Reviewed by Keith Kopka

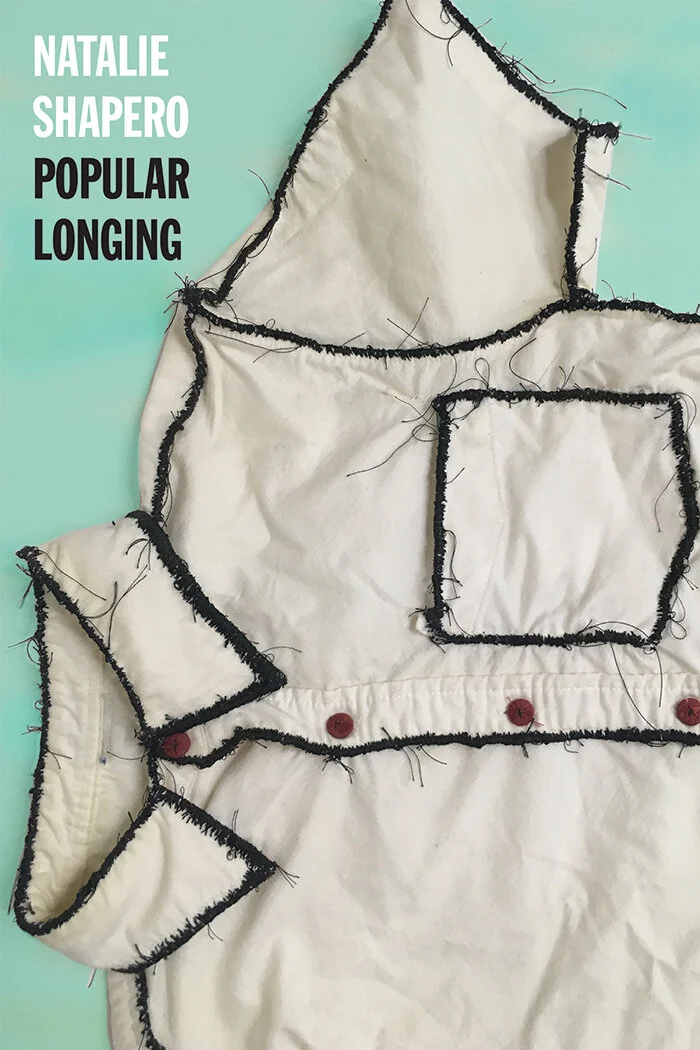

Popular Longing, Natalie Shapero's third collection from Copper Canyon Press, continues the tradition of Shapero's singular, and now signature, voice-driven style. The conceits, actions, and pacing of each poem are so well constructed that they could be chiseled from narrative stone, and Shapero's control of lineation and language allows readers to engage with the unique and sometimes darkly humorous logic of the world that her poems invite them to inhabit. Popular Longing finds Shapero taking on some of the darkest and most absurd elements of humanity with a stylistic bravado that never missteps and never misses its mark—her poems are works of craftsmanship at the highest level.

One of the most vital elements of Popular Longing is in Shapero's ability to engage her readers through observational lyric-narratives. Although many of the poems in the collection use the narrative "I," Shapero is able to draw readers into her poems in ways that are less narrow in approach than many of her contemporaries. While resisting the trappings of the confessional genre at every turn, the poems in Popular Longing still feel confessional because of Shapero's matter-of-fact tone and conversational language. However, as soon as recognizable elements of the first-person confessional begin to dominate the direction of a poem, Shapero takes a step back by shifting to another character or setting outside the speaker. In some instances, Shapero turns the poem's attention toward the reader through the use of the interrogative or an expertly placed "we" or "you." For example, in the poem "Fake Sick," Shapero opens the narrative in the third person before shifting to a more confessional "I" until ultimately turning the poem's lens back toward the reader. She writes:

The past is the same as anything else—we built it

And now we can't kill it. We keep lurchingat it with the scoring ax . . .

. . . I'm ready to stop remembering. The trouble is

there's nobody else who can do it. A memoryisn't a metal grille drawn down on a storefront . . .

. . . You can't fake sick, call in. There's no other person

to wake in the slate dawn, drive into downtown,

locate the recess, collapse the gate, maneuverthe thing out of view. There's only you.

This kind of expertly deployed shift in perspective allows readers to engage with Shapero's poems in ways that feel highly personal. In other instances, she uses her thorough understanding of narrative construction to present information in ways that make readers feel included as a poem's trajectory unfolds. Shapero constructs her lyric-narratives so that readers feel as though they are making personal discoveries alongside her speaker. This structure is uncommon. Many poems present information in ways that make readers feel like they have arrived "after the fact," that they are now being "let in on" a speaker's already fully formed thoughts and observations. There is an egalitarian nature to Shapero's voice, and it is a pleasurable experience to travel with Shapero as her logic unfolds. In "Weekend," she writes:

Some people despise doing laundry, but I don't

mind it, and I think we can all agree it feels so good

to engage in something you don't

mind. To have a neutral feeling. My only two childhood

memories are hearing the song EVERYBODY'S WORKING

FOR THE WEEKEND and seeing the bumper

sticker THE LABOR MOVEMENT: THE FOLKS WHO

BROUGHT YOU THE WEEKEND. I gathered

the weekend is the portion of life that is understood

to matter . . .

These kinds of unpretentious moments of discovery allow readers to more fully engage with the world that Shapero's poems inhabit. However, Shapero is not just concerned with the banal aspects of life. Through external violence in poems like "It Used to Be We had to Go to War" as well as in instances of more personal violence in poems like "Some Toxin," Popular Longing invites readers to engage with the subject of loss. However, Shapero often amplifies the complexity of this subject by setting it against the banality of contemporary capitalist existence. For example, in "Some Toxin," Shapero faces down mortality and isolation:

This is what we get. This is the penance

for extending and extending the human lifespan—

now some people live a hundred and twenty years . . .

. . . interviews about what keeps them ticking.

The secret is always some toxin like bacon or vodka,

and the joke that ensues is always the same: . . .. . . This is the penance. Back when even the powerful

died younger, they would lose one another and dutifully

wait to be reunited in Heaven. We wait for that

still, but now in the absence of Heaven. We say someday

we'll find each other, year after year on Earth.

In instances such as this, it might be tempting to say that Shapero is a poet who turns to humor, even black humor, to temper and explore the many complex subjects in her work. However, although there is humor within these poems, to say that Shapero is a poet who depends solely on humor in Popular Longing would be a discredit to the analytical thinking that is always at the forefront of these poems. Shapero's wit is certainly a part of her poetic intelligence, but it never takes center stage over the craft and thoughtfulness of her work.

Popular Longing, in the end, is a collection of poems that asks readers to take a hard look at their humanity. However, it is the wisdom that Shapero imparts through her unique and insightful voice that makes the poems in Popular Longing so memorable. Shapero is a poet who has crafted a truly singular voice, and, in this collection, it feels as though that voice has moved outward, beyond the self, towards a greater cultural interrogation that feels important enough to make one excitedly anticipate more of her work.