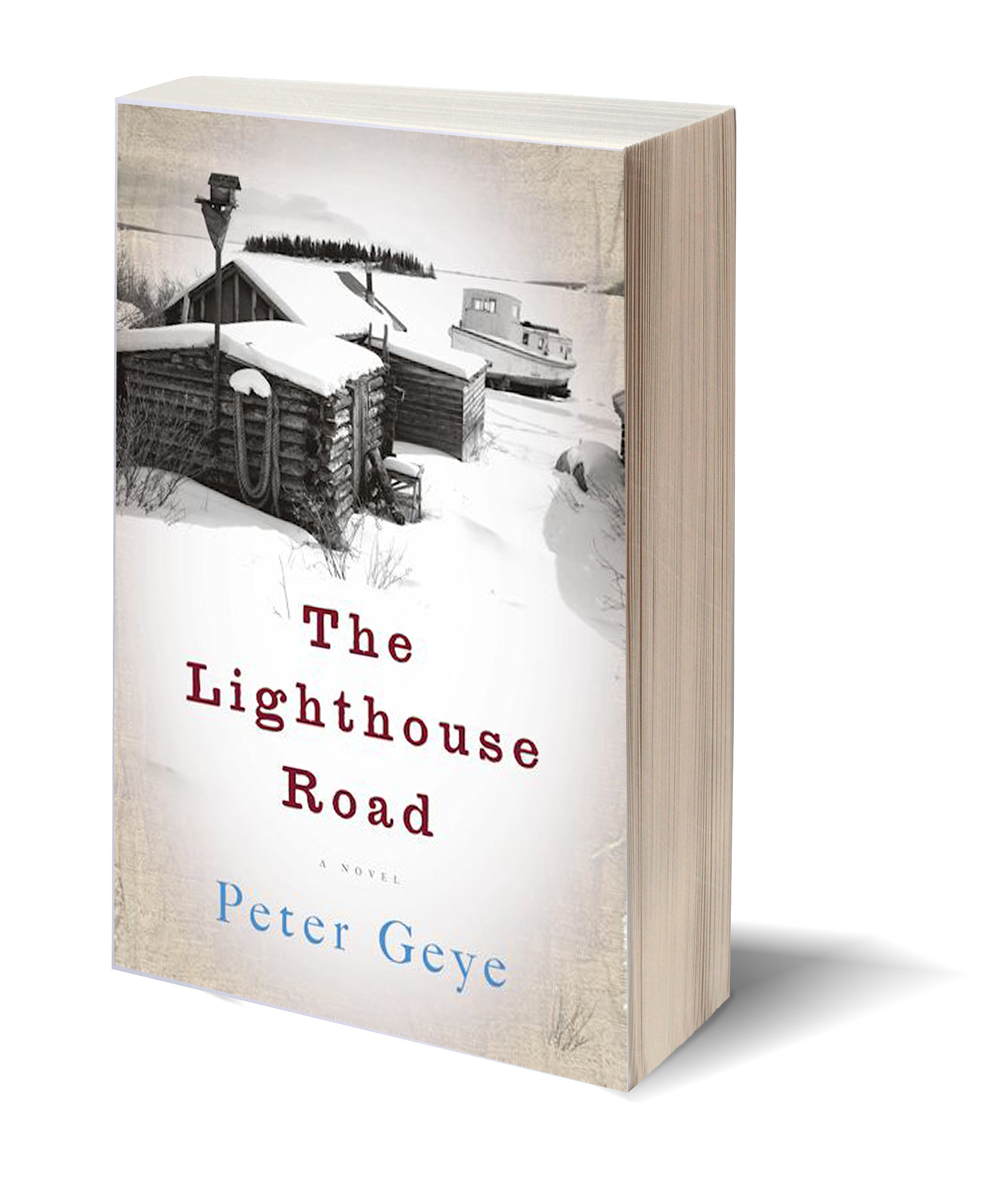

The Lighthouse RoadBy Peter Geye

Unbridled Books |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Jarret Middleton

Thea, a young Norwegian immigrant, braves the arduous Atlantic passage on the tri-masted steamship Thingvalla to begin a new life in the rough and miserly camp of Gunflint, Minnesota. Her emigration grows more foreign, solitary, and sweetly melancholic as each year passes. Gunflint is populated with rough and cold-beaten laborers whom Thea ends up serving as the camp's cook. Sportsmen, hunters, salesmen, and criminals all sift through their midst. She gives birth at the outset of one thunderously cold winter and we skip forward to the budding adult life of her son, Odd, gaining both separation from Thea and a darkened sense of entropy.

Odd is engaged in a struggle to gain independence from the father figure woven into every facet of his life, his employer, benefactor, and ultimate authority, Hosea Grimm. Out in the open, Grimm operates a local apothecary. In secret, he is the owner of The Shivering Timber, "an unabashed brothel and whiskey parlor that had evaded the reach of the pious Gunflinters and constables by catering to their weird and secret proclivities. It housed a dozen or so prostitutes and was guarded by two woodsmen brothers from Wisconsin on Grimm's payroll." On this side of his dirty business, he pays Odd to run barrels of whiskey in his boat up and down the lake.

As if his origins and relationship with Grimm weren't confusing enough, Odd falls in love with Grimm's daughter, Rebekah, and the two make a daring plan to escape Gunflint as the next winter approaches. Their stay in Duluth is sweet but short-lived. The distance from Grimm and the absence of all familiar surroundings reveals the ugliness lurking beneath Rebekah's mysterious façade. When Rebekah reaches out to Grimm in a letter, it violently reopens a rift that Odd could never again cross. After she leaves Duluth, Odd befriends yet another father figure in the boat builder Harold Sargent, who is impressed that Odd built the boat he arrived in from Gunflint. Harold is a hard-working, kind-hearted Christian concerned only with Odd's welfare. Clearly, he is not Grimm, and his attentive care and employment sets Odd on his course to become a lifelong boat builder himself as, eventually, he makes his fateful return to Gunflint.

While the plot is certainly moved by the past's shaping of us and our burning desire to leave it behind, winter is an infinite presence that elevates out of the role of central metaphor and into the perplexing movement of character. Nearly every chapter or section opens with natural phenomena, as though the characters are vital extensions of the energy and essential earthy forms that sustain us. When a felon speaks to a full courtroom at his trial, he has no recourse but to blame it for his crimes:

"I took the Minnesota camps. Me and that old mare with the suspect hooves. A goddamn sleigh and a map and that winter enough to freeze a man's reason right out of his head." He paused, ventured a look in the judge's direction. "That's what I mean. You all felt that cold. Colder than this world was ever meant to be."

The winter is a pattern of conditions that forces everything subjected to it to die and that which remains must shed itself of everything but necessity in order to survive. The very essence of the cold gets into the characters through each of their cardinal weaknesses. This magnificent, powerful force that surrounds us from outside begins to grow from within and requires each character to make an integral sacrifice. In essence, the characters become winter so that they can live through it. This is what the criminal clung to in his defense, and it is what is found at the center of Odd's labor, Rebekah's doubt, Grimm's control, and Thea's pure-hearted yearning toward God.

The epoch of the American frontier at the turn of the 20th century is framed by the harsh landscape, the sacrifices of its settlers, and the common occurrences of brutality among them. In between running whiskey and plotting to flee the camp, an adventuring Odd loses one of his eyes upon peering into a bear den uninvited. A ferocious fight erupts between a pack of wolves caught dismembering a fallen horse in the night and the massive St. Bernhards that guard Gunflint. The prose style of these and other action scenes is a clear evocation of historically accurate place and local speech whose musical movements effectively deliver the gravity of each consequence.

On February twelfth one of the great horses was killed on the ice road, crushed by a careening load of timber. In the same mishap a teamster lost a hand. Soon after one of the crews had a man beheaded on the northern parcel and two days later one of the sawyers passed through camp minus a leg. These were known hazards, though, and the general comportment of the men in the shadows of such calamities was not much changed.

Geye zeroes the reader into the mysterious persistence of the plants, animals, and people that make it through the natural cycle of death each winter imposes. The ethos of what is required to survive the cold in their surroundings and in themselves gives this beautiful cast of characters their chance at life.