Reviewed by Abigail Oswald

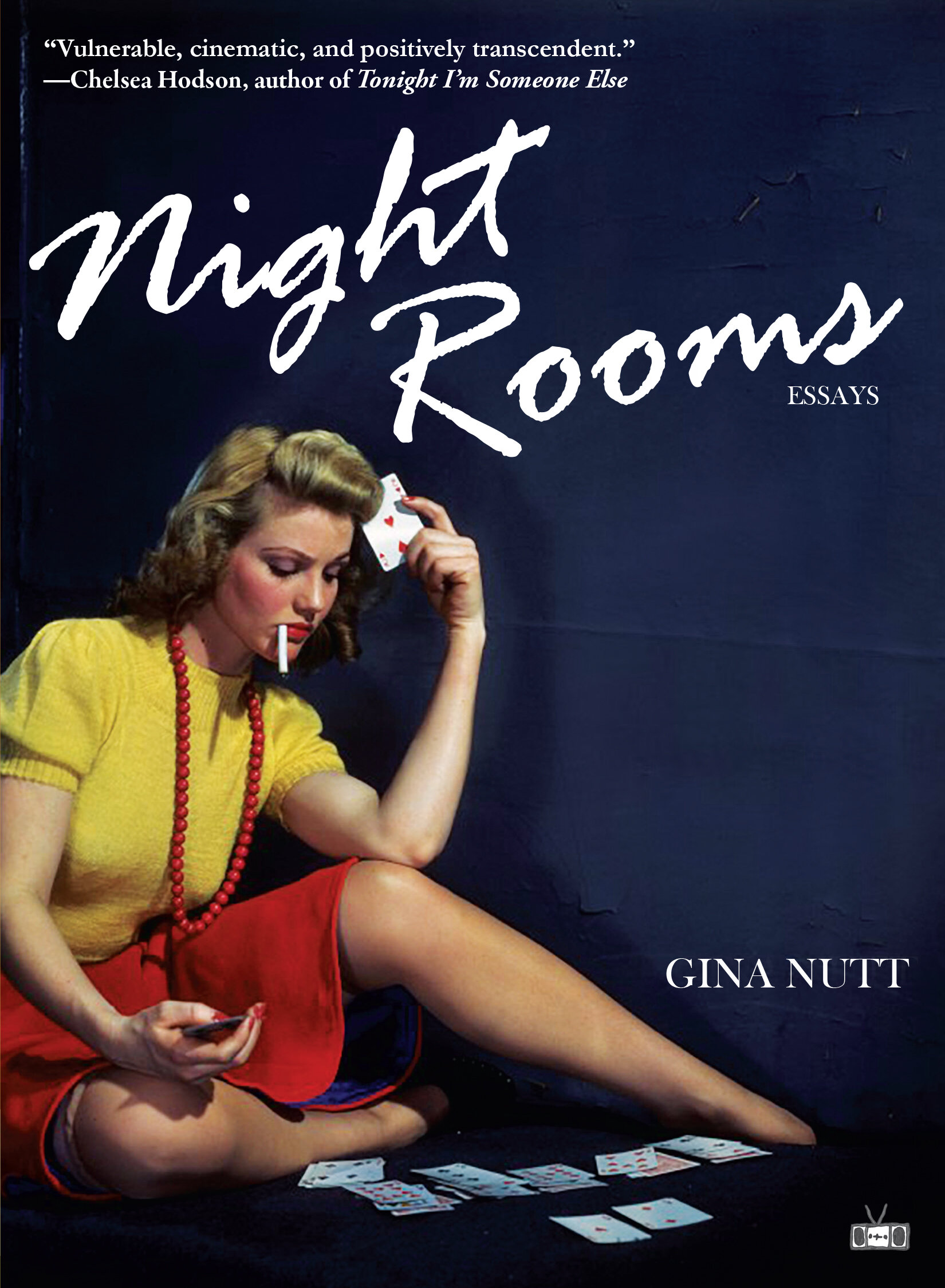

I have a memory of watching Jaws as a child. Before I probe for specifics, the experience exists in my mind as image and sensation: the square television beaming blue light, the whir of a VHS tape's rewind, dusty sunlight streaking through tiny basement windows. But the initial childhood joy of watching a movie—any movie—is quickly darkened by the depicted events themselves: a red cloud of blood in water, the scream of a girl who was not written for survival. The memory devolves finally into the abstract—fear and light, both recurring themes in Gina Nutt's transfixing new essay collection, Night Rooms.

One of the most interesting through lines of Nutt's craft is the defamiliarization that occurs within the text. Movies are frequently mentioned by name, but, in other cases, they are stripped of their proper nouns and referenced solely by a central character or notable scene—plucked from their context, denoted by just the right details, and woven between memories of Nutt's own adolescence or adulthood. Freddy Krueger becomes "the nightmare man." Titanic is name-checked in one essay and later identified by the "staggered intervals" of its submersion in another. One of the most memorable scenes in The Shining is vividly drawn as "A man approaches a beautiful woman in a mint-green bathtub in a vast, old hotel." I have only to read the sentence "A ghost girl haunts her audience" to conjure The Ring's unforgettable Samara in my mind's eye as she peers out of the television from behind her dark curtain of hair.

It's a technique that effectively imitates the fallible workings of memory—sometimes we might fumble a character's name or long-forgotten title only to come up with a single, haunting scene in its place. (Though her name escaped me all these years, I will never forget the sound of the Jaws girl's scream.) On a craft level, such choices speak to the heart of what horror is: the primal, nameless feelings that remain with us long after the credits roll. The reader in turn is forced to take a more active role in what they're reading, as they must fill in the gaps themselves (or, conversely, search for the answer in the blessedly exhaustive Works Referenced at the back of the book). Thus, every reader's experience will be a little different depending on personal viewing history, certain lines triggering instant recognition or a vague but gnawing familiarity—like when you recognize a certain actress but can't quite recall her name.

Nutt's writing often imitates scene—fleeting glimpses that weave in and out of ages and eras, often beginning with an evocative image on which the reader can fixate. Each essay feels akin to a half-remembered dream, drifting with a seemingly effortless free association that lends the collection equally to rapid, bingeable consumption or a slow, savored reading. (My experience was the former.) The language is beautifully recursive, looping back to layer new thoughts onto earlier ideas and images, offering the reader a little spark of pleasure when an independent connection is made while reading—and not just within single pieces, but across different essays as well. The collection paints a cohesive portrait stroke by stroke, coalescing into a whole once you reach the final page.

Much of Night Rooms is about the primal and near-inexpressible; Nutt grapples with Big Things: anxiety, fear, depression, suicide. As the essays are unnamed, I jot down the feelings and images I am left with in the space following each final paragraph, scrambling to grasp the "aboutness" of each one as I sometimes do when the screen fades to black following the last scene of a particularly good movie: memory, grief, pageant, house, darkness, light, dread, ballet, birth, blood, scars, flesh, hunger, loss, fog, identity, safety, zombies, legacy, souls, storms, memory, solitude, and so on. Each essay stands on its own but also functions as a building block within the collection's overarching themes—which, even considering the frequent heaviness of the content, are more hopeful than you might think.

If there is a single theme that links all of the essays in Night Rooms together, it is survival. The first essay introduces the thread of the "final girl," historically exemplified by characters like Alien's Ellen Ripley and Scream's Sidney Prescott. In short: she goes through hell but comes out alive on the other side. Nutt's ruminations on past trauma place her firmly in this camp as she grapples with her own monster: "I'm trying to stare down despair and tell it, I have lived with you for many years and I plan to live alongside you for many more." So much of talking about horror, after all, can end up being a conversation about life itself.

Night Rooms enters into the canon of books that exist as a web as opposed to an isolated point—books that spark a list of items you wish to return to or seek out anew. Nutt's references flow seamlessly and speak to another undeniable joy of movies: the nostalgia assignments they spawn, the gaps in your history you come to realize you should fill. Night Rooms will likely leave you with many trails to explore on your own, if you're brave.

I have seen and re-seen well over a thousand other movies since first witnessing that cloud of blood in blue water, but Jaws was never one of them. After I finish Night Rooms, I locate the film on a popular streaming platform—a far cry from the VHS tape of that original viewing—and steel myself accordingly.

It's not that my fears have changed significantly since I was younger. Sure, I'm not afraid of the dark anymore, but I'm still afraid of the unknown—and this, I've found, is what links the terrors of adolescence and adulthood. The shark attacks are frightening, but for me, true horror exists in the near-unbearable moments before, when you are wondering whether or not the monster will appear at all. When the only thing you know for sure is that you cannot trust your safety—this is horror. As Nutt herself says: "Sometimes the unseen is more terrifying than what's in view."