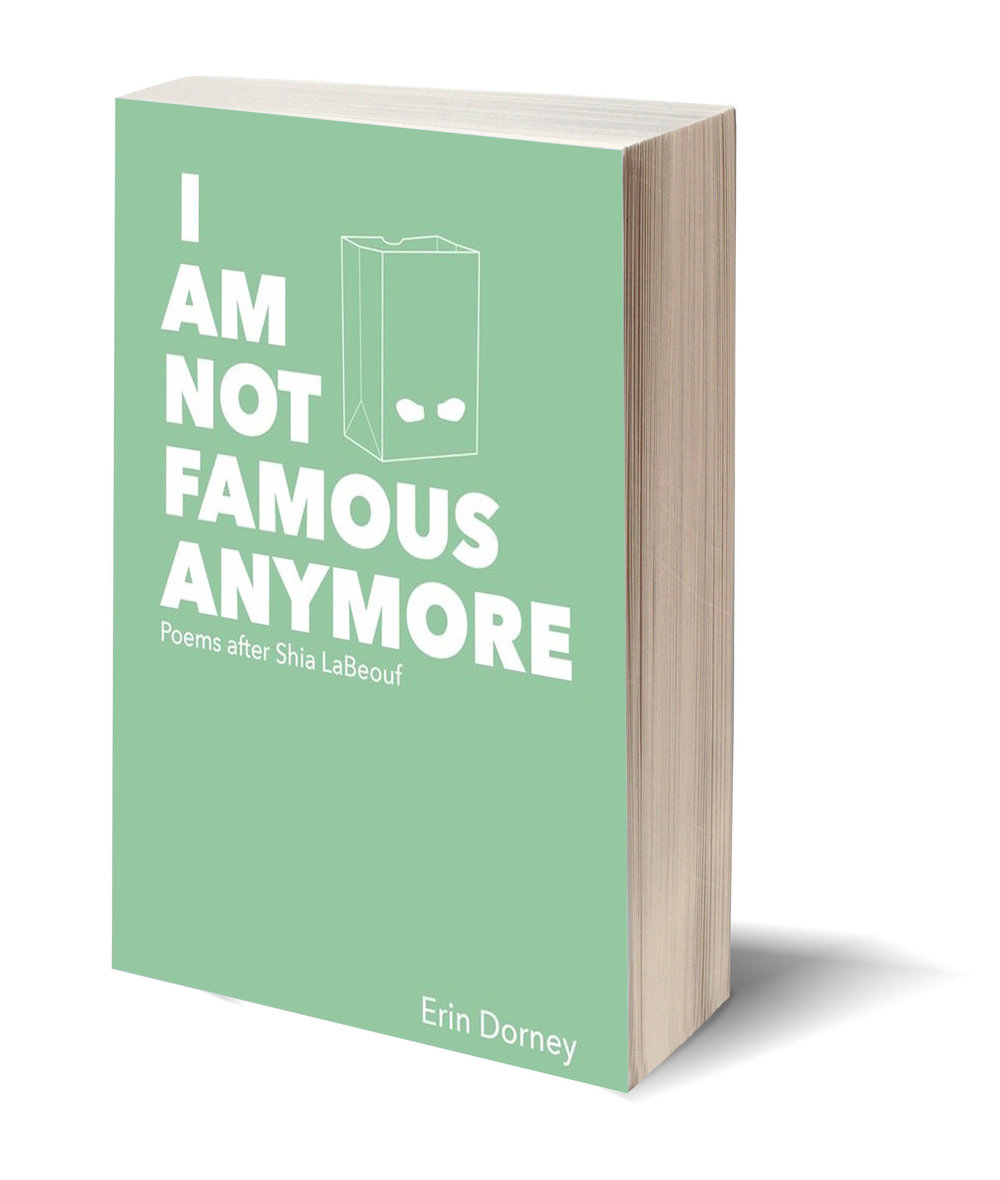

I Am Not Famous AnymoreBy Erin Dorney

Mason Jar Press |

|

|---|

Reviewed by Jessica Hudgins

In her new collection I Am Not Famous Anymore, which carries the subtitle, "Poems after Shia LaBeouf," Erin Dorney writes erasure poems culled from interviews with the actor. Dorney's poems are accompanied on the page by the interview she pulled them from, and they're generally in the first-person, generally from the point of view of a speaker we assume is Shia LaBeouf.

At first read, I was tempted to go back to the original interviews and flip back and forth to understand the poems' source material and, maybe, to understand a little bit about Dorney's process. As I read on, however, I become more aware of Dorney's voice, which materializes within and beneath LaBeouf's. This dynamic, where LaBeouf's language is transposed over the course of seventy pages into Dorney's, is incredibly fascinating. It's also well-matched to the form of erasure.

Even though most of Dorney's poems are in the first-person, they begin, with the third and fourth poems in the collection, to open up and out. The use of the first-person plural, "It's Not a Birth / we were invited to be a part of," gives the poems a more universal scope, involving us in the story Dorney's writing, while the third poem's use of the third person, "They fell in love / with that slow progression," begins telling a story which both the readers and the teller (presumably) are external to.

The next poem, "I Am," is from the point of view of a paper bag:

Not permanent—

I was folded.

I was made to hold things

and on the way home he cut me.

Now I am ruined,

sitting here in this dumpster.

This poem takes just a little puzzling out, and then becomes metaphorical, and then personal. We ask, at first, Who is speaking here? And then, How might a human be used as a mask? And, finally, Have I harmed someone so that I might be better hidden? The poem also demonstrates Dorney's tendency toward a showy ending. Even so, the speaker's Erin/Shia/paper bag "I" gathers, as we read on, an intriguing, Whitmanesque depth. Every few pages Dorney writes another identity into the "I," an identity that might be arrogant, or enraptured, or merely observant. In "Song of Myself," Whitman writes, "You should have been with us that day round the chowder-kettle." Dorney uses LaBeouf's language to put us together around it.

I bring up Whitman also because of Dorney's interest in gender and sexuality. Whereas Whitman writes unabashedly about male eroticism, Dorney renders sexuality completely unremarkable. The female poet half-creates, half-discovers a male persona, and through him writes poems in which sometimes male, sometimes female speakers desire sometimes male, sometimes female bodies. In a book where speaking from a voice other than your own is the whole point, Dorney seems to suggest, Yes! This is my voice! And this is, too!

In the poem "Blessed," a sweet, awed, enthusiastic speaker, who identifies herself as "just a woman," is grateful after having been treated with gratitude by what seem to be fellow artists who, importantly, are men. The candid, energetic voice is pitched exactly right.

Those men are

incredible!

incredible!

incredible!

They creatively inspired me,

made me want to move forward,

treated me with respect

and gratitude.

I'm blessed,

I fell in love—

a pleasure,

and me

just a woman!

A little later, the poem "Sexy Sexy" is in the voice of a somewhat rough-edged, adoring, jilted partner:

sexy sexy sexy sexy sexy sexy sexy sexier sexy sexy

OR

She was raised on cowboy films

– the baseline stuff—

chased that gold rush,

fought for an echo,

beat me up so bad.

The poems I particularly love in this collection are, like "Sexy Sexy," more experimental in form. I love knowing that Dorney went through an interview and took all the different variations of "sexy" for a poem, and then titled it, "Sexy Sexy." Doing so makes erasure feel more like collaboration than appropriation, like Dorney's watching her source, and taking notes, and reacting to him. What kind of person could be so hot as to warrant the use of ten "sexys"? Dorney conjures her. Dorney uses this strategy, in which she points out specific words or phrases, highlighting LaBeouf's language, working with it in addition to erasing and recontextualizing it, elsewhere. In the poem "I Grew," she collects some of LaBeouf's subject-verb pairs:

I related

I used

I met

I would

I wanted

I knew

I looked

I decided

I could

I told

I got

I was so in love

I needed

I don't know

I can't

I have

I did

I've got

immaculate cheekbones

In all but three of these phrases, the object is invisible, an expanse of white space. The statements seem to report what happened, something that is definite and beyond questioning, and then puts this information right up against an absence. "I did tell them something, but what was it?" and, "What could I have done?" The past tense— I'm not sure why Dorney included the present tense in a few of these— makes the poem seem to be an elegy, or at least a memory of a former self. What can we know about the past? I was so in love. How do I console myself about who I am now? With something completely certain— my perfect cheekbones.

I Am Not Famous Anymore is Dorney's debut poetry collection. It's funny, sweet, and you don't have to read one interview with Shia LaBeouf to enjoy it.