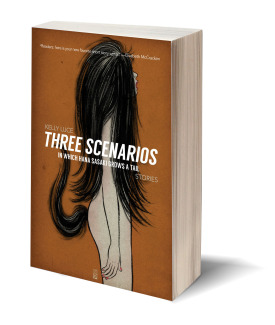

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail

By Kelly Luce

A Strange Object |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Lindsey Hauck

"Here's a story: two people are in trouble and the wrong one dies. There's been a cosmic mix-up, but there's nothing anyone can do about it, and they all live sadly ever after. The end."

Rather than an ending or a beginning, this passage, at once smartly economical and tragic, appears in the middle of Kelly Luce's debut collection, Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail. It's in a story called "Rooey," about a young woman, Maxine, who becomes obsessed with the tragic death of her brother Rooey and the idea that she should have been the one to die instead. "Rooey" is brutally honest, not only about pain, but about how our perspectives can change drastically in the wake of a tragedy. Maxine's attempts to navigate her world without Rooey and to keep a connection with him are clumsy but real: she masturbates in his bed and re-tells his favorite jokes at inappropriate times. She wears his clothes, sees (or imagines) his girlfriend, and examines the contents of his room until she finds she's literally become a different person.

"Rooey" is very different from the rest of Luce's collection in that it lays bare the internal world of a character much more starkly than the other stories do. Not that the rest of the collection is disconnected from experience; it glitters with hope and thrums with compassion. But being in Luce's world for hours on end had me fighting the urge to look over my shoulder. There's some benevolent but mischievous force behind these stories that takes them, and us, in unexpected directions.

Cosmic mix-ups like Maxine's run rampant here. Bodies change, past and present blur together, and everyday objects are endowed with unbelievable powers. These objects gleam with significance, standing in sharp contrast to the variety of blurry, blue-gray backgrounds that are both specific and universal. "Mrs. Yamada's Toaster," the first story in the collection, concerns a toaster endowed with the power to tell its user how they will die. When we first encounter it, we see Mrs. Yamada, a frail elderly woman described by the narrator as "a real religious nut," carrying it under her arm at the market, "its cord swinging beneath like a tail," as she tells a gathered crowd about its powers. As if the toaster weren't enough, there's also Mrs. Yamada's standing order at the liquor store for eight one-liter bottles of beer each week. The curious and kind young narrator, her deliveryman, imagines how Mrs Yamada might consume all that beer:

I thought of her at her impeccable kitchen table, pouring the beer into a glass and waiting patiently for it to settle, then taking the tiniest sip. I pictured her melting at the first drop of bitter liquid in her throat, her creamy makeup running down her neck, pooling between her breasts and in her belly button, and the starch on her collar drooping until her whole body oozed into a peach-scented puddle of foam.

Luce unravels each mystery—the toaster, the beer, and Mrs. Yamada herself—with delight and precision. It's a truly lovely story, and it sets the stage for the veritable parade of objects that follows in the rest of the collection. There are fountains which connect with the dead, an ominously leaky toilet, and even a virtual sea on the screen of a karaoke machine which, despite its intangibility, left me wondering whether it too had caused a drowning death.

Even though things are sometimes gray, spooky, or uncanny in Luce's world, it is also full of poignant moments of compromise and sacrifice, characters who put the people they love ahead of themselves and, as far as we can tell, won't be rewarded for it. In "Ash," a story which begins with a volcanic eruption described as a "hiccup," the narrator is briefly jailed and, upon her return home, can no longer hide her dissatisfaction with having put her career on hold to relocate to Japan for her husband's sake. After reciting the required lines to reassure him—"We made this decision as a family"—she feigns arousal until he falls asleep. And then, this striking moment: "The window was still thinly coated with ash, and I stared at it, scarcely breathing, loneliness on me like a glove." In the end, there is no dramatic escape, no rash divorce. Life goes on, the couple returns home, the narrator's career picks back up where it left off, and she remembers her time in Japan as she imagines her young son might: "once yellow ash had buried the city, and then things were kind of strange, and then they were OK, again." It's these moments of clarity that keep Luce's stories rooted in reality, even as they dive head-first into a sea of supernatural possibility. There is a warmly beating hopeful heart in each story, and it keeps on.

Despite all of the strangeness, the unexpected objects, and the aloof, sometimes bizarre, characters, there is an airtight internal logic to the world of these stories. They abide by the same rules, and they are consistent in their own breaking of those rules. Luce's voice throughout the collection is wonderfully imaginative and strong. She is the benevolent, mischievous force behind each story. And it's a force to be reckoned with.