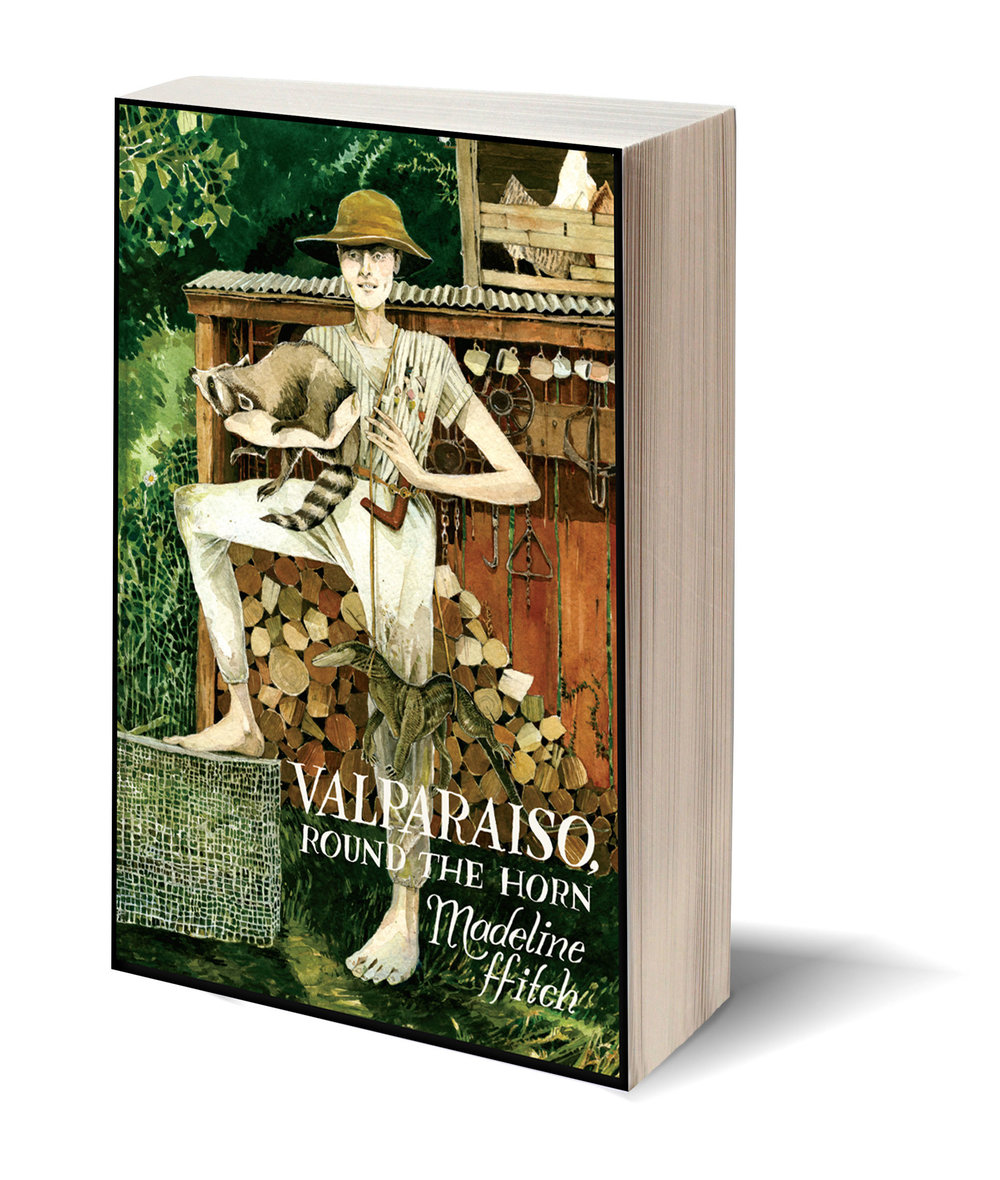

Valparaiso, Round the Horn

By Madeline ffitch

Publishing Genius |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Lindsay Hauck

The various worlds in Madeline ffitch's first short story collection, Valparaiso, Round the Horn, are incredibly, immensely full, though many of her characters live in highly isolated places. We encounter lost and abandoned children, tragic accidents that leave victims mutilated, the Black Panther Party then and now, long-lost twins, apocalyptic meteors, and the strange dynamics of rural life. One character, a young writer named Yancy, at one point vows to write stories with "more shooting off of guns than ever before, except for those certain stories that began and ended quietly, that were written fervent and feminine as snow." This seems to be ffitch's ethos as well, guns and all. These stories are full of people who tend to state what they want, though sometimes abstractly. And they tend to get it, but not the way they planned.

These worlds are peculiarly American, in a way that most of us have forgotten to think about America, as a place full of frontiers and the righteous lawlessness of nature. One of the most unique and refreshing aspects of this collection is the way ffitch manages to interweave the human world and the wild, animal world. In "The Storm Beach," Edmond returns from Seattle to the coastal island where he grew up. He's on a mission to carry out his dead grandfather's last wish to have his body set ablaze on the beach. This is a goal that Edmond admits is not technically legal, and certainly wouldn't be possible on the mainland, but the island is his frontier, and its freedom comes with complications. After Edmond manages to haul his grandfather's slack body down to the ocean, he works by moonlight to gather kindling for the funeral pyre. As he works, momentarily distracted, the tide rises until his grandfather becomes half submerged in water. "Green crabs struggled along Granddad's shoulders and crept over his face, pulling at his Pendleton shirt, nibbling at the scratchy skin where he stopped shaving. Cursing, I plunged into the water, brandishing a club of driftwood, and I beat my Granddad's body until all the crabs were gone." The story continues this way, with everything going wrong that possibly could, but no setback can dissuade Edmond from what he knows he has to do, not even the sea itself.

In the final story of the collection, ffitch recalls an America obsessed with its own largeness of land and fauna, a place bursting with possibility; an America that invented Paul Bunyan, a character finally big enough to occupy its vastness. In "The Big Woman," a man named Marcus, a construction worker, wants a wife. A big woman, who will appreciate what he's begun to build: not exactly a homestead, but a piece of land with a trailer, a trampoline, and a mysteriously disappeared goat. It is his attempt at the American dream. Then, one night, a big woman arrives.

He saw her appear out of the darkness at the edge of the woods, flickering through the last line of ash trees. She blended momentarily with a sycamore. She separated from it, emerged into the meadow. The big woman had his dead goat yoked around her shoulders and it bled down her front . . . She was one of the biggest women Marcus had ever seen. She carried the goat up to his trailer. Marcus spit on his hands, rubbed his face to redden his cheeks, smoothed his hair, opened the door.

Once again, someone gets precisely what they desired, but this time, the complication comes not from interfering natural forces, but from another character: the thief who lives across the street, who's already in love with the big woman. Even in the stories that ffitch begins and ends more quietly, there is no lack of conflict. The stories are not atmospheric nature narratives. They are small but powerful epics of adventure.

The title story is about another construction worker, a shy man named Abie Carlebach, who dreams of "[hopping] on a steel plank being lowered to the ground by crane. Also, to mimic the photo of the construction workers lunching on a crossbeam while building the Rockefeller Center." While Abie doesn't exactly do any of those things, he does find a way to break free of his own limited expectations of himself. He follows a local chanty-singing captain out to sea, to Valparaiso, "round the horn." He falls in love. He does not return.

Another hasty but rewarding escape happens in "Fort Clatsop," though this time out of desperate panic. A father, Frank, makes a hidden home for himself and his daughter Huck in the boiler room of the school where she is a student and he is the janitor. He makes extra money by stealing unused equipment—musical instruments, projectors—from the school's basement and selling it at pawn shops. Eventually, their secret is revealed to Huck's classmates and teacher. There is a moment of panic, but the answer is clear: they have to run. In fact, they'd been looking for a chance to run headlong into the kind of home they really want, and this is it. As they take off, Huck tells her dad:

The boiler room, the oboes and aquariums, the pawn shop. Those are not part of our mission. Living that way is only evasion, and it's imaginable to the plain people. It's a form of resistance they can understand and eradicate. They can laugh at it. They can catch you. It's small time. It's a compromise where there can be no compromise. What is left to us? To live in such a luminous way that anyone who tries to trace us is blinded.

This kind of dialogue, which tends to run long and lands like poetry, is sprinkled throughout the collection. Characters' voices often sound more like the voice of a writer than the voice of a person, but ffitch uses this liberty wisely. By employing a more omniscient voice, she is able to restore order to a sometimes anarchic world. It also feels appropriate considering the way her characters tend to go brazenly after what they want. The beauty and clarity of the language makes this feel possible, for them and for us. Valparaiso appeals to our deepest desires (love, family, adventure) and fears (aloneness, the end of the world as we know it), but it's really the exquisite composition of each sentence within that makes it a joy and a thrill to read.