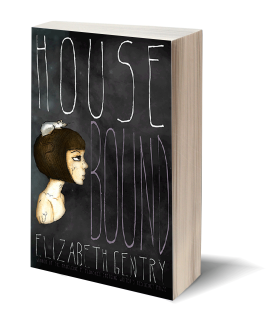

Housebound

By Elizabeth Gentry&Now Books |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Angela Woodward

Elizabeth Gentry's Housebound tells the story of a girl's awakening from a years-long slumber. Nineteen-year-old Maggie has been homeschooled her entire life, seeing almost no one beyond the circle of her parents and eight younger siblings. The novel begins as Maggie announces that she will leave home in three days to take a job in the city looking after infants at a church. As soon as these words patter down on the family assembled on their benches at breakfast, Maggie becomes an exile. She has broken a rule by mentioning her plans so directly, and she is immediately expelled from her bedroom and made to sleep on a bench in the hall. Her siblings treat her like a ghost, as if she has already left them, and she wanders like a spirit through many places that had previously been forbidden to her. She meets again the neighbors she hadn't visited in years, and the two sets of grandparents her family had long ago stopped acknowledging. She glances up at a window the children had all learned not to see, and so begins to remember a story she had agreed to forget.

The world of Housebound exists gracefully in its own space and time, as if it were entirely fantasy. The town, city, and region are never named, and glow with an eerie fairy tale light. Yet the landscape is quite palpable, indeed heavy with rural poverty, as when Maggie struggles to wash a denim dress in a bucket on the lawn. The siblings maintain a network of secrets from each other that seems heightened and surreal, but that at the same time reflects the practical strategies of children trapped in too small a house with no physical privacy. While Maggie is the center of the story, Gentry's narrative point of view pounces lightly from head to head, so that Maggie watching becomes Maggie watched, or Maggie recalled or thought about. What seems vague to Maggie—How does the clinic receptionist know her? Is this really her grandmother?—is often clear from the vantage of one of the other characters. But the vying perspectives also confound what had seemed clear earlier. Maggie's father shows himself as uncaring when he waits in the car rather than taking Maggie into the clinic to have her rat-bitten finger attended to. Yet later, we learn how lovingly he longs for her to take up her job and leave so she can be free of the poison that seems to have kept the whole family drugged for years. Gentry also creates dreamlike images—a fat lady who bites children, dark woods filled with unseen, dangerous tramps, a mermaid trundled through the woods in a wheelbarrow—that in later iterations take on a plain, country scariness, not fantasy but vicious reality. Gentry uses these many devices to keep the story unbalanced and unsettled, a gently undulating, slightly seasick motion created in sentence after lovely sentence. Describing the aftermath of Maggie's rat bite, when she now has nowhere to sleep, Gentry writes:

Watching her, the children knew there existed a dread greater than the return of the rat: sleeping with their mother, whom they had always imagined did not in fact sleep at all, but lay awake in a kind of trance, evaluating the sounds in the house and drawing conclusions that would inform interactions the following day. The siblings should have shared the burden of detecting the night noises all of these years. Instead they could only hear the hum of their mother's consciousness, somehow both sluggish and alert, which told them to carefully move about as little as possible.

These poised sentences elaborate a group consciousness—the combined feelings of the children who are not Maggie—about Maggie's fate, and their mother's bewitched state of watchfulness. Gentry's careful, slightly elongated constructions echo the family's almost paralyzed stasis, as they are held under this magic spell that makes them control their breath, their vision, and their speech.

Toward the end of the novel comes a ghost story that had been told earlier, about a girl buried alive. A mother has dreamed that her child is alive in the casket, but it takes days to convince the men to dig her up: "[T]he family opened the casket to find the girl's fingertips and calico dress covered in blood, her fingernails ripped to shreds. On her frozen face was an expression of deepest horror: she had awakened from her coma only to be suffocated by the earth." Housebound ripples with such gristly horror, precise in its imagery and close to our deepest oneiric anxieties, the things older children deliberately use to terrify their younger siblings. We are mesmerized by Maggie's coming disaster, her awakening out of unconsciousness into what must surely be an even worse state. At last the children invade a secret room that they had all in some sense known existed behind the walls of the house. This climactic scene is simultaneously dreamlike, something out of a classic fairy tale, a Freudian representation of the unconscious, and a post-traumatic flashback to an earlier violence. Gentry's brilliance lies in the way a single scene can belong to different genres, all in play at once. The anxiety dream has its own outlines, which is not quite the same as the Freudian scene of repression. The ghoulish fairy tale chills but also consoles in that we know it's a fantasy, while the reenacted violence of the traumatized mind is real, tawdry, and claims its victim over and over again.

While Housebound might easily pass as YA fiction, most of its action limited to the world of the teenager, it's more than that, deliberately playing with that limit and transcending it. It ends with hopefulness, with mysteries resolved, but my mind turns back to the middle of the book, when out of nowhere Maggie sees herself dressed as a mermaid being propelled by unseen hands. Gentry lets that image loft through the dark for a hundred pages before we see it from a different angle. The suspension of resolution is skillfully crafted, where the blur, the shadow, and the fingers over the eyes hinder vision, and yet we know we are moving through a beautiful nightmare.