Reviewed by Philip Probasco

Devotees of John Brandon's work will not be surprised that his newest novel, Ivory Shoals, begins with a crime. It's a relatively minor theft, not the violent, destabilizing event it is in his 2010 novel, Citrus County, and it turns out to be unimportant to the story that unfolds. Ivory Shoals is not the tale of an outlaw—it is rather the tale of adolescence, of growing up, pursuit of independence and responsibility. It is, in other words, the tale of a pilgrim.

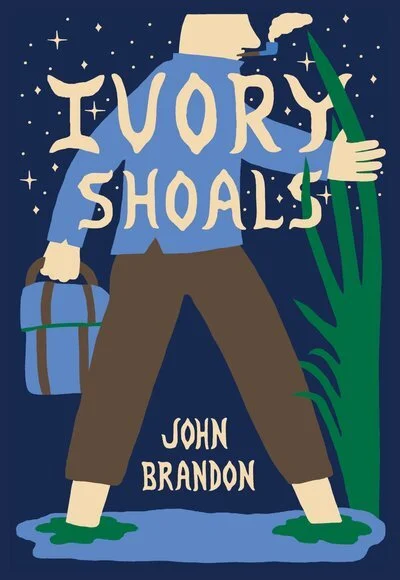

The South has just surrendered, and 12-year-old Gussie Dwyer (our pilgrim) has lost his mother, whom he loved: "the woman who'd cared for and fed and tutored him all his days." Now untethered to his hometown, Gussie helps himself to a few bills from the local bar till, packs some provisions—including his trusty tobacco pipe and his father's golden Waltham pocket watch—and books it out of town. He aims to make it to his father's estate, Ivory Shoals, return the timepiece, and "be called son" just one time.

As Gussie swats and mucks his way across the panhandle, hopping trains and sleeping in busted wagons, he encounters kindly and unkindly folk, some offering food and shelter, and others the end of a rapier or revolver. Raised by his intelligent, golden-hearted mother (a sex worker by profession), Gussie navigates perils with resourcefulness, pluck, and a smart tongue to make Mattie Ross proud.

And yet, hot on Gussie's busted heels, soon to test his grit and faith, are two antagonists. One is a ruthless bounty hunter, a postbellum Anton Chigurh by the name of August, whose bonafides include catching runaway slaves and once drowning seven kittens with his bare hands. Two is Julius, the debaucherous heir to Ivory Shoals and more of a dandy menace (in his formative years he opted to kill poor critters with a slingshot) who now plots how to clean-handedly dispatch this rival for his inheritance.

What separates Brandon from a certain southern Gothic Tennessean he's often compared to is the extra dimensions he gives his vilest characters. August and Julius refuse to sit still within the villainous type the story casts them in: they can be at times charming and vulnerable (and stellar tippers to boot). They don't feel molded by an author so much as by the story world, and part of the reading pleasure is anticipating the next way they will surprise. Take for instance the kindness Julius shows his father's servant Abraham, who spends the book puttering around the grounds of the estate, fretting over the coming confrontation. When it comes, when Gussie and Julius arrive (at the same time, in a Gothic bit of staging), it's not the empty yeehaw you might expect of another novelist. Enriched by deep characterization and bleached of glamor (readers of Arkansas and Citrus County will again be unsurprised) it tells us something about the characters.

But for most of its length Ivory Shoals is a road novel. It's a story of geography, vegetation, wildlife, and food and people. When one finishes, one most remembers the vivid kaleidoscope of the passing landscape, both natural and settled. In all the motion, ideas and emotion quietly fall into subtext; the main event is the magnolia blooms and melon slices, the oil lamps and cheap cigars. Gussie's grief is contained within this splendid, alien landscape, the ash trees with "their blanched flowers like burst stars," the "woods marbled with luminous wards of scarlet-budding milkweed."

But occasionally, very occasionally, Gussie does take the time to meditate on his journey and his loss, and the book reaches beautiful crescendos at the point where it pulls its focus from the next flower and lifts to take in the whole tract of woods:

He passed behind a series of defiled manors, each spookier than the next, windows shattered and doors wagged open, gardens horse-cropped, porches adorned hundred-count with brown bottles. These wealthy families had fled farther inland, or some of them, Gussie had heard, straight north, right up clear to Virginia, the belly of the beast, where at least there might be an army to defend them. They'd lost what they'd lost. Gussie had lost what he'd lost. Others had had nothing to lose to begin with. None of it was fair or unfair. They just had to keep going. Everyone. They had to keep going toward whatever there was.