Reviewed by Rick Henry

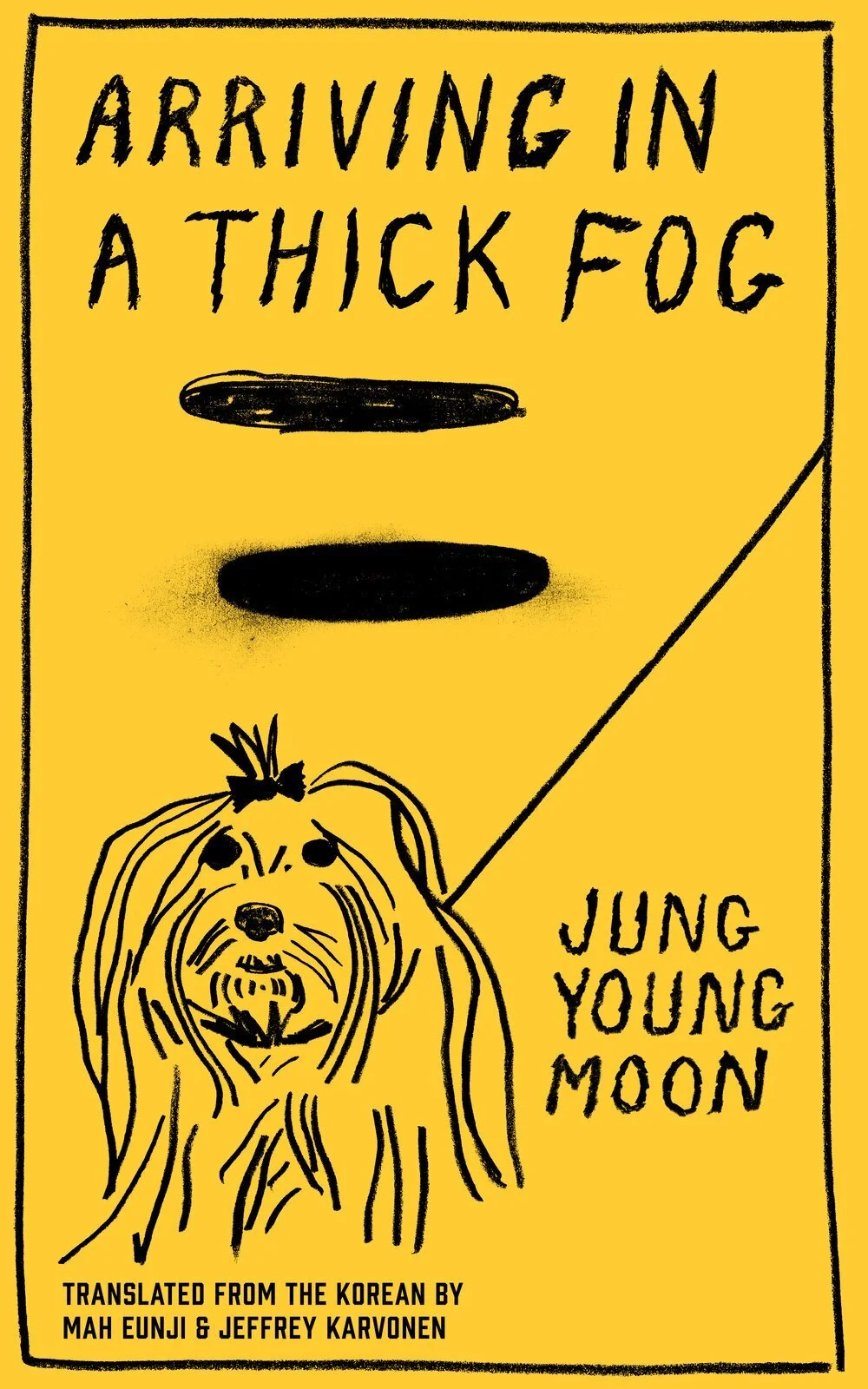

Jung Young Moon's Arriving in a Thick Fog might best be or not be approached as a continuation of the loose wanderings of a mind returning to many of the same topics and images he teases in his earlier books. As such, his is a long-term singular project much in the vein of Proust's Remembrance of Things Past (but in the ever present and therefore without nostalgia), or, as he tells us, under the influence of Beckett or Kafka or Woolf. Jung's work is in cascading arrays of details and moments, which are driven neither by plot nor by character. The people themselves appear with as much significance as do chestnuts or poodles or hats or nipples or dogs and dogs and more dogs.

We might clear the table at the outset. In 2017, when Jung published Arriving in a Thick Fog in South Korea, Justine Ludwig interviewed him for Korean Literature Now, an interview aptly titled "Writing for Skeptics: Navigating Meaninglessness." In response to many of the excellent questions, Jung offers what amounts to a manifesto, one worth attending to as an entry into his work—announcing nothingness, word play, meaningless, language games, anti-narrative, and the ordinary, mundane existences we live.

It shouldn't be a surprise given those positions that neither Arriving in a Thick Fog nor any of his other works are worth framing in ways formalized in traditional genres, characters, conflicts, drama, or analogous sets of constraints guiding the lyric or poetic.

With the publication of the English translation, points need repeating. Neither Arriving in a Thick Fog nor much of Jung Young Moon's work is a novel or short story or narrative wherein we are concerned with plot, or even what we might consider to be sequences of events that are motivated. Neither are his works character studies wherein it is interesting or relevant to have discussions about characters, their problems, needs, wants, satisfactions, or psychologies. Reading strategies and conversations would be better directed toward sequences of events which may or may not be happening and may or may not have importance to the sequences in which they occur.

What's left is in asking the reader to pay attention to what we ordinarily wouldn't pay attention to, and in contexts that are just as ordinary and, indeed, arbitrary (as in unimportant). This forces us to recognize that the entire business is undermined by the very act of writing, of selecting and assembling words and phrases, especially given that their referential functions remain intact, even if what is represented might be stripped of its dramatic possibilities.

Perhaps a taste of his attention might be useful. The first of the four extended non-narratives in this collection is entitled "Dog Ear." In its opening twenty pages, it is abundantly clear that the "I" is existentially static. "I" simply engages a long series of topics even as the first five pages are primarily given over to the folding and unfolding of a dog's ear. The setting is the dog owner's place. "I"'s actions involve the folding/unfolding. His mind lands on (in this order) aprons, war, alcohol, authors/readings, Poincare, language games (including tongue twisters like "the quick brown fox . . ."), flowers, a thin shirt worn by the owner, her nipples. The owner of the dog provides the action: she leaves to take a shower, comes out of the bathroom, blow dries her hair, goes to the kitchen, chops, returns and tells him to leave. The emotions are hers but simply stated, not described: anger, surprise. His momentous thought? He considers, however briefly, kidnapping the dog. He leaves but the sequences of topics continue in a series of one-paragraph events, a seemingly random set of associations: weeds, the female pelvis, a young woman with a nose job, drinking tea, ants and the First Supper. And so on.

Undermining this attention to the mundane are two looming comments in the collection: "My inability to be serious about anything at all was a chronic issue, and one of the biggest challenges in my life"; and reflecting upon his most recent moment, "the life I had lived until that moment . . . felt terribly insignificant." Also undermining the basic premise of representing the mundane is not so much the ever-present is/is not or the conditional state of affairs, but a questioning of a slightly more significant nature.

But games are successfully played throughout. Jung's word games are stripped of extended metaphors, replaced by (simple?!) juxtaposition. The juxtapositions are often among representations or propositional content. Much of the goal is to see how long one can write about something until its meaninglessness is exhausted, while (perhaps) still maintaining a reader's interest. The bottom line lands not on meaning (where meaning is based upon narratives of cause and effects, etc.), but to be interesting enough to move on to the next sentence even as the entire project is a documentation of 'mere' existence. An individual existence consisting of threaded impressions and events.

The biggest issue for the extended bits of prose in Arriving in a Thick Fog and with the majority of Jung's work is translation. How do these games survive the movement from Korean to other languages? How does the series of drinking tea, ants and the First Supper survive the move from Seoul to Fort Worth?

At the risk of violating everything near and dear to Jung's work, I offer a metaphor. Perhaps Jung's work might best be approached as one would an amusement park ride. One pays one's money to move from one slow-motion linguistic tilt and whirl to the next.