Reviewed by Rick Henry

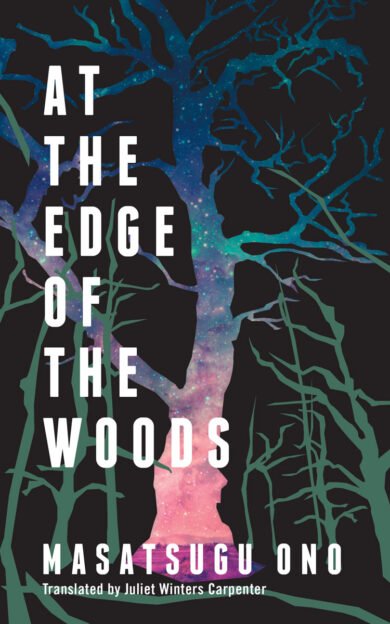

Masatsugu Ono is slowly gaining the recognition he deserves in the United States. He is an important Japanese writer, winner of the Ashahi Award, the Mishima Prize, and the most prestigious Akutagawa Prize. At the Edge of the Woods is his third novel appearing in English, after Echo on the Bay and Lion Cross Point. Dominant issues in these novels: small, isolated communities, a family suffering trauma, the importance of place both as a setting and as a character, and an essential engagement with the outsider, however broadly defined that otherness might be. All of these issues play out in an ominous, sinister, dissociative world of the fantastic, fabulous, and fairy tale-eqsue, all sliding toward magic realism for the simple fact that what is extraordinary or remarkable quickly becomes normal.

At the Edge of the Woods consists of four interlocking narratives that open with a family moving into an isolated house on the edge of a woods. The story is narrated by the father. The mother is pregnant with their second child and leaves for her parents' home to have her child. The son is young, perhaps four years old. The woods? They are the source of many of the outsiders and much that is strange. We might say the same of the pregnancy.

The first narrative is entitled "A Breast." Having moved into its new home, the family is quickly presented with a host of sounds emanating from the woods–sounds that saturate the atmosphere and intermingle with their talk, the radio, and the TV. By paragraph three, the father and young son are joined for their walks in the woods by a copse of trees that pass them, wiggle their hips, huddle, whisper, and fill the woods with their very presence and, as the father says, fills their "gaps in consciousness." As if those gaps weren't full enough, loneliness and desolation overwhelm everything.

What drives the novel is how Ono's imagination floods the gaps in consciousness. He is doing precisely the opposite of what Viktor Schlovsky sees as the function of art: "to make the familiar strange so that it can be freshly perceived." Ono gives us the strange–that which is the outsider–so that it, too, might be freshly perceived.

Once the woods have been firmly established as a sinister world of imps and dwarfs and other oddities, Ono presents us with our first major theme. A nearly apparitional old woman appears out of the woods, hand in hand with the boy, wearing an open robe with a breast exposed. The son "adopts" her as his grandmother. Against the background of coughs coming from the woods, she tells the story of her child's conception. She confesses that when she was the boy's age, she wanted a penis, thinking her mother could go buy one at the store. She has little control of her body. She soils herself. The father sets her up in the tub, washes her robe, and goes off to purchase adult diapers. When he returns, the grandmother is gone. The boy has no recall of her. The house has been cleaned. He's been talking to his mother on the phone. What is most remarkable is how quickly the father moves to take care of the old woman, who was clearly dangerous but who also becomes an opportunity for the father to act humanely. The house has been cleaned. But the eeriness remains.

The old woman's story repeats through all four sections of the novel with variations. In the second section, which is dominated by its own integrated and overlapping stories, we find the pregnant mother traveling to her parents. When she disembarks from the train, she spies a near-dead woman and newborn. Our mother offers her breast. It is tempting to place the newborn as the outsider, as the strange, as that which fills the gaps of the conscious, as that which has become recognizable.

There is some resistance to the revelation of humanity. The second and third narratives, "The Old Leather Bag" and "The Dozing Gnarl," are the most sinister, the ones where loneliness and desolation come to the fore. Amidst a host of seemingly otherworldly situations, we see long lines of refugees walking overburdened with their own possessions. To the symphony of sounds coming from the woods, his son adds whimpering and retching. There is a dead pregnant woman discovered in the woods. Animals are beaten and killed. For these moments, there are no kindnesses, no responses. The best that can happen is that they are documented.

"Nothing I might encounter at the edge of the woods could surprise me anymore." So opens the fourth narrative, "The Cake Shop in the Woods." We might see why. Ono is clearly versed in Western classical music. References to specific composers abound. But it also offers another way into his work, into how he structures his novels like classical productions relying on theme and variation. The joy and surprise in his novels come from such play, such variations and how they are juxtaposed against and absorb that which is outside the norm, on the other side of the edges. At the Edge of the Woods is an excellent introduction to his work.