Reviewed by Abby Walthausen

In his recent "biographical novel" of Louise Bourgeois, Jean Frémon writes of the experiment that "Any written portrait, unless it's imaginary, must be made of memory: there's no model striking a pose, motionless, before the writer." And while this might be true for Frémon, who drew on his longtime friendship with the artist to create a poetic approximation of her voice, Nicole Rudick's recent experiment with biographic form faces no such obstacle. Rudick's assemblage is based not on memory, but on the poses that artist Niki de Saint Phalle spent a lifetime striking in her journals, letters, notes, and text-heavy works on paper. Best known for her large public works, like Paris' Stravinsky Fountain and Tuscany's Tarot Gardens, Saint Phalle was also prolific in the more intimate space of the paper works where she developed her ideas for art and self while also setting the tone in which her story might be told.

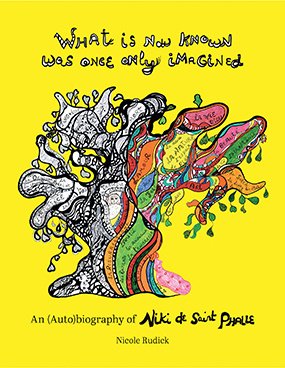

In What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined, Rudick picks up where Niki de Saint Phalle left off in her own attempts at autobiography. Rudick uses excerpts from two memoirs of Saint Phalle's life: Traces, which focuses on the traumas of her childhood, and Harry and Me, which recounts her early family life with poet Harry Matthews. At first glance, Rudick's book seems like a simple repackaging and expansion of the two, but it distinguishes itself by both its omissions and its additions. First off, Rudick's book dispenses with photographs of any sort—none of the artist, who was known for her model's appearance, and who acknowledges the fact that much of her early notoriety was owed to it. There are also no photos of her best-known works, much of which is sculptural, tactile, performative, interactive, and mechanical. Since everything is work on paper, some "lousy little scribbles as well as finished art," in the words of the artist, echoed by Rudick, the book narrates from a vantage point of genesis rather than retrospective.

This book is purely text and image, ink and marker, which makes for a wonderful space to see Saint Phalle's pervasive tendency to inflate in both figurative and literal ways—she writes positively always, with a penchant for fantasy and maxim (in fact, the book is titled from one of William Blake's "Proverbs of Hell"). When she describes breaking with her first husband as a flower that has bloomed and withered, she writes and draws "I took the petals and put them in a box and I locked the box in my heart." She compliments every artist she mentions, a rare thing for the art world, speaking about the way their suggestions, their feedback, and the mental "ping pong" she played with them always inspired her to go forward. From her first scratches at an idea, it is clear that she is reaching for collaboration, for work that lives socially in the world. And there is the fact that she could not draw depth. Perspective proved impossible for her, and, in order to bring to life the emblems that haunted her—from monsters and serpents to joyful female "Nanas"—she sought freedom from the page altogether. For the giant sculptures that would become her signature, she needed other artists, artisans, patrons. Throughout her career, she called on teams to add great dimensions to her vision, essentially becoming a foreman to huge installations, sculptures, gardens.

What Rudick adds to the biographical project is a myriad of gems from the Saint Phalle archive, which now resides in La Jolla, California. There are roughly sketched proposals of installations, letters, fake letters, lists, lists turned into finished drawings. Saint Phalle's favorite images recur again and again, in her familiar vulnerable and meandering draftsmanship. She fills the page with gratuitous labels that sometimes read as a conscious naivété and sometimes like a pure lack of confidence. Rudick gives "syntax" to the pieces she includes, making "meaning through their contiguity . . . each work a word in a sentence, a sentence in a paragraph, and so on." For example, in one incredible run of pages, Rudick poetically elides Saint Phalle's transition from her performative, violent, "Tirs" or shooting paintings, in which she would symbolically kill her abusive father, to her feminine, cycladic, joyful "Nana" sculptures. She does this by juxtaposing drafts, drawings, and letters about the shooting paintings with some words about rootlessness, and follows them with an annotated poster for "Hon" Saint Phalle's cavernous, pregnant female form. It seems almost a map for following the Virginia Wolf dictum that "it is fatal for a woman to lay the least stress on any grievance . . . for anything written with that conscious bias ceases to be fertilized." Saint Phalle's annotations have visitors entering her installation through "THE BIGEST [sic] AND BEST CUNT IN THE WORLD," to find inside a milk bar, an aquarium—spaces of wonder and hilarity—and little room for grievance.

In another moment of expertly placed "syntax," Rudick reproduces in full a pamphlet that Saint Phalle was commissioned to make about AIDS, which includes a playfully drawn list of what you can't catch the disease from (a canary, combs, a doorknob) and ends in a page devoted to the words "the worst part of all serious disease is the anxiety it causes in those who are sick and to those who love them. WE MUST OVERCOME OUR FEAR." A few pages later, we find letters and images mourning the death of Jean Tinguely, kinetic artist and her longtime lover and collaborator. Snuck in between these documents of mortality, Rudick includes hastily written diary pages about Saint Phalle's lifelong love of birds, "Immortal birds. Sad birds. Triumphant Birds." The arrangement of these different registers vibrates against shared themes, and Rudick nudges forth a three-dimensional picture of how the artist processes grief.

On a grouchy day, I find Saint Phalle's work, drawings in particular, annoying to look at—Tinguely's as well. Despite being important 60's artists, there is something about each of the pair's wildly incongruous styles that left its residue in the 90's, the afterlife of Tinguely's work being Nine Inch Nails videos, and that of Saint Phalle's being the aggressive, clashing joy of the Red Hat Society. But like all complicated art, I am also in awe of it, and the pop associations I have with it prove little but the pair's pervasive reach. Moreover, it makes me question the taboo of whimsy, and I understand Saint Phalle's instinct when she left her darker work behind–that unmitigated joy is sometimes the most shocking of all.

In one of my favorite journal entries from the 20-year period when Saint Phalle was building her Tarot Garden, she describes a "laughing therapy" she undergoes for her rheumatoid arthritis, in which she watches old comedies, willing raucous physical laughter to heal her pain. Its efficacy is mixed, but real alchemy for her seems to be the many, many angles from which she is able to perceive herself anew: friends come over to laugh with her, her granddaughter feels her newly firmed up stomach muscles, she considers whether this practice makes her more fundamentally American or French, and, finally, she wonders if the locals surrounding the Tarot Garden now have an even firmer impression that the women constructing monsters is truly a witch. She strikes a pose, she puts on a performance. She bridges the gap between the reclusive "outsider" artists whom she considered spiritual brethren—Simon Rodia, Facteur Cheval—and the well-connected, intercontinental, cosmopolitan artist she was. In this volume, Rudick shows us how Saint Phalle's writing is as social as her life and her work—all about accessibility, inclusivity, and consensus. But in these three things rarely associated with modern art, she invented her own vocabulary of transgressive beauty.