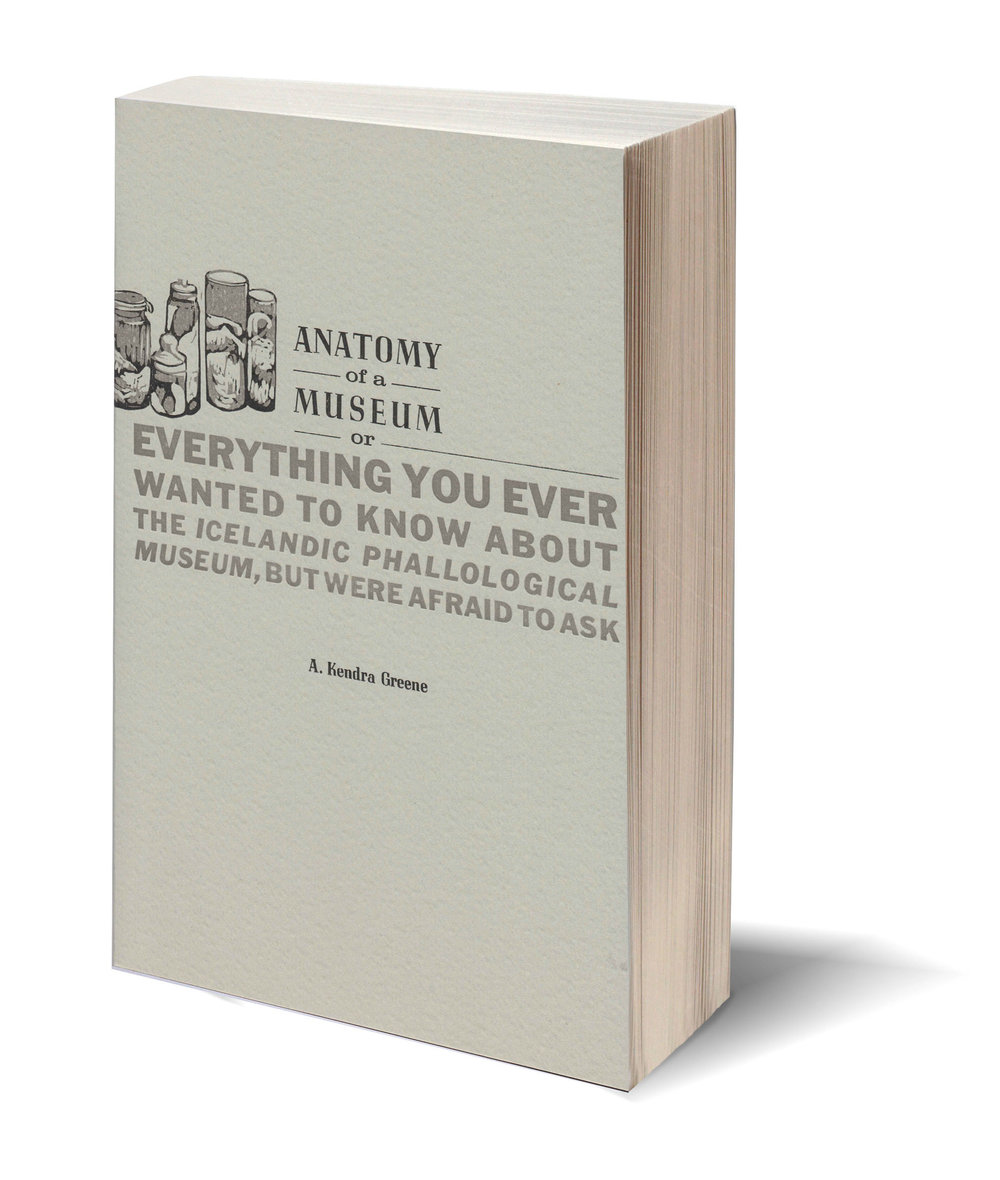

Anatomy of a Museum

By A Kendra Greene

Anomalous Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Hannah Abegg-Verk

When I first read the title of A. Kendra Greene's essay collection, Anatomy of a Museum, penises were far from my mind. That is, until I read the alternate title: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about the Icelandic Phallological Museum, but Were Afraid to Ask. It took me a second; I sounded it out: phall-o-log-i-cal. So, a book about a penis museum. OK.

Greene's essay captures the oddity and uniqueness you would expect from a book like this. However, she also does something notably fascinating by juxtaposing the absurdity of a penis museum with the mundane quality and everydayness of the penis itself, despite the historical tendency to figuratively (and literally, in the case of Iceland's museum) put the phallus on a pedestal.

Anatomy of a Museum is small—smaller than I expected. Which is good, I'd say. In quick paragraphs flashing articulate images of penises large, small, and invisible, Greene manages to detail (in 39 pages) a tour of the small museum, which opened in 1997 with only 62 specimens. Now, 212 specimens occupy the domestic collection, and 64 reside in the foreign and folkloric section. She reveals, "There are dragonflies with phalluses" and that a "duck's penis is a corkscrewing tentacle of an organ that unfurls to a length equal to that of the duck's whole body." But Greene says, "yet, still, it's a little overwhelming." When she first walks in, she sees a half-naked man. She then notices the museum is partly lit with scrotum-skin lamps (available for purchase in the gift shop, by the way). There are duck penises, hamster penises, whale penises, human penises, and penises from folklore. It continues: there are tiny penis bones, large penis bones, silicone-filled penises, aged and shriveled penises, hairy penises, and penises weighing in around 60 pounds. Penises . . . everywhere.

Surprisingly, Greene writes, "frankly, it's not all that odd a place." She describes the museum, sometimes, with deep respect because the curator, Sigurður Hjartarson, and his family work hard to keep the place afloat. Yes, it's a family affair. The curator's daughters have even contributed artwork to the folkloric collection, and they work to procure new specimens. His son will inherit the museum whenever the time comes. But Greene also discusses the place exactly as one might be expected to discuss a museum full of penises: lightheartedly and with a sprinkling of jokes. She admits, "There's no helping it. No matter how erudite or how innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. And eventually, you will—you must—surrender to its charms." And about the penis jokes, "they will get harder and harder to resist. Your friends will insert them everywhere. They'll become a handful." Funny, right?

In the end, Greene's voice is what kept me reading. About penises, I had little interest, but Greene has a way of pulling you along with her, through the hallways and alcoves, exploring mammal, marsupial, and avian species. Anatomy is split into two sections, one separated from the other by monochromatic cartoonish renderings of some of the specimens. One has the appearance (to me) of a microscopic organism propelled by cilia. Another requires a large magnifying glass to observe. The last looks like a little forest of human penises kept in an aquarium.

While the first section deals with much of what lives in the museum and who visits, the second section stays with Hjartarson, his family, and the ideas of what the museum represents. For example, even during the museum's off-season, Hjartarson posts a note on the door with his personal phone number, offering appointments for the "very eager." And he has a favorite section: the folkloric. Even his daughter, Lilja, remarks that "some feminists like the museum because it takes the phallus off its pedestal: shows it as just another thing in the world, stripped of its mystique. Which is fascinating, given that the specimens quite literally are on pedestals—some of them, anyway."

Which leads Greene into what she's been getting at this whole time: "More broadly, it is a museum of language, of expectation." When we read penis museum, we think certain thoughts—but to that, Greene says, "It's sort of an embarrassing disconnect. How shabby of us, in the bluster of association and innuendo, to have constantly invoked the word while stubbornly neglecting to consider the plain bald fact of its fat and flesh and skin." It's not just a penis museum: "This is a museum of substance." Here, you won't find what you expect. The Icelandic Phallological Museum is a sober destination in a world where bachelorette parties throw penis confetti and drink from penis-shaped straws to celebrate an impending marriage (and they'll visit the museum, giggle together, and take photos beside the whale specimens). Greene says, "You arrive prepared to be shocked, but it turns out what's startling is that someone has dared dedicate a museum to something so very common—the penis not presented as vulgar but as ordinary."

And why not the vagina, you ask? The curator will tell you, "with the wink of a man married some fifty years, 'Women, in all things are more complicated than men.'"

In the end, Greene successfully gives significance to this strange and lovely place. It somehow nullifies power where power has so long been present, but it also embraces the novelty, oddity, and sexuality in nature. Through clean and engrossing prose about family, culture, nature, and animals, Anatomy of a Museum satisfies that urge for new information, but does so with feeling. Greene writes, "novelty itself is a museum tradition . . . Museums were born of novelty. They specialize in it. And furthermore, they do it well. But some, the Phallological Museum reminds me, do it better than others."

So now, every time I think of worthwhile museums, I'll think of penises. I'll think of Anatomy of a Museum, and I'll recommend it when someone brings up museums. And when that someone asks, "What did you say?" I'll sound it out for them, too, so they can stop and re-think: "Phall-o-log-i-cal."