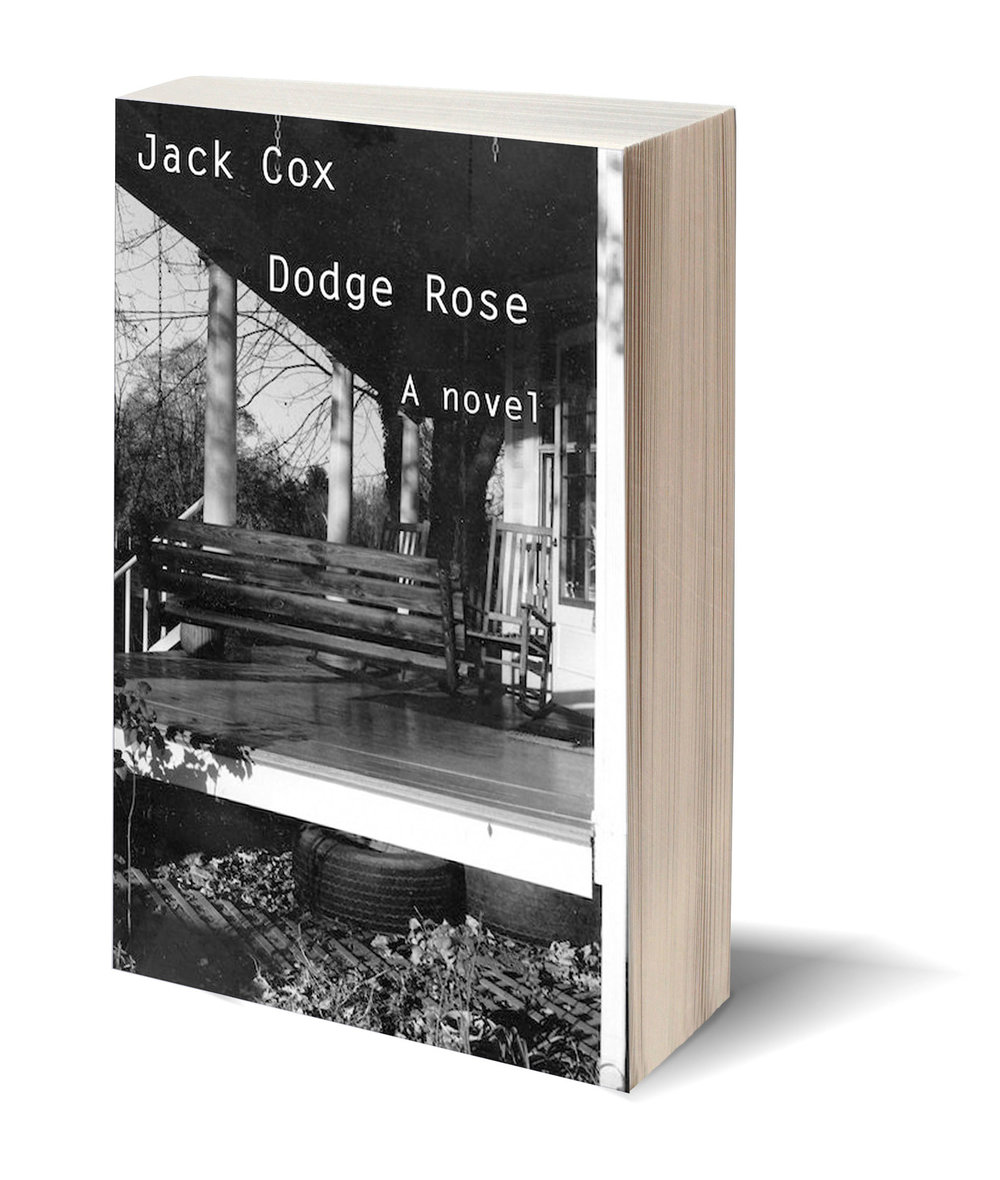

Dodge Rose

By Jack Cox

Dalkey Archive |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Jacob Singer

Dodge Rose, Jack Cox's debut novel, is a compact and innovative exploration of the relationship between a family and their things. Cox offers a simple premise that quickly unravels into something more complex. The story follows Eliza and Maxine, long-lost cousins, as they attempt to execute the estate of Dodge Rose, Eliza's aunt and a mother figure for Maxine. Both women, who are in their twenties, desire to take whatever money they can get from the liquidation and move forward with their lives. But with each step, their initial optimism dwindles.

Stylistically, the book shifts among the minimalism one might associate with Samuel Beckett, the legalese of William Gaddis's A Frolic of His Own, and a blend of British modernists. While stylistically innovative, Cox structures the first half to fall like dominoes. One of the first plot twists is that Maxine, raised by Dodge, doesn't have a birth certificate or adoption papers. This creates a legal quagmire. With those documents Maxine would get everything; without them, nothing. So the cousins visit Dodge's lawyer, who can't find any of the family's paperwork. The lawyer says they can go to the state but that it could take years. The predicament worsens. Neither has the energy or time to work within the broken legal system, so they take matters into their own hands and agree to liquidate everything and split the proceeds.

They both look into selling the apartment only to discover that Rose was an "archaic" renter, a blow to their payout fantasy; in fact they owe rent. The next step is to sell her belongings, but that comes with its own set of complications. Every step of the way, the two get a better understanding of their predicament and find a way to move forward in executing the will.

One of the more interesting features of Dodge Rose is that Maxine seems to have uncommon access to Eliza's experiences, though it takes a few pages for the reader to gather enough textual evidence to figure out Cox's use of point of view. It feels omniscient because of the level of detail provided. But there is a specific first person narrator who says in the second paragraph, "I wrote the other letter." On the following page, the narrator says, "We were twenty one and halfway into 1982." This hints that Maxine is the narrator but it is still a bit unclear. Later Maxine notes, "Hello Eliza I said. Make yourself at home." In this dialogue, which lacks quotation marks, the reader become clear who possesses the narrative "I." While it can be slightly dizzying, it also results in a form of estrangement that engages the reader. One must constantly wonder how Maxine has such complete access to Eliza's thoughts, something present at the very opening of this book. Here is the opening paragraph that breaks traditional laws of realism and punctuation.

Then where from here. When the train rolled over a canopied bridge the eyes of the boy in the opposite seat opened and closed to the broken sun but he dozed on. His head was rocked against a woolen sleeve. Eliza had stretched her legs out in the space beneath his feet and now she crossed them and pressed her thumbs to the bundle in her lap.

Maxine couldn't know that the boy's head rocked against his woolen sleeve. This language breaks the laws of common sense, but its richness toys with a more omniscient point of view, one that creates a verisimilitude that attracts the reader. The opening sentence's lack of a question mark forces the reader to slow down, look again, and re-read.

Halfway through the book the story abruptly shifts to the booming economic optimism of the 1920s, a sharp contrast to the desperation felt by Eliza and Maxine during the 1980s. If the first half of Dodge Rose is about the liquidation of belongings, the second half is about accumulation. This part of the book follows Dodge Rose as a young girl as she and her family settle in to the apartment.

The reader can't miss this narrative pivot because of the shift in language, which becomes something similar to Joyce at his most dreamlike: fragmented, phonetic, and playful. Cox indicates that Dodge might have cognitive limitations, which would explain his stylistic manipulation. A single word might constitute an entire sentence, the punctuation can be slapdash, and the focus might dissolve from language to sound, creating something idiosyncratic.

e n o w i said. wide. woops. there goes monday. open. cell whats this made of. bumwool. in my. like a flick. a gen lick. peepers. orgen. molten. before.

But Cox is well aware that this can't sustain a novel. These sections ebb and flow with a more traditional use of interior monologue. While he never offers the reader the complete picture of the Rose family, the reader gets glimmers that hint at connections between the first and second half. This points to the fascinating structure of the book. The story moves backwards from the '80s to the '20s, a dead woman becomes a young girl, and sold possessions are accumulated. It reads like an M. C. Escher drawing.

Before the story begins, there is an unattributed quote: "Revenge is a wild kind of justice." The quote is from Francis Bacon's essay "On Revenge," which deals with the idea that the desire for revenge is a natural emotional response, but that legal systems, on some level, exist to keep humans' savage nature in check. One must use what is publically sanctioned by the state: the law. But that is conditional upon a working legal system. What if that system is broken? What if the lawyer lost the papers? What if it will take years to find a birth certificate? Maybe then, if the conditions are right, one can justifiably take matters into her own hands and become a vigilante. And maybe that is just what Eliza and Maxine become in Dodge Rose.