Blood in the AsphaltBy Jesse Sensibar

Tolsun Books |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Emily Hoover

Think back to every car accident you have ever experienced as a driver, passenger, or witness. Imagine the sound of tires squealing against pock-marked, frost-lined asphalt and a cacophony of horn honking, yelling, and hushed tears; picture brake lights flashing, smashed bumpers, and shattered glass; visualize motorists talking on cell phones with insurance people, rubberneckers surveying the damage from the comfort of their own vehicles, and first responders, surrounded by emergency lights, tending to the injured. Something that is probably missing from that scene is the tow truck driver, but rest assured he is there, and whether you saw him or not, know for certain that he "turned on the upper work lights, dropped his bed, attached his chains, and engaged the winch," slowly dragging whatever was left of the vehicles involved onto the bed of his truck without being prompted, thanked, or remembered later.

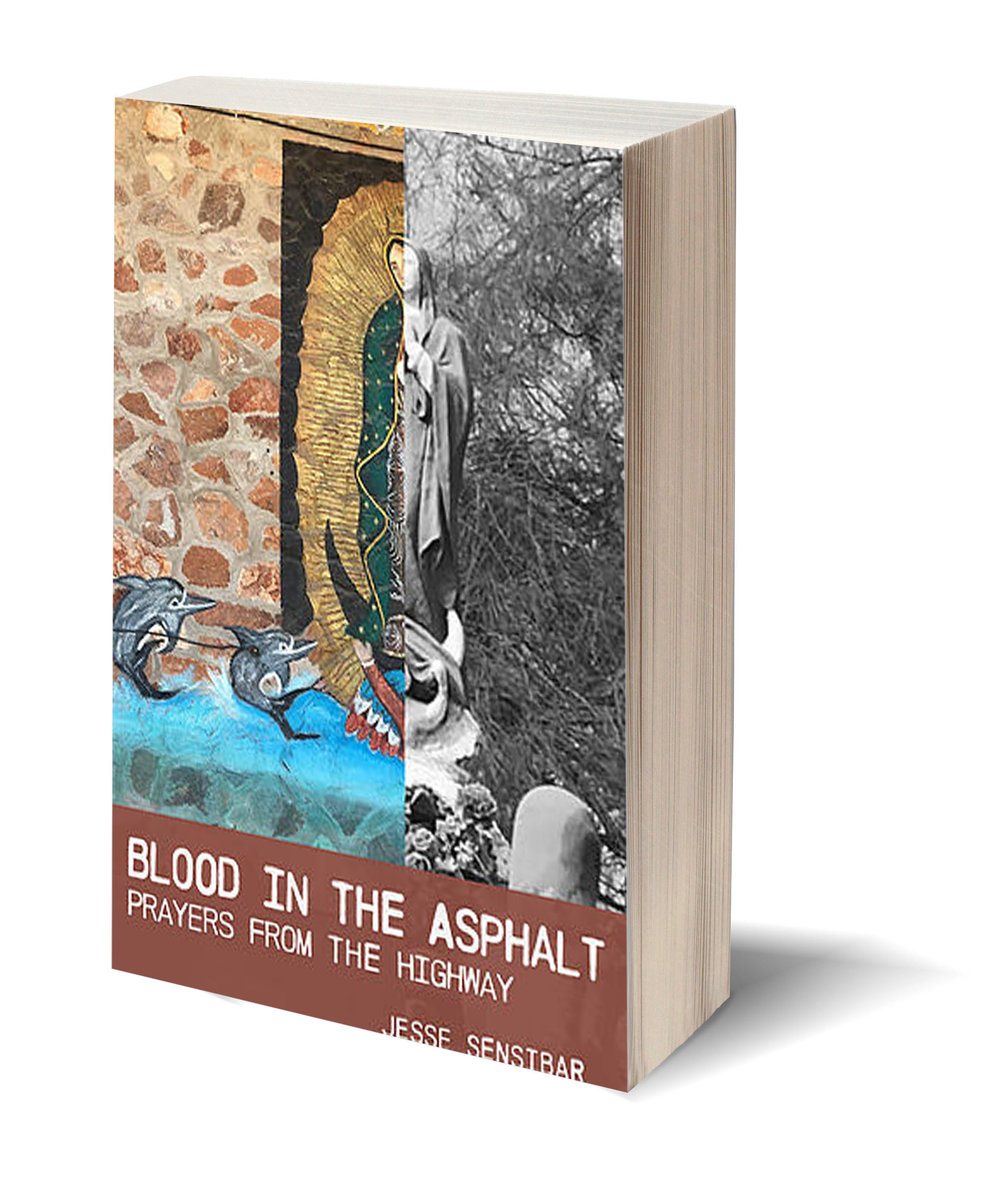

Jesse Sensibar, author of Blood in the Asphalt: Prayers from the Highway, knows what it's like to arrive at the scene of an accident or breakdown and take action because he wrote the quoted lines above. As he says in the story "Windshield Time," "I was a tow truck driver out of Flagstaff, the small mountain town in Northern Arizona . . . The stories I can tell about those years of my life go on for as long as the highway itself, all the way to the sea and then back." In this book, released this October by Tolsun Books, a small press in Arizona, he divulges some of these stories—as flash narratives and also as poems that accompany highway photos of blue skies, desert dust, pick-up trucks, and shrines for the dearly departed.

Even though "Windshield Time" is the first piece in Blood in the Asphalt, the seeds it sows grow throughout the book. In this story, Sensibar establishes his ache for the road: "It still calls to me . . . to come and cry without a sound as I roll down the road. To come and feel. And most of all to come tell, to bear witness to all that the road has to offer. The Highway gives and the Highway takes away." Photos like "9 March 2018" reveal the latter. In Tucson, at the cross streets of Bellevue St. and Camilla Blvd., a shrine made for a child named Victor survives, enclosed by stuffed animals, flowers, books, and rocks. "These ones for the kids always gut me, no matter how many times I see them," Sensibar writes in the photo's caption, illustrating that his frankness is not callousness—only powerlessness. Later, in "4 November 2017," Sensibar writes of "Russell's shrine along the right-of-way fence" on I-10 Eastbound in Casa Grande, Arizona. "I'll pass this shrine twice today," he writes. "Once on my way west to the wedding of two young friends. Once on my way east toward the All Souls Procession. I'll celebrate both love and loss; beginnings and endings, give and take." In juxtaposing two extremes—a wedding and a Day of the Dead celebration—Sensibar asks readers to brake, to stop somewhere on the highway, somewhere between grief and excitement, and observe; observe the life that has been stolen by the road and the roadside crosses that remain.

Blood in the Asphalt is not concerned with a concrete timeline because chronology doesn't matter to the personified road, nor does it matter to death itself. The book bounces through time, from 2015 to 2018, in order to create the feeling of time as opposed to the linear truth of it. Anyone who has experienced loss can attest that it's breathless, blurry, and jarring no matter how much time has passed. "18 September 2017" tells of a makeshift shrine composed of "Ford truck emblems, a motorcycle tire and wheel, and two connecting rods with pistons attached" located off US 160 in the Navajo Nation. While the photo is bright, with patches of sun highlighting rocks and fresh flowers that encircle the shrine, Sensibar notices that there is a framed photograph that "has been all but taken by the sun" and also a white ammo tin containing a notepad with a message on it reading, "Well, it's been six years now." The sun's rays serve as an ever-present reminder of all that time has eroded, and instead of weighing in on what he observes, Sensibar just notices and reports the facts, creating space for the reader to mourn quietly. Similarly, "5 January 2017" features a photo of a shrine near the Cornville, Arizona, rest stop off I-17. While the white cross bearing the deceased man's name stands out in the foreground of the image, in the background, an older cross "stands like the shadow of the new," cloaked by an overgrowing Sotol succulent. Close readers will see the person died in 2008, a decade ago. While coaxing readers to identify the passage of time via its mark on the land, Sensibar also asks us to consider the friends and family members also marked by a loved one's death.

A stand-out story in Blood in the Asphalt is called "The Lucky Shirt," and it appears about a quarter of the way through the book. It follows a tow truck driver who searches a dead man's 2007 Ford truck in search of the title; the caring tow truck driver, who we perceive as Sensibar himself, just wants the title to sell the truck, so he can pay the towing and storage bill and spare the family any more pain. In the truck, he finds an XXL-REG shirt that the dead man must have removed the day he died due to the warmth of his car's heater, and he decides to keep it. "Because I have seen so much, I know that [death] can and does happen to anyone . . . myself included. But now I have your shirt, and your shirt becomes my lucky shirt, because I know the chances of two people dying in the same shirt are slim indeed," he confesses. This story reveals Sensibar's own vulnerabilities, his own fear of death, which is a gift to readers moving through a book about loss and the impermanence of life.

Blood in the Asphalt is for anyone grieving—whether that person is grieving for someone gone too soon, for the changing landscape Sensibar calls "the disappearing west," for marginalized communities at the highway's edge, or for tow truck drivers everywhere, who are more like unrecognized saints.