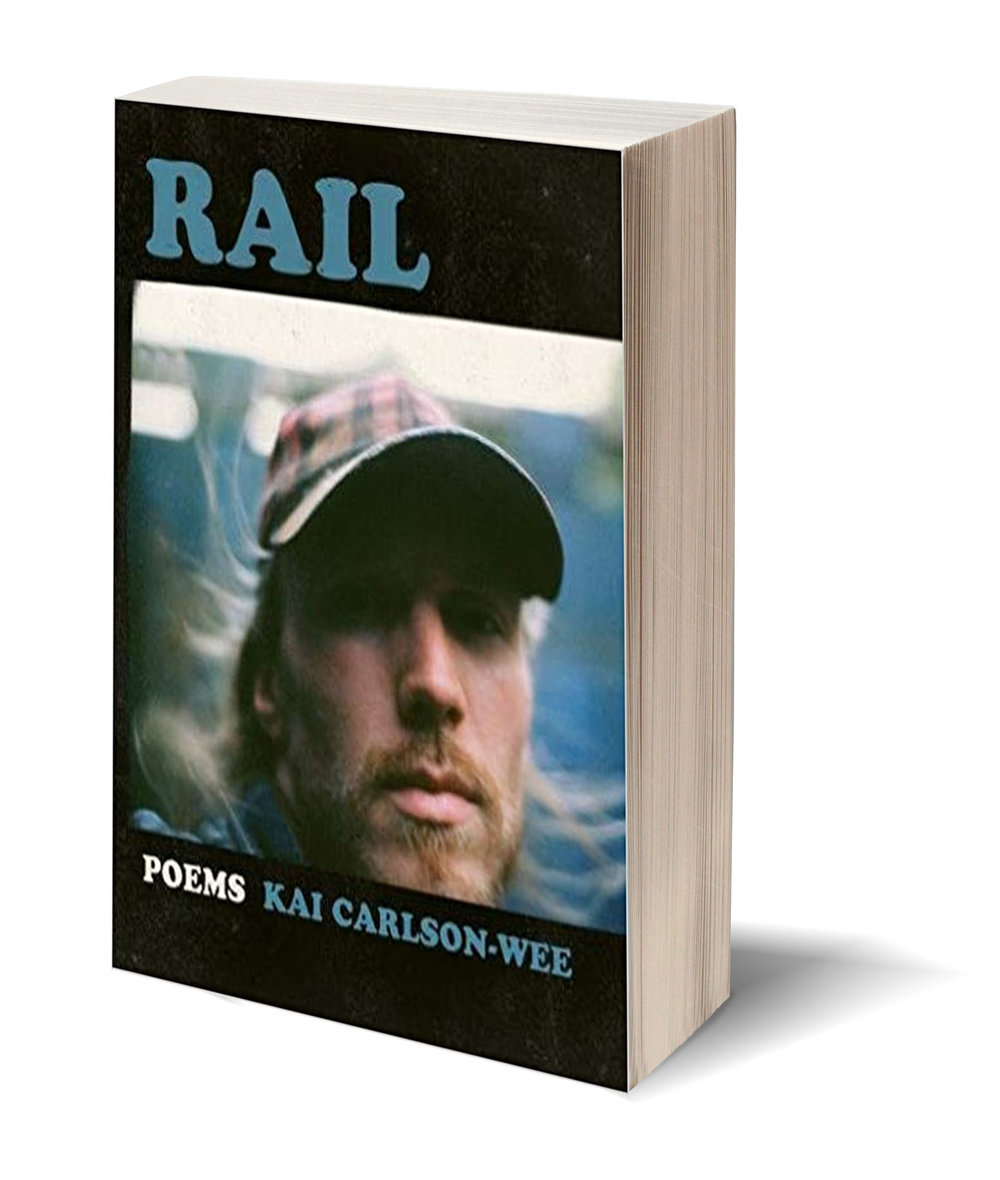

RailBy Kai Carlson-Wee

BOA Editions |

|

|---|

Reviewed by David Nilsen

What home

are we leaving? What distances blur

the electric fence? What hundred low thundering

wheels of darkness are coming to carry us

there?

These lines from the title poem of Kai Carlson-Wee's new poetry collection Railoffer the book's central questions and provide its driving visual motif. What does homemean when you're living off what you carry on your back, and what's carrying you is a freight train? What does all this land covered inside the belly of an empty train car mean in the context of a young life, lost and lonely and depressed, but alive and searching? What is sought?

Given the symbolism of train-hopping in American culture, most works of fiction, memoir, or poetry that include this method of travel tend to paint it as a means of freedom, discovery, and countercultural expression. In Rail, Carlson-Wee has a hard enough time keeping himself moving forward each day in a state of crushing depression to worry about what his travels might mean, though. He's not trying to stick it to the man or fulfill some American imperative of personal freedom; he's trying to survive. He writes in "Mental Health":

You count the weight of every

breath. You know it can't go on like this. But here you

are. This is life. This is the way your day begins.

Despite the effort needed to put one foot in front of the other in a state of despair and uncertainty, Carlson-Wee does find moments to reflect on his journey across the West on the rolling steel wheels of freight trains. "The train / is my shepherd," he reflects in "Where the Feeling Deserts Us," and he goes on to explain in the same poem why riding the rails in his state of confusion is an appealing thing to do:

This is the best

I can give you for a reason—the metal accepts you,

whoever you are. The train you are riding will only

go forward. The straight line is perfectly clear.

That straight line and clear destination is contrasted with the meaningless noise and disorienting haze of suburban American life. As he writes in "Depression":

my friends are asleep

in their anticipated lives, dreaming in the vain styles

of their age, painting their childhoods

over their eyes

In "Jesse James Days," one of Rail's most significant poems, he looks at this possible fate in his own life and in the life of his brother, a recurring character in the book:

What grainy, impossible dreams

used to guide us? What wildernesses burned on the vacated stages

and bankrupt resorts of our brains?

Anders, we get old. We divide ourselves up into seasons,

digressions, failed attractions, glorified versions

of jaded and lost men we promised

to never become.

Beneath the thick cloud of depression, and within the empty pursuits of late capitalism, the tangible solidity of the train—its predictability and pragmatism, its incontrovertible physics –provides something for Carlson-Wee to anchor himself to as it rumbles across the prairie. As he writes in "After Havre":

You can feel it going before it goes. Shivers along the connections, revived

by the engines. Five of them, suddenly pressing

their weight to the backline. Cracking along

the imaginary spine as my own bucket lurches,

and rattles toward Portland.

The immeasurable weight of the trains is referenced often in these poems, evoking the weight of depression but also the inevitability of movement, the momentum of aging, the sensation of being carried forward with or against one's will. Railcould nearly be summarized by these two lines from "American Freight," an extended poem that forms the spiritual center of the collection: "The weight of it. All of it. / Rolling away from its origin."

While it would be difficult to say Carlson-Wee heals from his depression in Rail, he does perhaps gain perspective on it, and on the dysphoria of being a soul and a mind inside a body in a materialistic era. Paradoxically, it is the body that offers that perspective—the body moved and altered by industry and labor, the body sanctified by the very rot that renders it perishable. As he writes in "Holes in the Mountain":

The scars on our hands are only around

to remind us: don't grow old in yourself,

don't get lost in this scrimmage

Kai Carlson-Wee is himself no lighter for having ridden the weight of a freight train, but those days and nights rolling on the broken backs of America's rustiest metaphor for its own failed dreams perhaps allows him to release himself, however briefly, from the spiritual consequences of mortality. As Carlson-Wee puts it in the collection's final lines:

And although the soul is a joke we tell

to the part of ourselves we can touch,

it's only because the soul is a fire, and laughs

at our sorrow, and has already survived us.