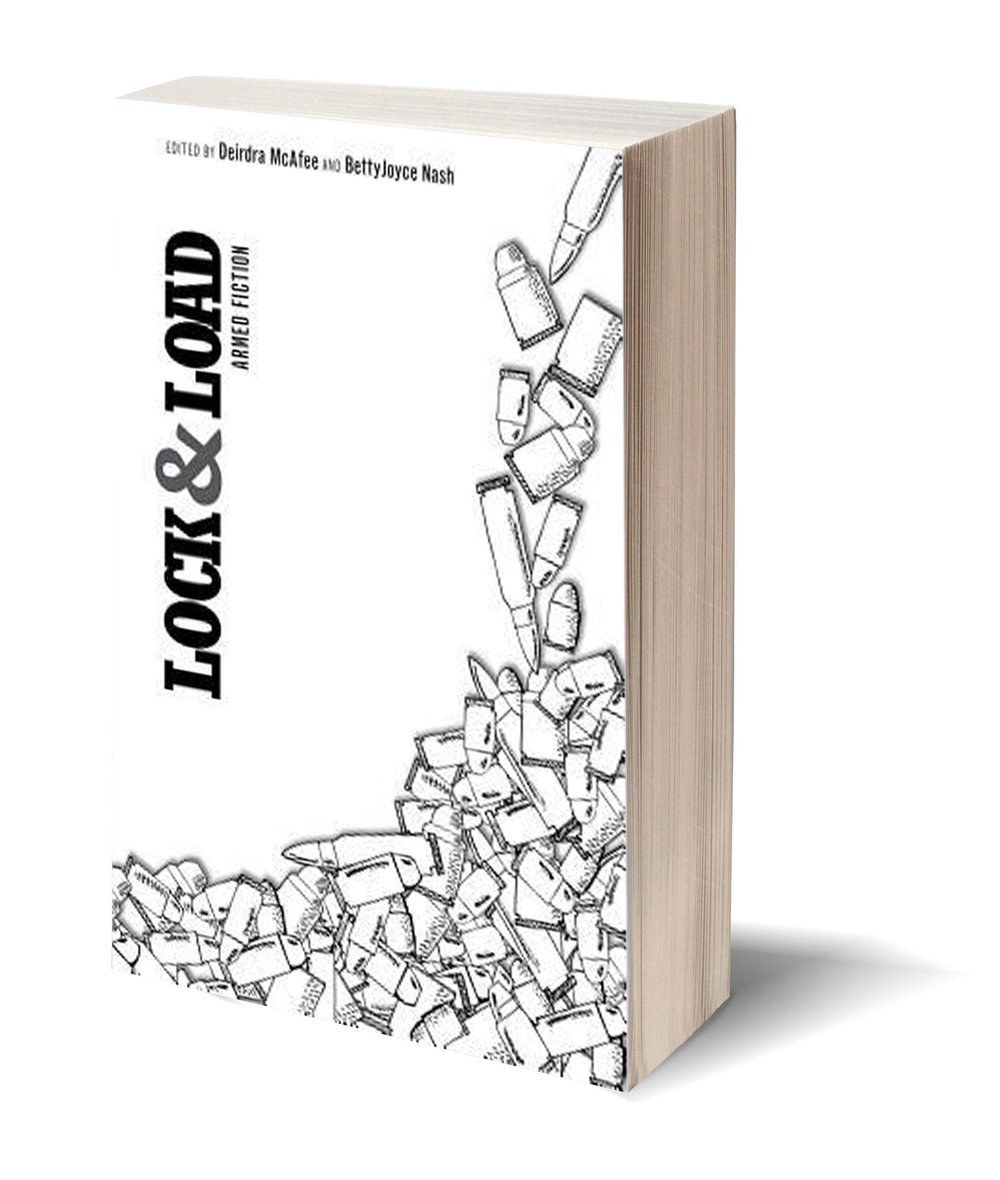

Lock and Load: Armed FictionEdited by Deirdre McAfee and BettyJoyce Nash

University of New Mexico Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by John David Harding

"Nothing says America louder than a gun." So begins the editors' preface to Lock and Load, a new collection of nineteen "armed" stories exploring a range of characters, situations, and themes. Each story makes mention of a gun, but firearms are rarely the central subject matter. Rather, these stories focus on characters whose lives are in some way shaped, impacted, or ended by firearms. Although guns serve as the connecting link between stories, the collection's variety makes them feel related but not repetitive. Indeed, the principle of Chekhov's gun—the idea that every detail in a story must have a purpose, that a gun introduced early on in a story must be fired by the end—is not universally enforced here, and the results are often surprising and satisfying. Far from formulaic, Lock and Load creates a tableau of an America riddled with bullet holes.

None of these stories encapsulates the gun's destructive power more masterfully than Annie Proulx's "A Lonely Coast." It is the story of Josanna Skiles, a Wyoming woman whose role in small-town imbroglios leads her into a precarious situation replete with high tragedy, the first of many scenes of bloodshed to follow. Set against a desolate Wyoming landscape that only Proulx could conjure up, the plot unspools little by little until it has utterly ensnared you. Admirers of Proulx's work will recognize her trademark style, namely her ability to capture time and place:

There's a feeling you get driving down to Casper at night from the north, and not only there, other places where you come through hours of darkness unrelieved by any lights except the crawling wink of some faraway ranch truck. You come down a grade and all at once the shining town lies below you, slung out like all western towns, and with the curved bulk of mountain behind it. The lights trail away to the east in a brief and stubby cluster of yellow that butts hard up against the dark.

Proulx thus invites readers into Josanna's world, and coaxes us at story's end to examine hard truths about what a person is capable of doing if given the opportunity.

A counterpoint to the unbridled violence at the end of "A Lonely Coast" is Jim Tomlinson's "The Accomplished Son," a story that breathes new life into fiction about war and revenge. Toby Polk, the titular character, returns to Kentucky after his third tour in Iraq to visit his recently deceased father's grave. The death was not unexpected: his father had been paralyzed years earlier in an accident, which might have been the result of another man's negligence. Alternating between scenes of Toby's childhood, his memories of the Iraq War, and the present moment wherein Toby mourns his father's death and grapples with exacting his revenge, Tomlinson weaves together a national narrative of war and Toby's struggle with his inner demons. One scene captures the melding of past and present as Toby gears up to avenge his father's death: "Dew soaks [Toby's] blue jeans. A shiver races up his back and across his chest. He remembers the heat of Baghdad, how he'd crave a chill like this as he lay waiting, helmeted, body armor zipped and snapped. He'd baste there in his own sweat drippings, eyes stinging, his M-24 sniper rifle braced and waiting for another kill." Toby's journey to reconcile not only his time in Iraq, but also the facts surrounding the accident that paralyzed his father, leads to a breathless conclusion in this heart-wrenching story of justice and mercy.

In contrast to the unflinching realism in "The Accomplished Son," Mari Alschuler's "Revealed" stands out for its presentation of an alternate reality in which gun ownership is not only legal, but compulsory. Citizens in Alschuler's version of New York City are required by law to openly carry a government-issued handgun. People over eighteen receive one bullet per day to use as they see fit. Now that everyone is packing heat, even the smallest public altercations lead to gun violence, as illustrated by scenes on the subway, where accidentally bumping into someone or taking their seat might result in a gun battle. But there are some, such as Sydney Simich, who save their bullets in case of an emergency. Sydney's tepid love life parallels her ineffectual career as an employee of the city's welfare system. In light of the new gun policy, her welfare cases have slowed to a crawl, not because poverty has been eradicated, but because the poor and the indigent were "picked off during the first few months of the new policy, dispatched by the trigger-happy as leeches or ingrates, worthless vermin, or lazy good-for-nothings." On its face, this scenario seems absurd, but Alschuler so clearly renders a society immune to gun violence and gore that her fiction doesn't seem too far beyond the realm of possibility.

Unfortunately, Alschuler's dystopic vision of a heavily-armed society is more allegorical than speculative. My time spent reading and rereading Lock and Load was bookended by two very real tragedies involving firearms. The first was a massacre at a church in Texas, where twenty-six people were summarily executed by a gunman with an automatic rifle. The second occurred more recently at a high school in Florida, where a former student killed seventeen people. In light of these events, I struggled to read this book without returning in my mind to the problem of gun control. In the collection's introduction, the editors write that Lock and Load "takes no political stance," a necessary disclaimer for a book that readers from across the political spectrum might approach with trepidation. Fear not: these stories never directly engage in outright political dogmatism, nor do they take the form of ham-handed parables on the dangers of guns. But even though these compelling stories do not adopt a particular political stance per se, all of this violence, all of these shattered lives, in these stories and in the real world, make it increasingly difficult to ignore their common denominator.