland and the troops are not impressed, disgusted actually.

Seriously, Cleveland, why'd we do this?

Shut it, Kendall. Let me think.

And they pause while he thinks.

Got any ideas boss? says Dallin. Lanky Dallin.

Nope, can't think of any. Let's get real: we're not "MEN." We might as well ask our mothers.

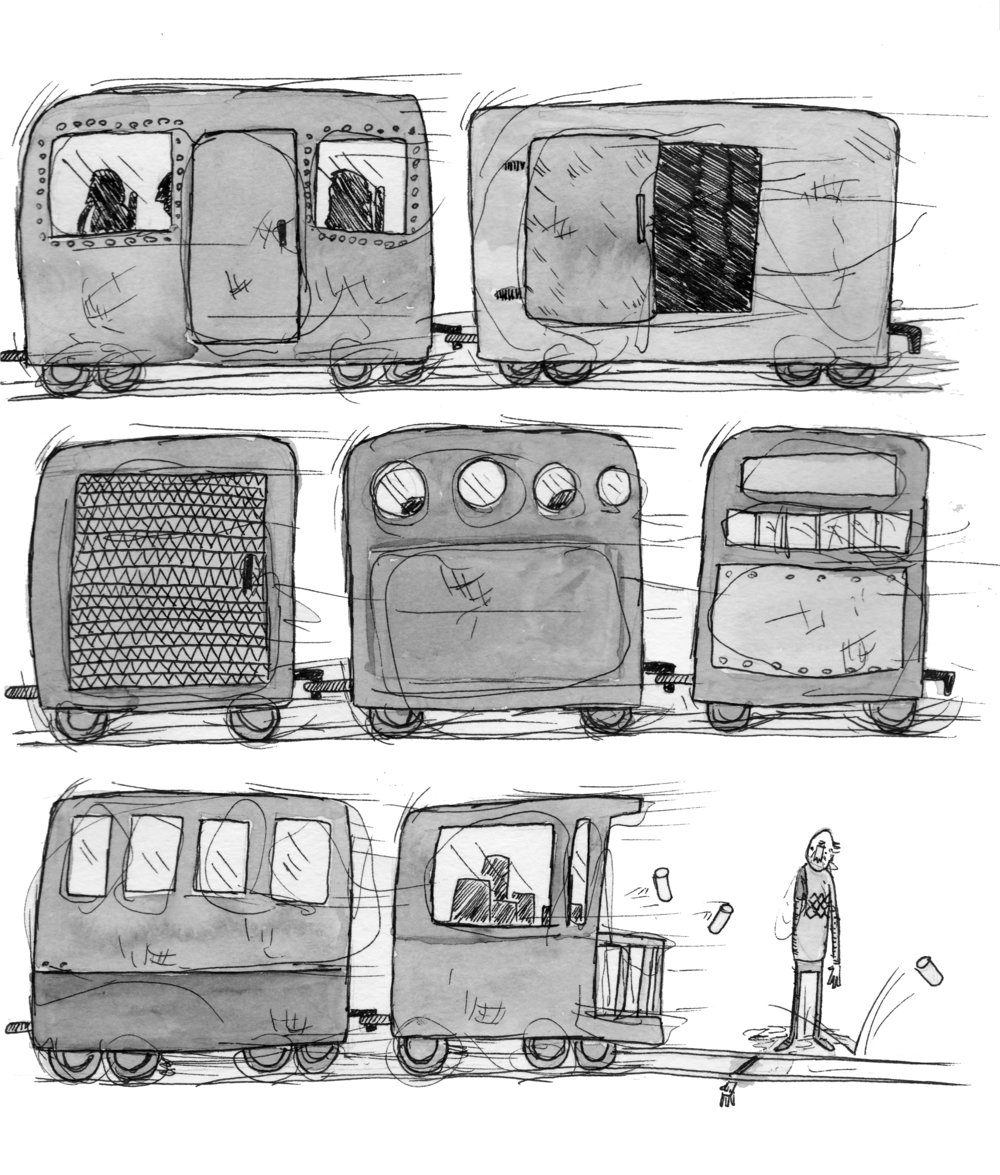

By this time Paul has gone wandering, in a slow, lumbering shuffle a hundred or so feet away, silent, simply wandering, like a lost Alzheimer patient. Cleveland has a couple of the men herd him back toward the group, then telephones a busing service in order to travel their mothers into camp.

It was some hours before they arrived, hours in which the yo-yo made a brief appearance, infiltrating the minds and knotting the fingers of various members of the troop, lovingly enchanting them until Cleveland, the taskmaster, restored the manly demeanor (a demeanor one expects of individuals or groups performing resurrection) with a reminder—a silent reminder—enacted simply by his flashing a black painted sign with "MEN" written in capital letters, and the yo-yos were pocketed. It was a span of hours in which the resurrected Paul was lost wandering no less than three times, and was eventually tied by the ankle to a shovel which was operating now as an anchor, having been submerged deeply into the soil; hours in which the closing of eyes was common and not considered an admission of weakness, as it previously had been, there being so many hours that passed before they, their mothers, arrived.

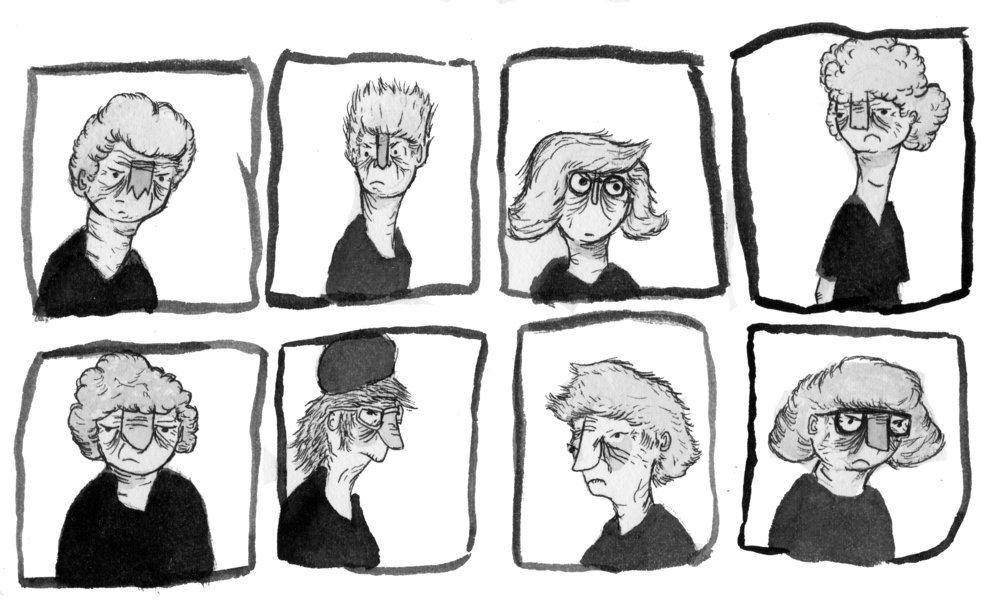

The bus arrives. It is heavyset with the musk of womenry. Their mothers exit the bus, nostril's humming, engulfed in an astral float of dust—their own particle history—orbiting them constantly. It's been some years since they'd bused their mothers in on a job. Cleveland picking at his throat like a harp, noting their birdlike hunches, the course of wrinkles rivering their skin, their matted spheres of translucent hair, their spectacles, their dresses shingled thickly in black oil paints, their heads hanging forward as if supported by nooses. They've finally exited in full, the tallest one's mouth warbling, motheringly doling out wavered condemnations with a measured smile.

The group is, for the most part, too far out of range to hear.

The group is, for the most part, too far out of range to hear.

Paul takes some initiative, does some politicking, the dumb bag of bones, and introduces himself to the whole line of them, shaking the hand of each, his cold fleshy grip slippery like a descaled fish, freshly blooded, matching the ancient women bone for bone in each transaction. After allowing their pleasantries, their little introduction, Cleveland lays it out on the table: We've resurrected him, now what?

They huddle, briefly, though, the time it takes for them to gather together into a huddling and then return to their original formation, a strict line, a wall of motherhood, is not quick. The taller one, previously noted for mouthing wavered condemnations, is provided with a bullhorn by Marv (she being his mother specifically): He was gentle with us, handling our wrists and fingers. He seems harmless, son-like. He seems to be unhealthy as any of you have been at any point and to have the possibility for being as purposeless as each of you have turned out to be, to have a knack, possibly, as each of you have had, at one point or another, for the piano, though we expect, as was the case with you, each one of you, that he would, after a lengthy period, right when he would begin to catch his stride—the stride-catching period being after a year, maybe two years—would bare down on us, whining about how he didn't want to play the piano anymore. And we, being mothers, would refuse him for as long as we could, but we are mothers after all, not devils, not sons, and so, of course, as we did with each one of you, each and every one, we would submit, eventually, allow him to quit, to quit playing the piano, even after we told him how much he would regret it, and even after we said he would regret it, he would quit, just like each one of you quit, just as you were catching your strides, and now, how do you feel now? Ashamed? Filled with regret? (They did, the felt ashamed and filled with regret, all of them wanted to be able to play the piano, to tear through some ragtime number at a moments notice, for a ragtime girl, for their mothers.) And, this being the case, us considering him as a son, not unlike one of you, we, therefore, we consider him dead. We suggest a shallow pond.

To this, Cleveland takes Paul and immediately drops his head down off his shoulders (Paul's head off Paul's shoulders), plip plop, just like that. Then, of course, for the sake of Marv's mother's suggestion, plants Paul's everything-from-the-shoulders-down portion in a nearby pond of sufficient shallowness.

Wait is he…?

Nope. No sir. He is not.

Actually, though: Paul never resurrects. Not ever. The men all sullen—heads down, shoulders up, like impoverished vultures. A few begin weeping and, subsequently, end up being taken in the arms of others, less shaken, for a rarely had physical-type comfort. Cleveland, overtired from his resurrecterly exertions, packs Paul up, suitcasing him, keeping him for himself, unwilling to leave him, the corpse that he is, dead and lonely in the tomb, to remain, his pockets candied (Cleveland and the gang exhausting a wide range of resurrecting techniques), inviting local animals to lick at the seams, for, despite their failure, an inability to achieve godhood, Cleveland could create something yet, and what else is godhood but that?